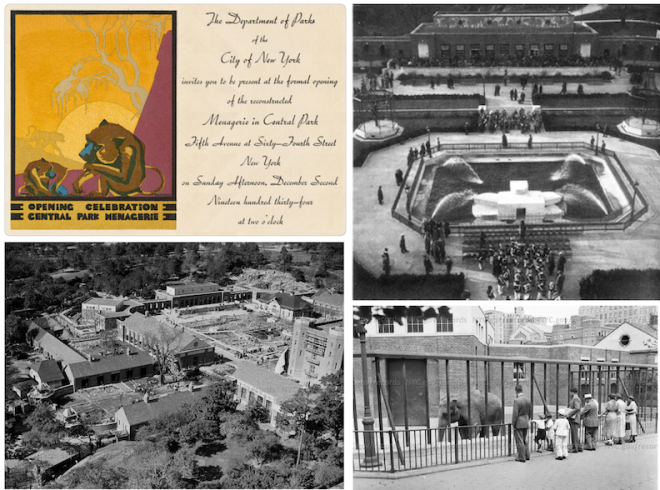

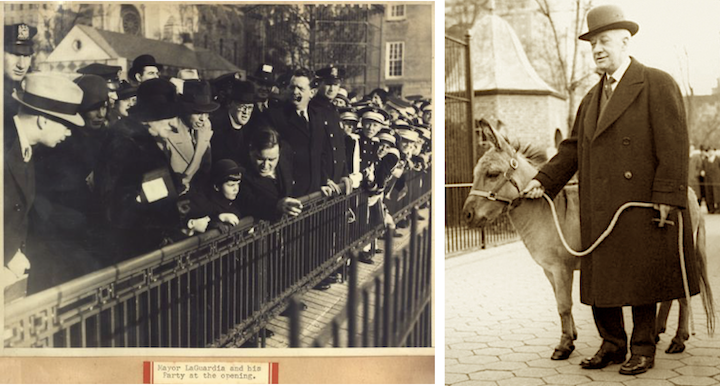

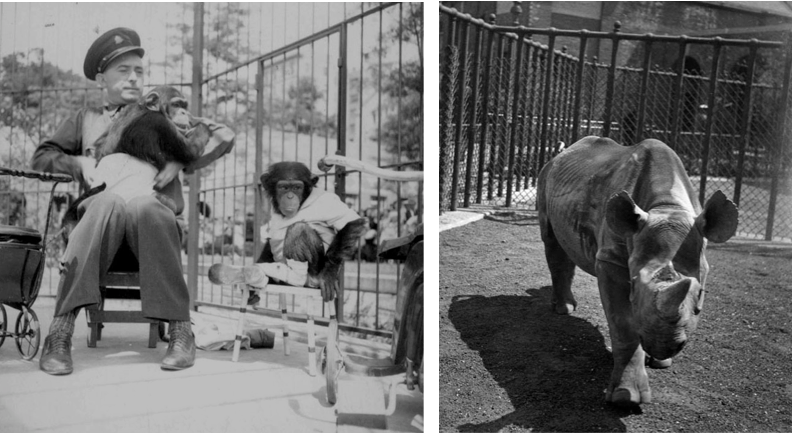

Above: The Dec. 2, 1934 opening of the reconstructed Central Park Menagerie drew such luminaries as Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, pictured at left with his family, and, at right, former New York Governor Al Smith, who was designated honorary zookeeper. Smith, who, lived across from the zoo at 820 Fifth Avenue, poses with two donkeys at the Menagerie in 1940. (New York Parks Archive)

The Central Park Zoo was not part of the original Olmstead-Vaux plan for the park, but beginning in 1859 it evolved spontaneously as a menagerie located near the Arsenal; its odd collection of animals included exotic pets donated as gifts, and other random creatures including a bear, a monkey, a peacock and some goldfish.

The menagerie accepted animals of all kinds, even sick ones, and by the 1920s the quality of the animals as well as the hodgepodge of buildings had degraded significantly (the lion house had to be guarded to prevent the animals from escaping their rotting quarters). In early 1934 Parks Commissioner Robert Moses addressed the adverse conditions in the menagerie, putting a redesign on a fast track and insisting that only healthy animals, in more humane settings, would be displayed.

Built of brick and limestone, the new zoo was designed in just sixteen days by an in-house team led by architect Aymar Embury II. Construction on the roughly six-acre zoo took just eight months, employing federally financed Works Progress Administration (WPA) labor.

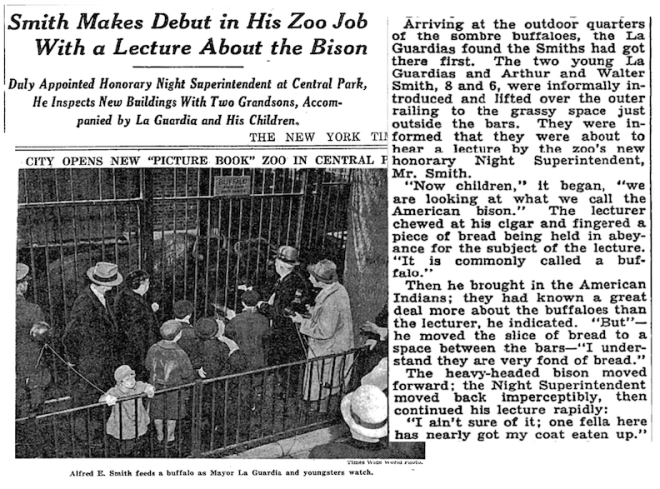

Much ado was made of Al Smith’s appointment as “Honorary Night Superintendent”—in these clips from the Dec. 3 New York Times, Smith gave a brief “lecture” about the zoo’s bison, to which he offered a slice of bread…

* * *

From Our Advertisers

R.J. Reynolds continued to roll out its list of distinguished women who preferred their Camel cigarettes: “Mrs. Allston Boyer” nee Charlotte Young was a model with the John Robert Powers agency who was married to resorts planner Allston Boyer from 1934 to 1939. Young (1914–2012) would later marry New York Times Moscow correspondent Harrison Salisbury, and the two would embark on lengthy journeys throughout Asia, including a grueling 7,000-mile journey retracing the route of The Long March that Charlotte recounted in one of her seven travel books. Whether she continued her Camel habit is unknown, but she did live 98 years…

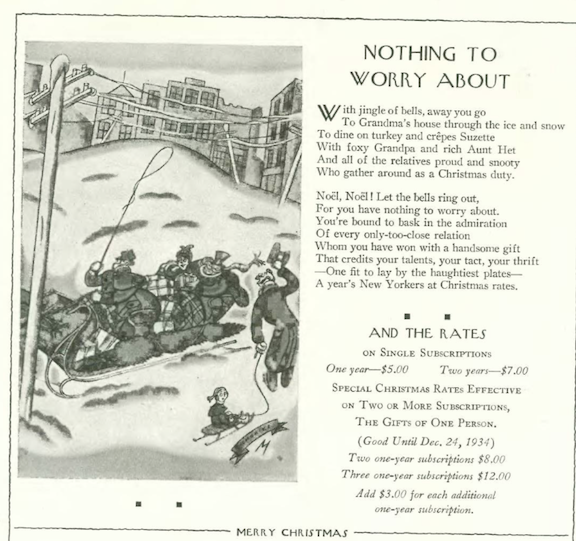

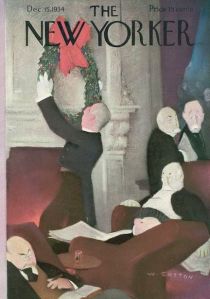

…a house ad from The New Yorker celebrated the holiday season with special Christmas rates (and Julian de Miskey embellishments)…

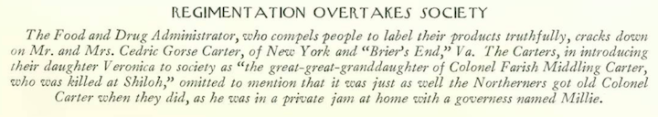

…Rea Irvin continued to have fun with the federal government’s new food and drug labeling standards…

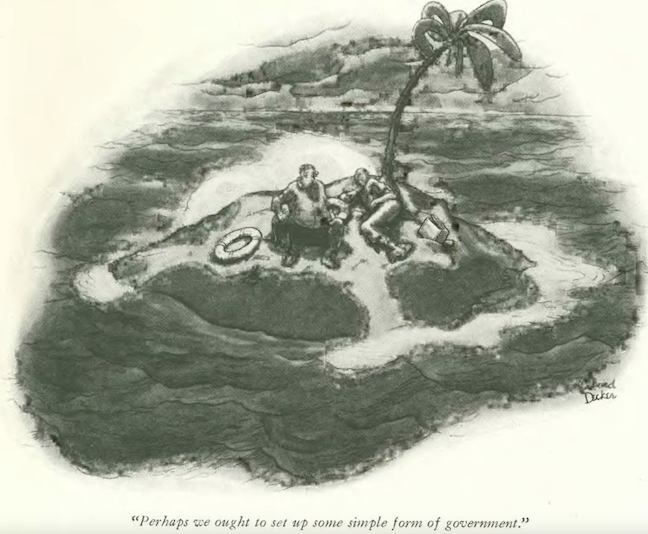

…while Richard Decker had these two castaways contemplating a simpler form of government…

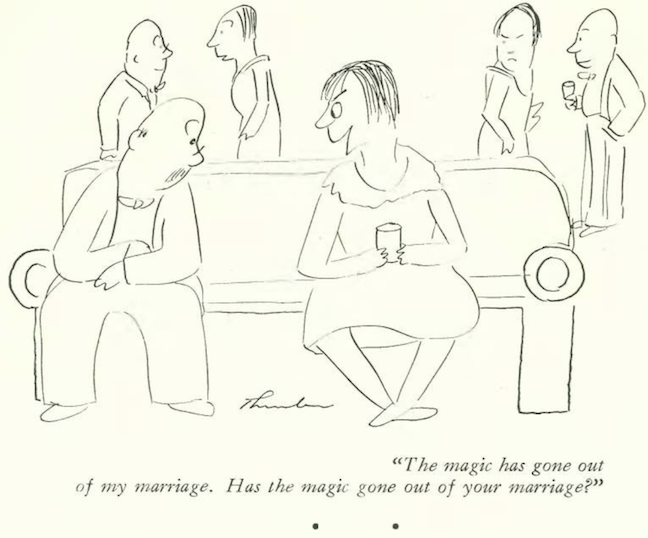

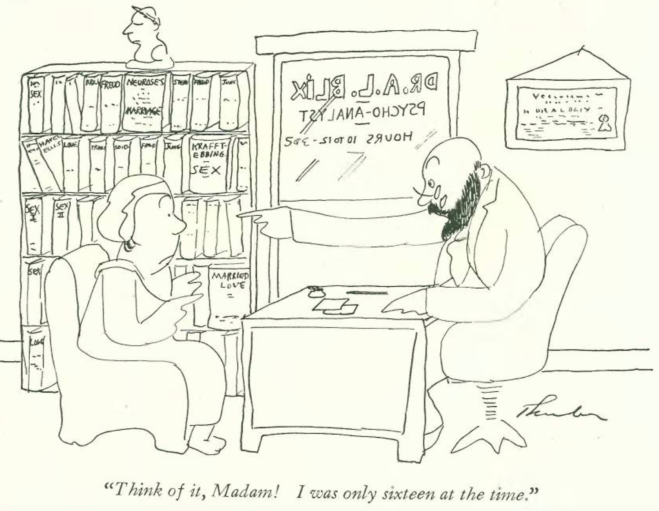

…and James Thurber continued to stir up trouble among the sexes…

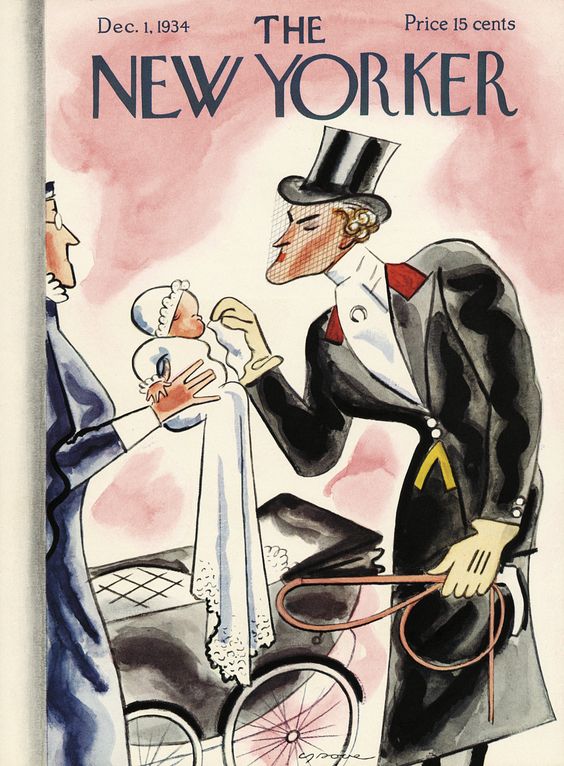

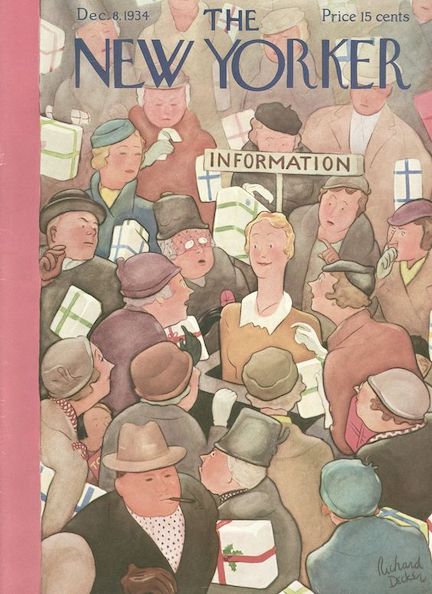

…on to Dec. 8, 1934…

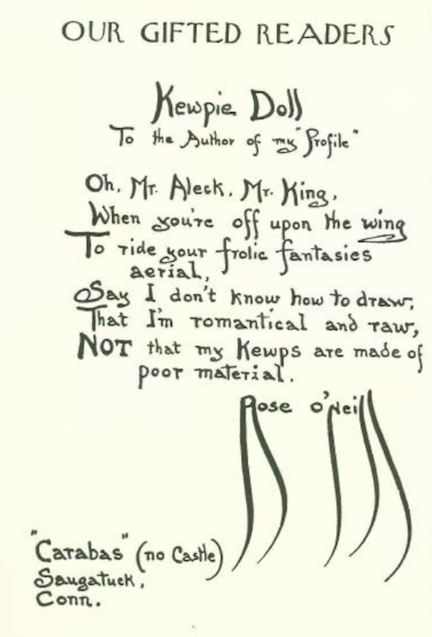

…which featured (on page 135) a handwritten letter from Kewpie Doll inventor Rose O’Neill, who commented on her recent New Yorker profile…

…here is an excerpt from the Nov. 24 profile referenced by O’Neill:

…and on to our advertisements from the Dec. 8 issue, including another Julian de Miskey-illustrated house ad…

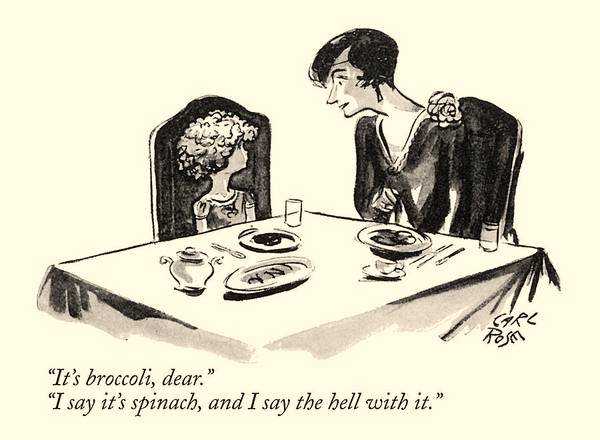

