New York City Mayor Jimmy Walker (1881-1946) was commonly referred to as “Beau James” for his flamboyant lifestyle and his taste for fine clothes and Broadway showgirls.

Mayor Walker was also a product of the powerful Tammany Hall machine that traded in political favors and outright bribery. When he took office in 1926, the economy was riding high, and few seemed to care that hizzoner was aloof, partying into the night (while openly flouting Prohibition laws), and taking numerous pleasure trips to Europe. He easily won reelection in 1929, but when the stock market crashed later that year his hijinks began to wear a bit thin, and reform-minded politicians like State Senator Samuel H. Hofstadter began looking into corruption in New York City. The actual investigation was led by another reformer, Samuel Seabury. The New Yorker’s E.B. White looked in on the proceedings and its star witness, Mayor Walker.

Public opinion really started to turn on Walker with the death of star witness Vivian Gordon (see caption above). The final blow came from New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt, who like Walker was a Democrat but unlike Walker was not a Tammany product. Roosevelt was also running for president, and rightly seeing Walker as a liability, asked the mayor to resign, which he did on Sept. 1, 1932. That event was still three months away when E.B. White wrote these concluding lines:

Eight days after Walker resigned from office he caught a boat for Paris, where his mistress, Ziegfeld star and film actor Betty Compton (1904-1944), awaited him. They married the following year in Cannes.

* * *

Out of the Shadows

F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald were Jazz Age fixtures, cutting wide swaths through literary and society worlds filled with wild drinking and various infidelities. Francis Scott (1896-1940) was a chronicler of that age, most notably with The Great Gatsby, but Zelda (1900-1948) also took pen in hand, contributing short pieces to various magazines in the 1920s. By 1930 their self-destructive ways caught up with them both, and Zelda was admitted to a sanatorium in France that spring; it was the beginning of a long road of treatments that would end in her death nearly two decades later.

In 1932, during her stay at the Phipps Clinic (Johns Hopkins), Zelda experienced a burst of creativity, writing an entire autobiographical novel — Save Me the Waltz — in just six weeks. Sadly, it was not well-received (by critics or by her husband), and fewer than 1,400 copies of the novel were sold — a crushing blow to Zelda. However, during that same time she published a short story in The New Yorker titled “The Continental Angle.” Here it is:

* * *

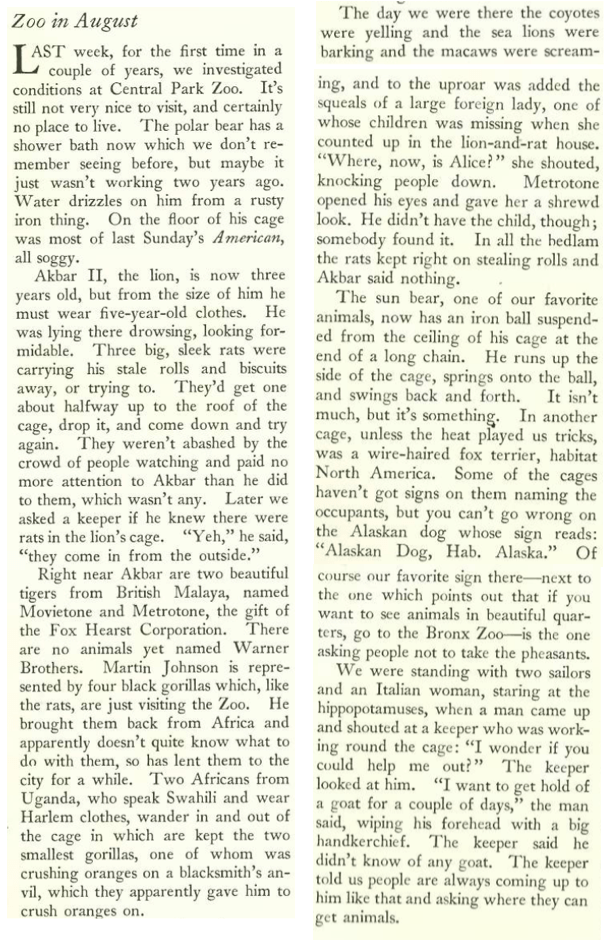

From Our Advertisers

Yet another stylish and very modern-looking ad from Cody, thanks to the artistry of American fashion illustrator Ruth Sigrid Grafstrom…

…while later on in the issue French illustrator Lyse Darcy gave his subject an Art Deco look to promote Guerlain’s face powder…

