Heading into the dog days of summer we take a look at the last two issues of July 1935, both somewhat scant in editorial content but still offering up fascinating glimpses of Manhattan life ninety years ago.

That includes the observations of theatre critic Wolcott Gibbs and film critic John Mosher, both escaping the summer heat to take in some very different forms of entertainment.

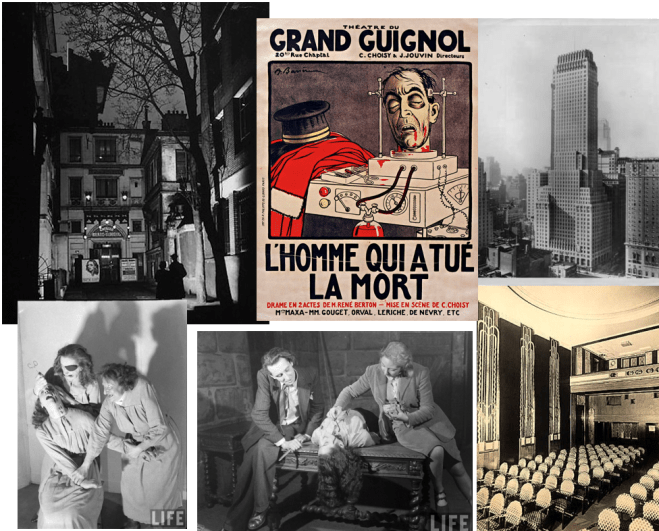

Gibbs found himself “fifty dizzy stories above Forty-second Street” in the Chanin Building’s auditorium, where he experienced New York’s take on Le Théâtre du Grand-Guignol. Founded in Paris by Oscar Méténier in 1897, Grand Guignol featured realistic shows that enacted, in gory detail, the horrific existence of the disadvantaged and working classes. It seems audiences were drawn to the shows more out of prurient interest (or sadistic pleasure) than for any desire to help the underclasses.

* * *

Popeye to the Rescue

With the Hays Code in effect you wouldn’t see anything like the Grand-Guignol on the silver screen. Indeed, with the exception of a Popeye cartoon, critic John Mosher found little to get excited about at the movies. He did, however, enjoy the air conditioning that offered a break from the hot city streets.

* * *

From Our Advertisers

Just a few ads from this issue, first, a jolly appeal from one of the magazine’s newer advertisers, the makers of the French apertif Dubonnet…

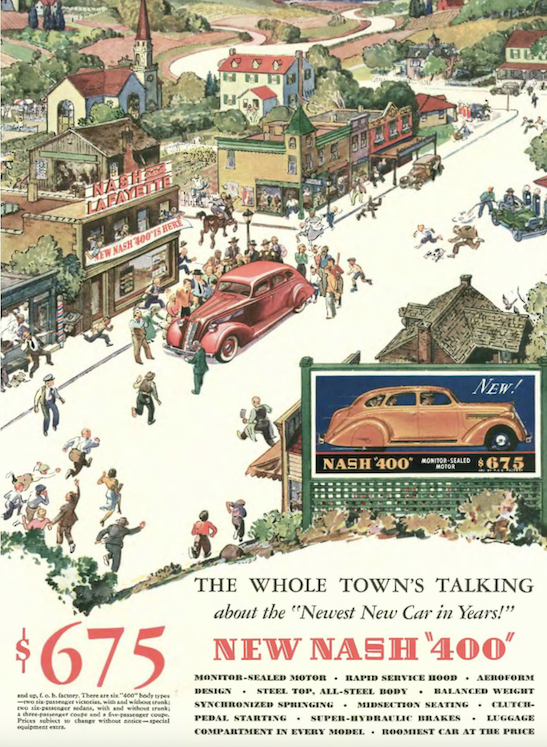

…by contrast, this quaint slice of Americana from Nash…

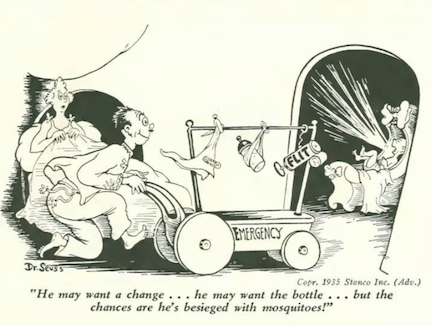

…and a shot of pesticide from Dr. Seuss…

…our cartoonists include Constantin Alajalov, contributing this bit of spot art to the opening pages…

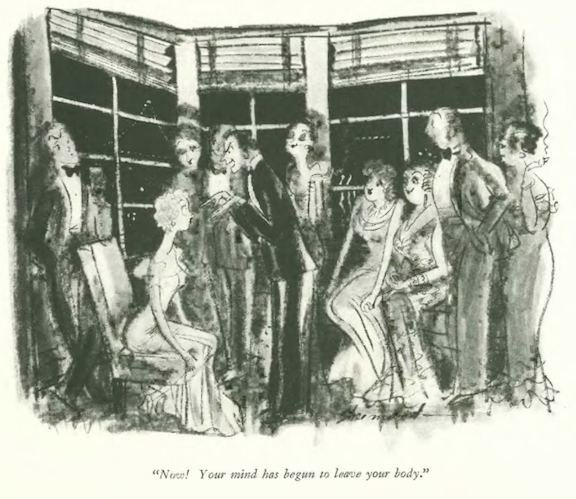

…Barbara Shermund explored the world of hypnotic suggestion…

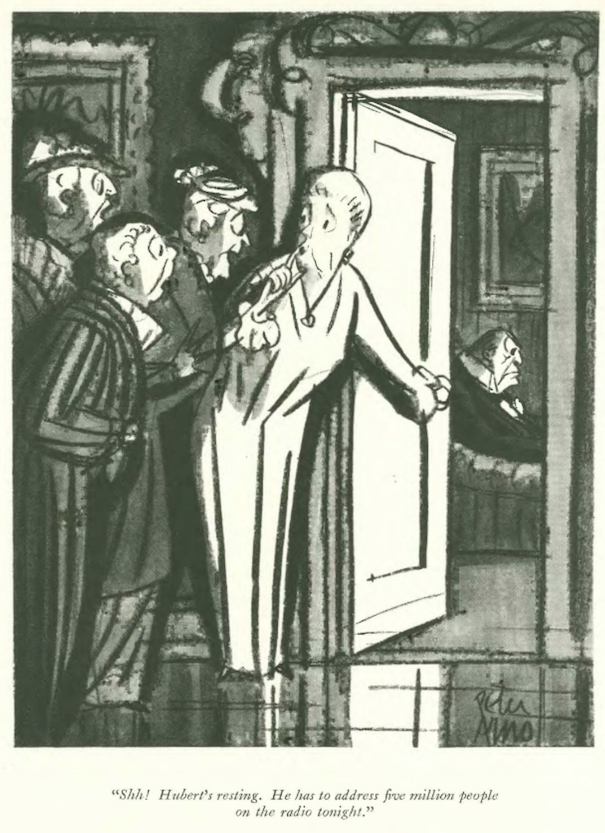

…Peter Arno prepared to address the nation…

…William Steig checked the weather forecast…

…Helen Hokinson’s girls questioned the burden of a lei…

…Carl Rose found himself on opposite sides of the page in this unusual layout…

…Richard Decker joined the crowd in a lighthouse rendering…

…Ned Hilton reminds us that it was unusual for women to wear trousers ninety years ago…

…Mary Petty examined the complications of marital discord…

…and Charles Addams shone a blue light on a YMCA lecture…

…on to July 27, 1935, with a terrific summertime cover by William Steig…

E.B. White (in “Notes and Comment”) was ahead of his time in suggesting that the city needed to build “bicycle paths paralleling motor highways” and invest in more pedestrian pathways.

* * *

Breaking News

“The Talk of the Town” checked in on the New York Times’ “electric bulletin,” commonly known as “The Zipper.” Excerpt:

* * *

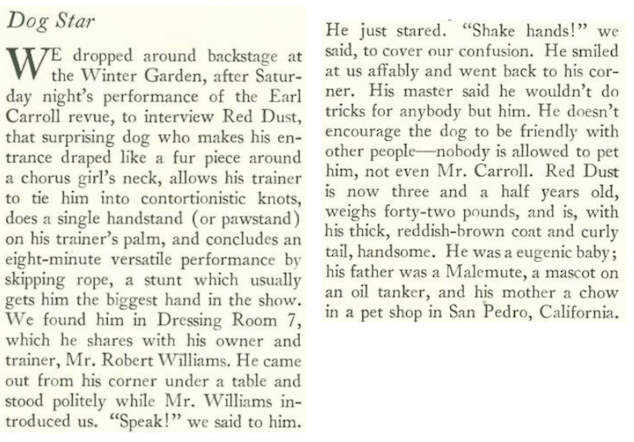

Dog Knots

“Talk” also took a look backstage at the Winter Garden, where burlesque performers shared the stage with a contortionist dog called “Red Dust.” Excerpt:

* * *

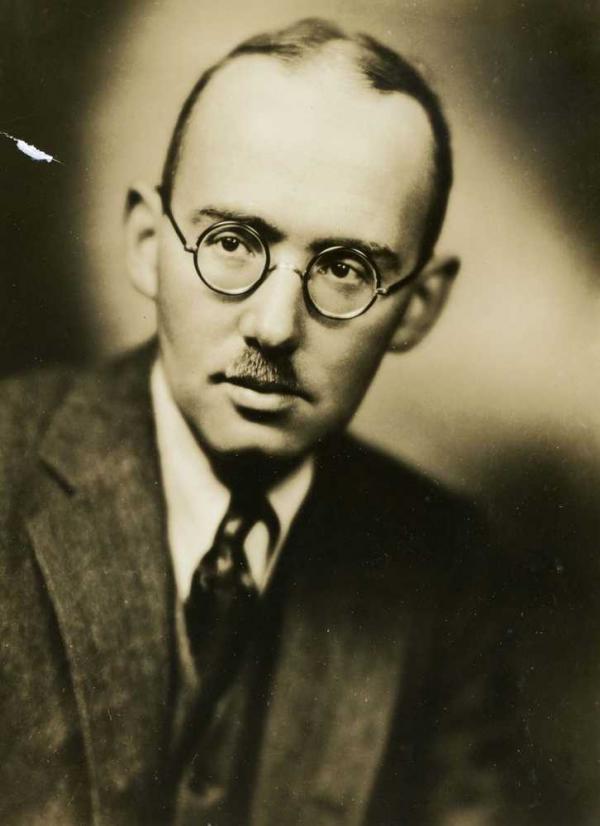

Suddenly Famous

Charles Butterworth (1896-1946) earned a law degree from Notre Dame before becoming a newspaper reporter. But his life would take on a new twist in 1926 when he delivered his comical “Rotary Club Talk” at J.P. McEvoy’s Americana revue in 1926. Hollywood would come calling in the 1930s, and his doleful-looking, deadpan characters would become familiar to movie audiences through a string of films in the thirties and forties. Alva Johnston profiled Butterworth in the July 27 issue. Here are brief excerpts:

* * *

Noisy Neighborhood

The “Vienna Letter” (written by “F.S.”–possibly Frank Sullivan) noted the rumblings of fascism in a grand old European city known for its many cultural delights as well as its many factions that included Nazis, Socialists and Communists (and no doubt a few Royalists). An excerpt:

* * *

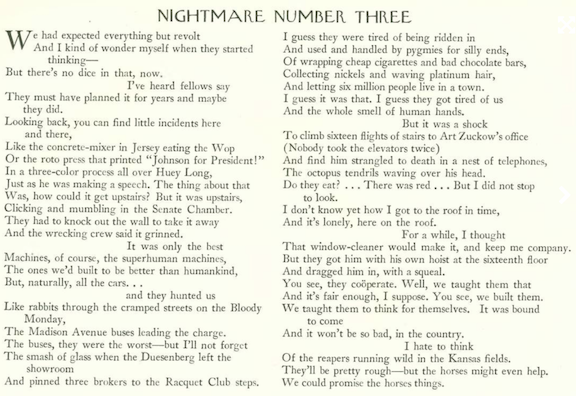

Ex Machina

The Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and author Stephen Vincent Benét (1898-1943) penned this poem for The New Yorker that is somewhat appropriate to our own age and our fears of the rise of A.I. In “Nightmare Number Three,” Benét described a dystopian world where machines have revolted against humans.

* * *

From Our Advertisers

We begin with more extraordinary claims from R.J. Reynolds, who convinced a lot of folks that drawing smoke into your lungs actually improved your athletic stamina…

…the makers of Lucky Strike, on the other hand, stuck with images of nature and romance to suggest the joys of inhaling tar and nicotine…

…General Tire took a cue from Goodyear, suggesting that an investment in their “Blowout-Proof Tires” was an investment in the very lives of a person’s loved ones (even though they apparently drove to the beach without seatbelts or even a windshield)…

…another colorful advertisement from the makers of White Rock, who wisely tied their product to ardent spirits as liquor consumption continued to rebound from Prohibition…

…I toss this in for the lovely rendering on behalf of Saks…it looks like the work of illustrator Carl “Eric” