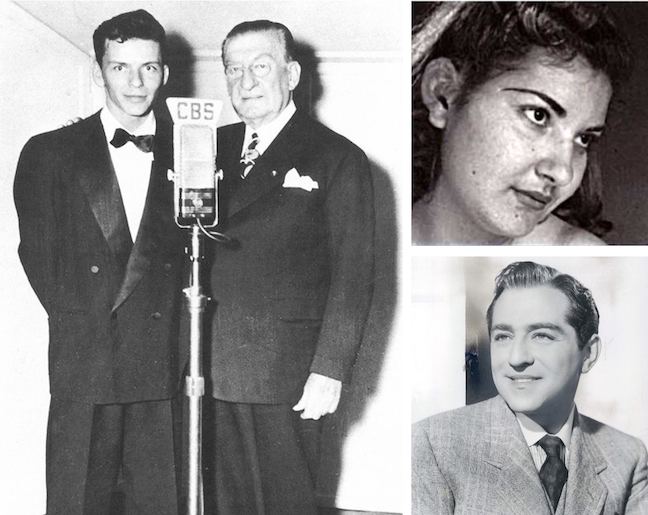

Above: Photo of the Hoboken Four as they appeared on the "Amateur Hour with Major Bowes" in 1935. At center is "Major" Edward Bowes, and at right is Frank Sinatra. The other three members of the Hoboken Four were Frank Tamburro, Patty Prince and Jimmy Petro. (knkx.org)

Nearly seventy years before American Idol appeared on our TV screens, a hugely successful and influential talent show filled the airwaves from NBC’s radio studios at Rockefeller Center.

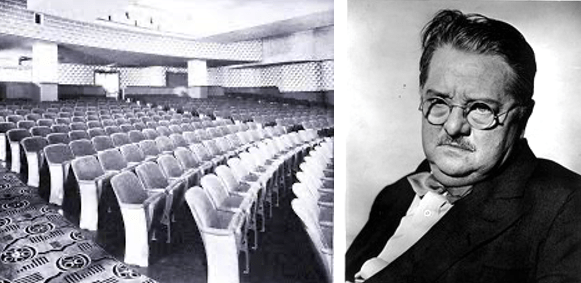

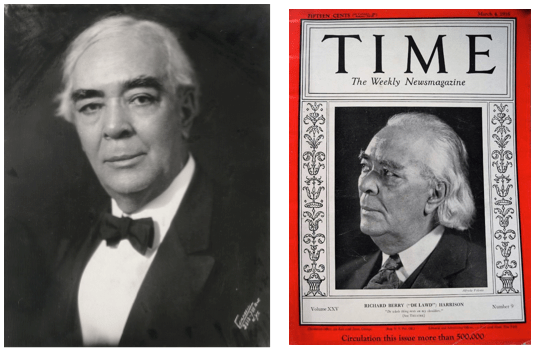

Millions tuned in each week to the Major Bowes Amateur Hour, which got its start in 1934 at radio station WHN before moving to NBC the following year. Created and hosted by “Major” Edward Bowes (1874–1946), Bowes would chat with contestants before listening to their performances, which could be cut short by the Major’s gong (see below). For his “A Reporter at Large” column, Morris Markey paid a visit to Bowes during evening auditions at the NBC studios. Excerpts:

Markey ended his piece noting the reality of the many contestants who, unlike Frank Sinatra, would not go on to successful entertainment careers.

* * *

Fleeing the Limelight

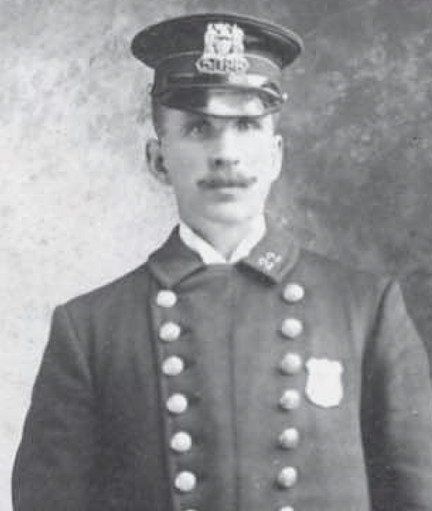

In December 1935 Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh secretly boarded a ship in New York and headed to England, seeking to escape the media frenzy that followed their son’s kidnapping and the subsequent trial. Thanks to connections through Anne’s family, they were able to move into a secluded estate in the Kent countryside. In his “Notes and Comment,” E.B. White explained:

According to White, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia cited lax police control of the media in the case of the fleeing Lindberghs. In turn, White attempted to explain the unique temperaments of Irish police officers.

A final note on the Lindberghs from Howard Brubaker, a snippet from his “Of All Things” column.

* * *

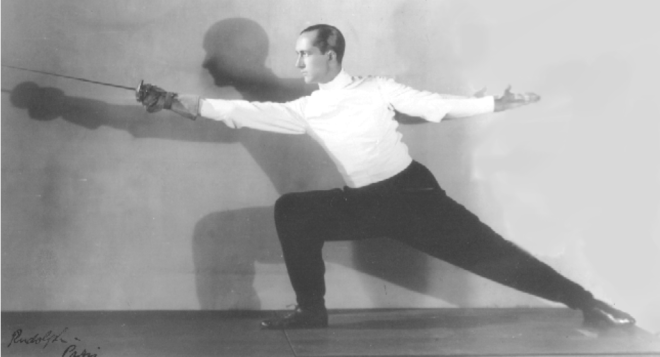

Italian Swashbuckler

The Italian fencer Aldo Naldi (1899-1965) won three gold medals and one silver at the 1920 Olympics before turning professional. According to West Coast Fencing, Aldo traveled Europe like a prizefighter, “competing in well-attended matches for cash purses…in a world of travel, glamour, drinking, womanizing, gambling and fencing, Aldo Nadi reigned supreme, going nearly eight years without a defeat.” “The Talk of the Town” was on hand for his American debut. Excerpts:

“Talk” also examined the fuss being made over the Great Chalice of Antioch, which was on display at the Brooklyn Museum. Excerpts:

* * *

Year, Schmear

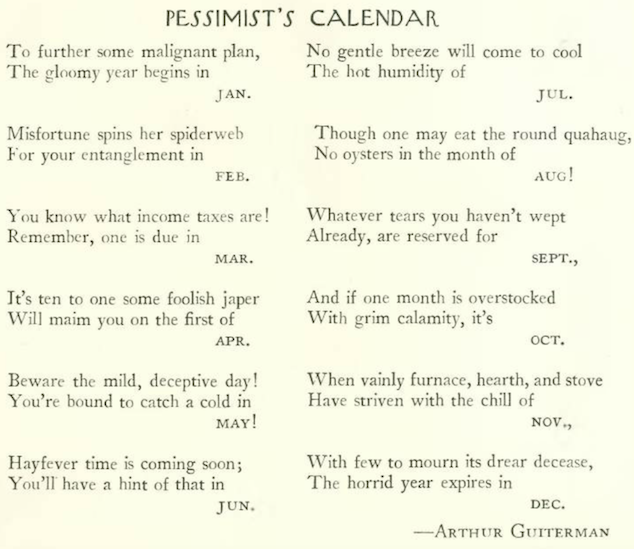

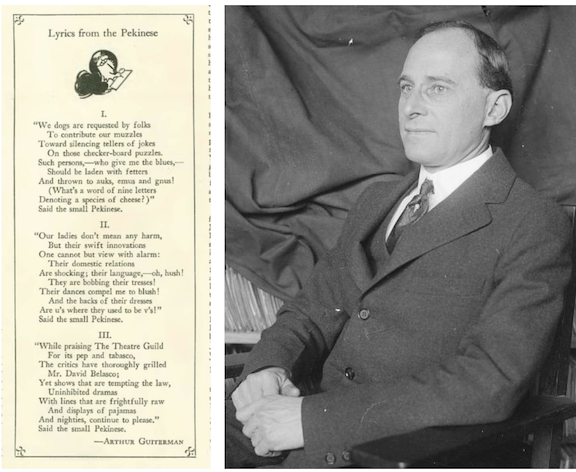

To mark the New Year, Arthur Guiterman offered up one his humorous poems…

…Guiterman (1871–1943) was an early contributor to The New Yorker—the magazine’s very first issue, Feb. 21, 1925, featured the first installment of Guiterman’s recurring “Lyrics from the Pekinese,” which ran through the first eleven issues.

* * *

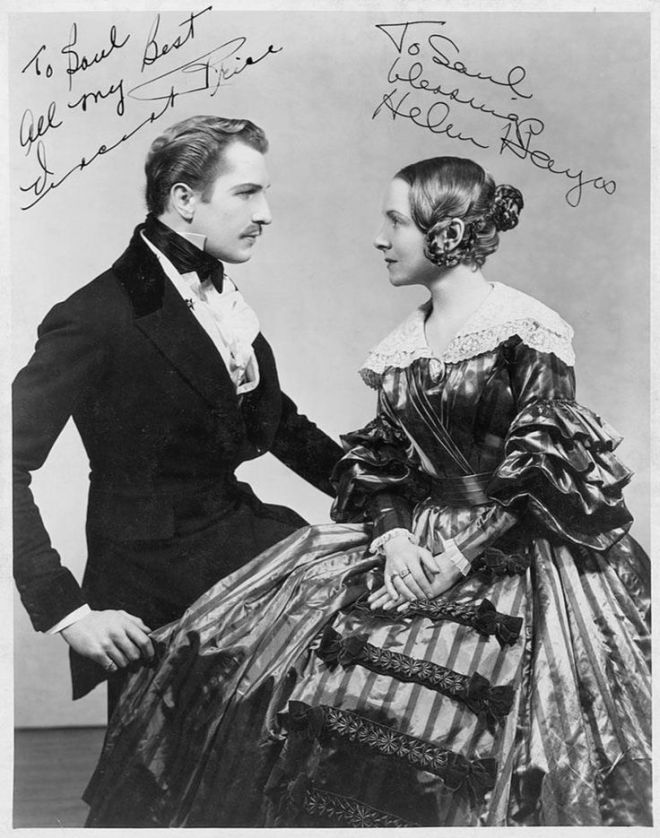

Before He Was Spooky

Robert Benchley’s review of the stage began on a bright note with Victoria Regina, which starred Vincent Price as Prince Albert and Helen Hayes as Queen Victoria. Benchley praised the realism Price and Hayes lent to the production. Excerpts:

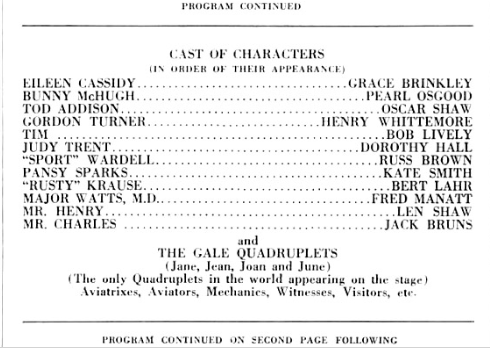

Benchley also sat through George White’s latest Scandals revue, finding it similar to White’s older shows—beautiful showgirls, various singers and dancers, and assorted comedians—with Bert Lahr shining above it all.

* * *

At the Movies

John Mosher had a busy week at the movies, finding “considerable pleasure” in the screen adaptation of Eugene O’Neill’s Ah Wilderness!…

Mosher also looked at films featuring leading actresses of the day—Barbara Stanwyck in Annie Oakley, Bette Davis in Dangerous, and Claudette Colbert in The Bride Comes Home.

* * *

Gaming the Games

In her “Paris Letter,” Janet Flanner noted the preparations for the Fourth Olympic Winter games to be held in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany.

* * *

From Our Advertisers

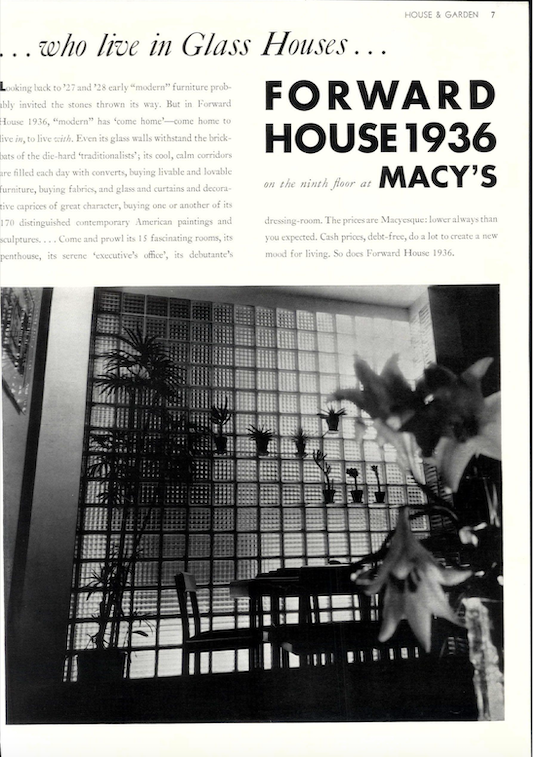

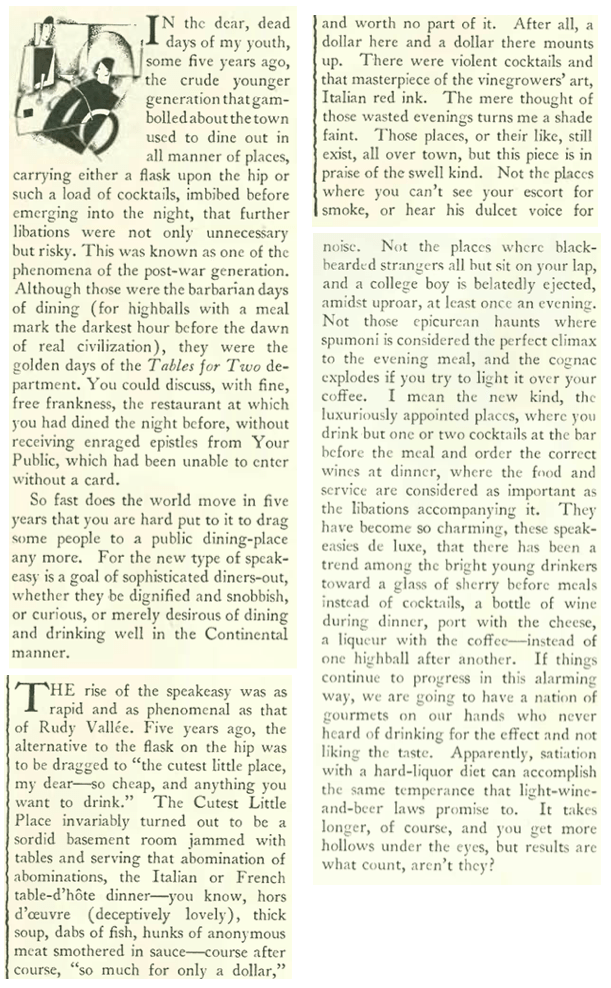

From 1933 to 1939, Macy’s hosted a series of unique design exhibitions under the title “Forward House” that showcased contemporary furniture, decor, and architectural ideas…

…for reference, here is another “Forward House” advertisement from the February 1936 House & Garden magazine…

…the folks at Robbins Island Oysters employed the legend of Giacomo Casanova to market their tasty little rocks…apparently Casanova claimed that he consumed more than fifty oysters each morning to sustain his amorous adventures…

…with the holidays over, the number of ads decreased significantly, leaving readers with a mere sixty pages—less than the half the length of the fat pre-Christmas editions…the theme in the Jan. 4 issue was travel to warmer climes, these examples culled from several back of the book pages…

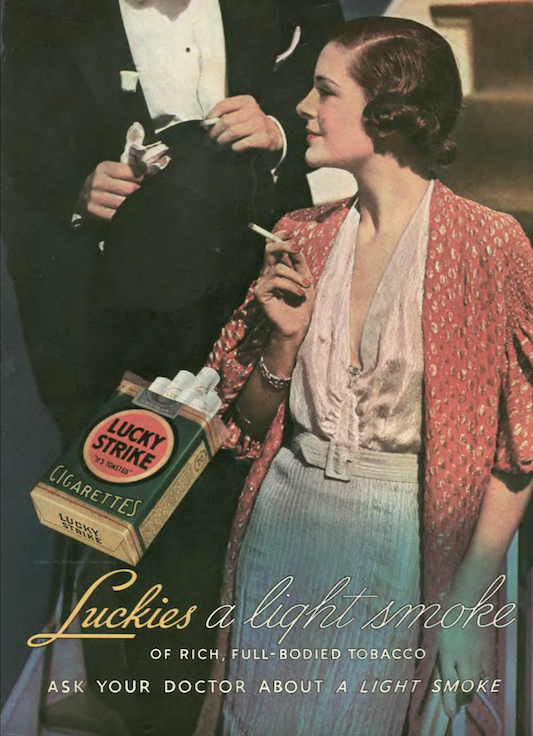

…the end of the holiday season did not stop tobacco companies from taking out lavish full-page advertisements targeting women smokers, this one gracing the back cover…note the implied medical endorsement at the bottom…

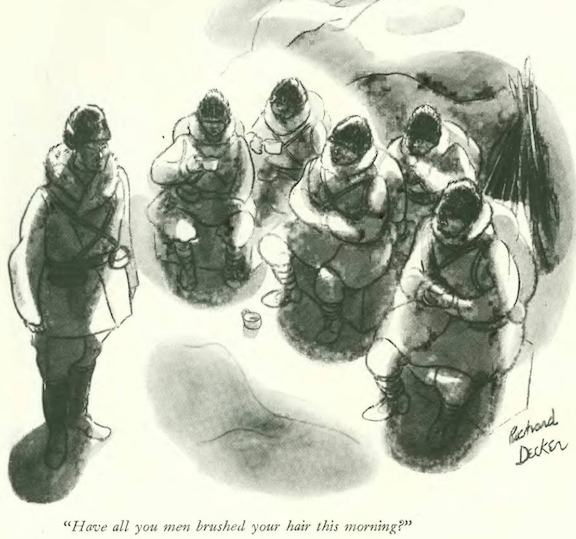

…we clear the air and move on to our cartoonists, beginning with spot drawings by D. Krán…

…and Christina Malman…

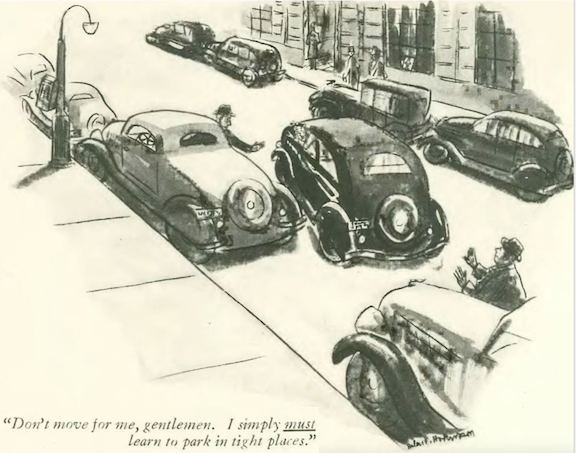

…one of Helen Hokinson’s girls sought an impromptu parking lesson…

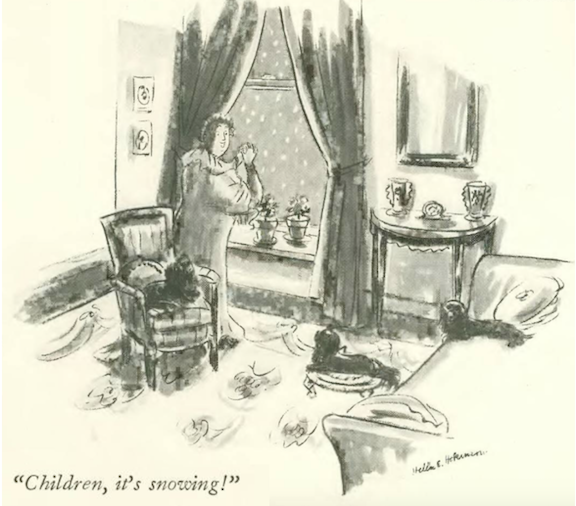

…while another welcomed winter with her furry charges…

…Whitney Darrow Jr gave us a full-service information booth…

…Mary Petty illustrated a dowager with simple tastes…

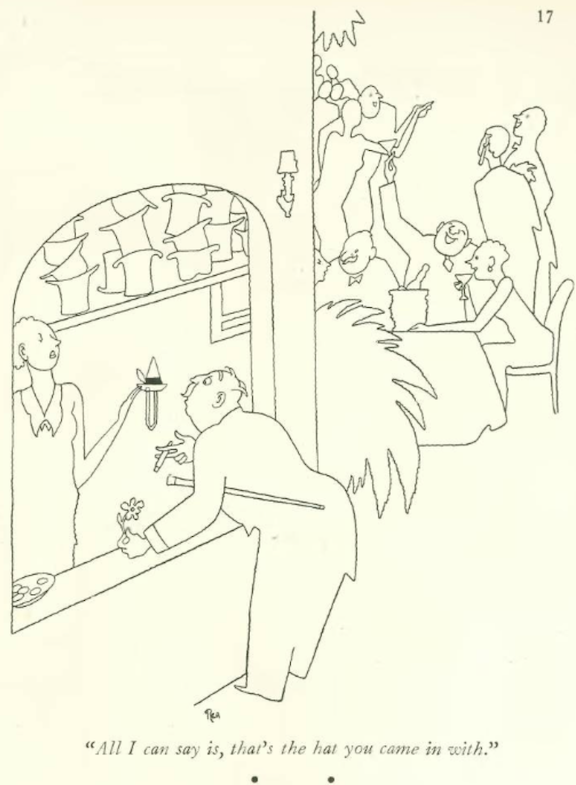

…Gardner Rea was confounded at the hat check…

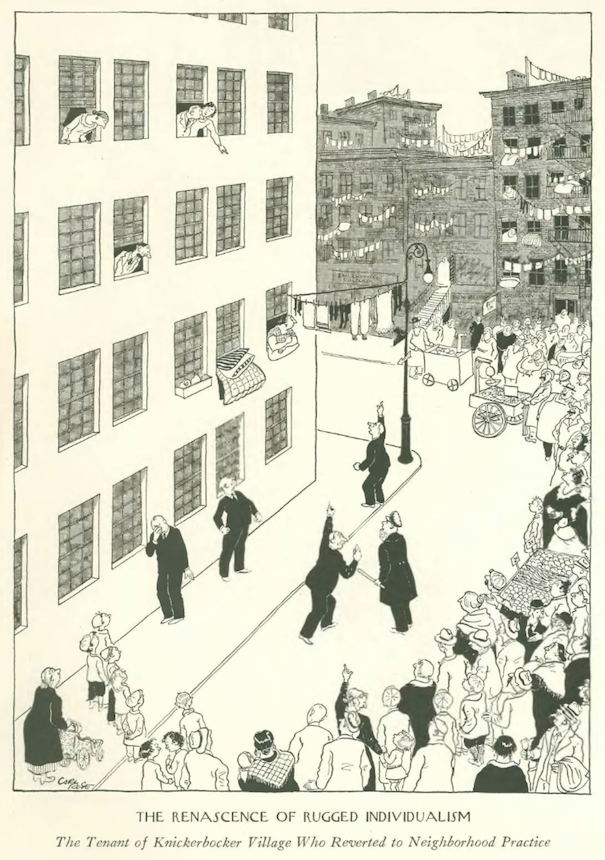