…Darcy was famed for his Guerlain ads from the 1920s to the 1950s…

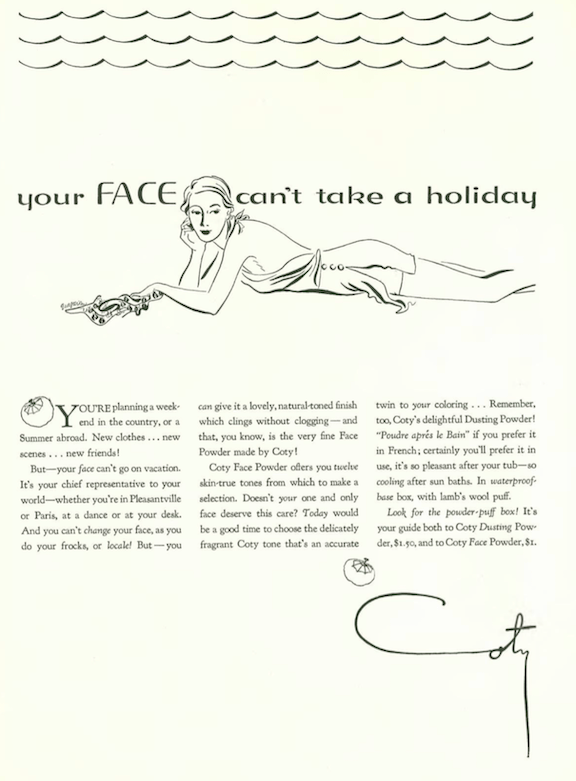

…Powers Reproduction turned to star power to promote their latest color engraving techniques…

…the actor Marguerite Churchill (1910-2000) had a film career spanning 1929 to 1952, and was John Wayne’s first leading lady in 1930’s The Big Trail…

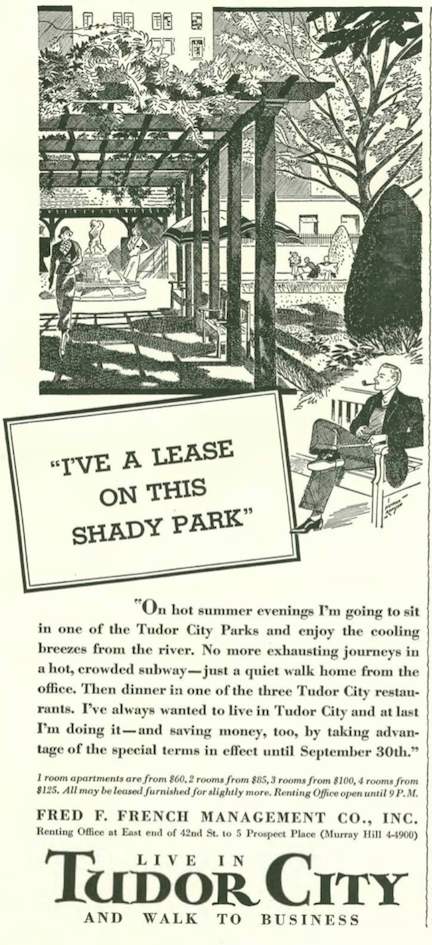

…and we head back to the city, Tudor City, to be precise, where apparently it was common in the 1930s to spot a gent in formalwear relaxing with his pipe…

…on to our cartoons, we have James Thurber contributing some spots…

…Rea Irvin continued to visit the world’s “Beauty Spots”…

…Garrett Price showed us a couple looking for the “We Want Beer” parade…

…which happened three weeks earlier, on May 14, 1932…the parade was organized by none other than Mayor Jimmy Walker, who believed prohibition was making life difficult for New Yorkers…

…Barbara Shermund introduced two men with bigger issues than beer on their minds…

…John Held Jr. continued to plumb the depths of the naughty Nineties…

…and some more naughtiness, courtesy Gardner Rea…

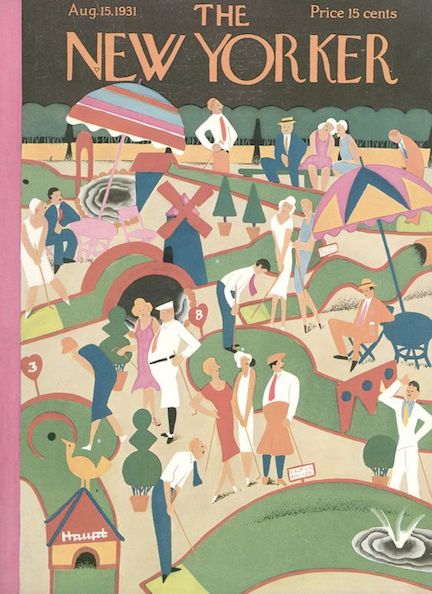

Next Time: Summer Indulgences…

“

“