…the clever folks at Heinz enlisted the talents of Carl Rose for a play on his famous Dec. 8, 1928 New Yorker cartoon…

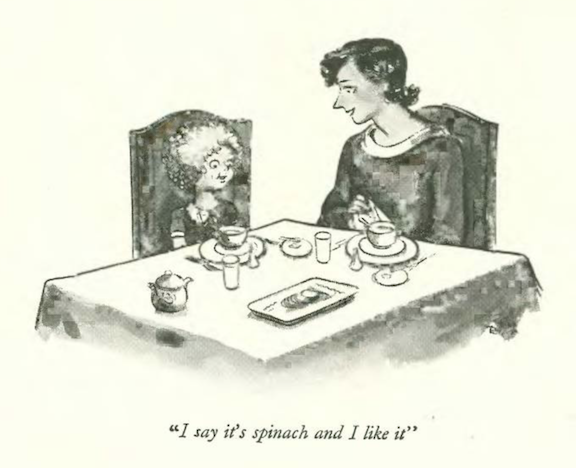

…a closer look at the illustration (note the mother’s softer, more conservative appearance, five years removed from her flapper days; the child hasn’t changed a bit, except now we can see her face)…

…and the 1928 original, with caption by E.B. White…

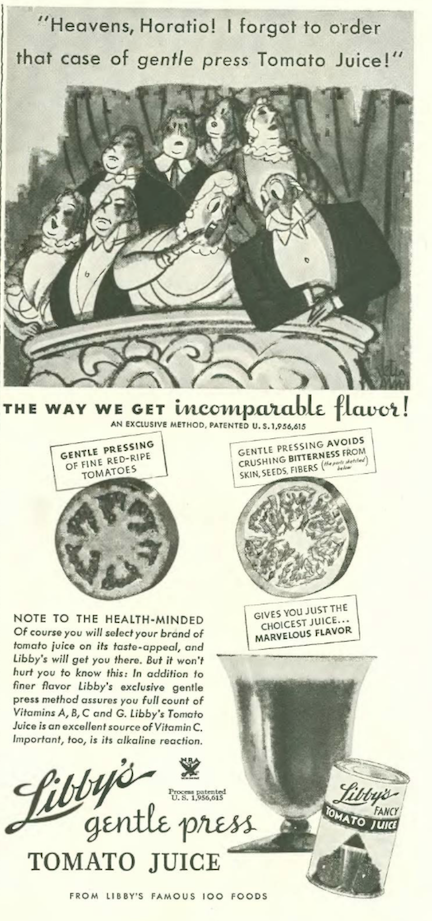

…Peter Arno also popped up in the advertising section on behalf of Libby’s…

…the magazine grew thicker with many Christmas-themed ads, including this one from Johnnie Walker…

…Marlboro continued to take out these modest, back-page ads aimed at tobacco’s growth market—women smokers…

…the makers of Spud menthol cigarettes continued their campaign to encourage chain-smoking with this rather depressing image…

…while Spud’s new competitor in menthol cigs, KOOL, kept things simple with their smoking penguin mascot and valuable coupons for keen merchandise…

…the Citizens Family Welfare Committee offered this reminder that the Depression was still very much a challenge for 20,000 New York families…

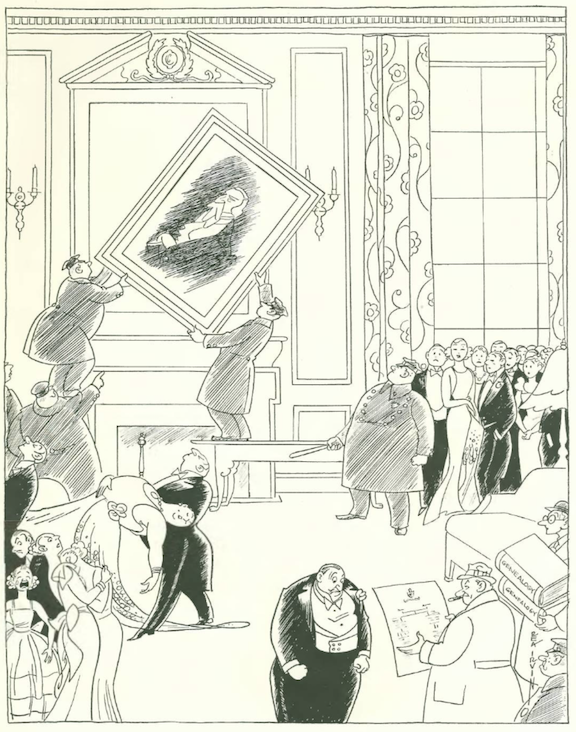

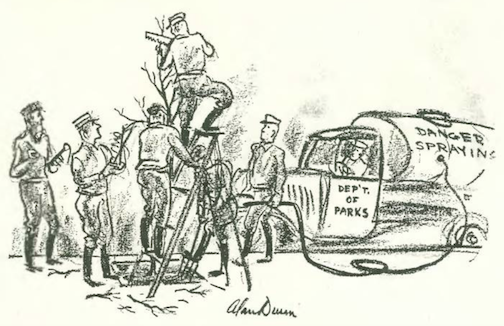

…on to our cartoonists, beginning with Alan Dunn’s rather dim view of Robert Moses’s generously funded parks department…

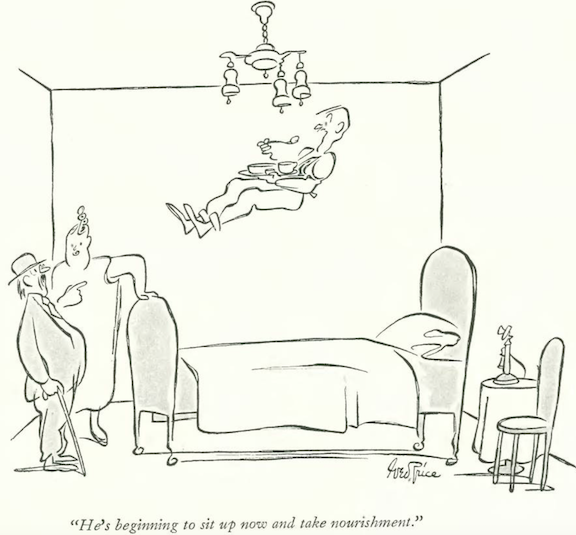

…George Price gave us the latest update on his floating man, who had been up in the air since the Sept. 22 issue…

…Daniel ‘Alain’ Brustlein marked the season with dueling Santas from Macy’s and Gimbel’s…

…and we end with James Thurber, and some reverse psychology…

Next Time: An Industrial Classicist…

“

“