…Carl Rose offered up another example of rugged individualism…

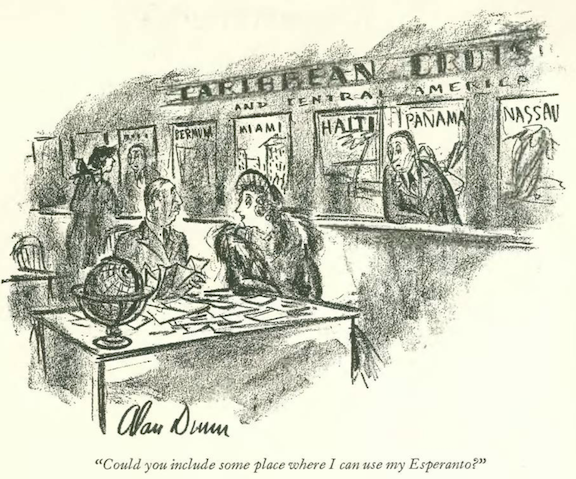

…Alan Dunn served up a unique language challenge…

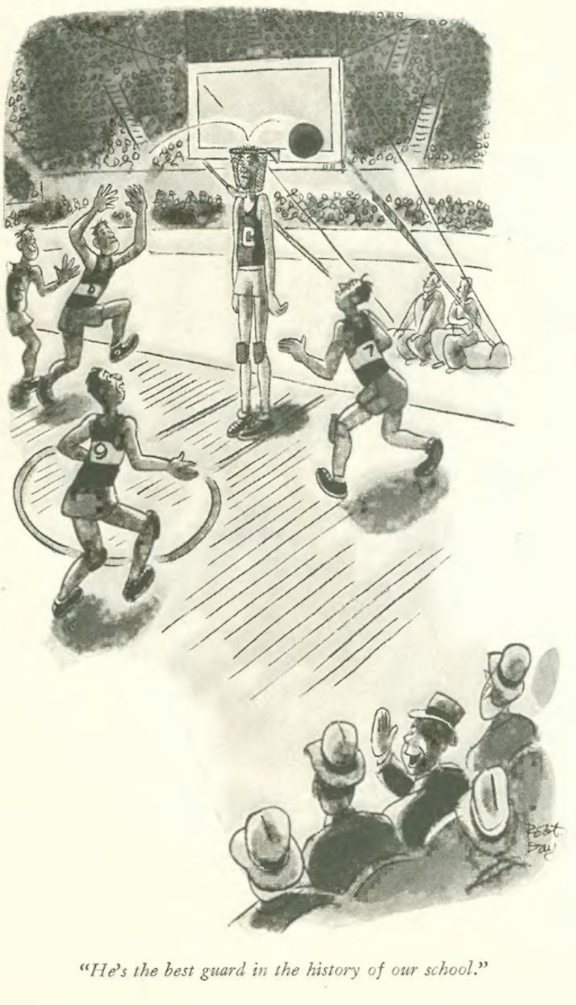

…Robert Day stood tall at a basketball game…

…William Crawford Galbraith was horsing around…

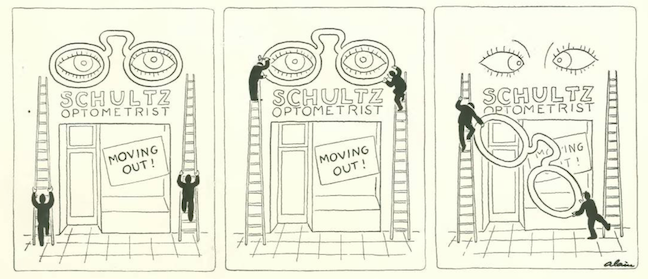

…Alain looked crosseyed at a store closing…

…and we close with Barbara Shermund, who sized up things at a hat shop…

Next Time: Magnificently Obsessed…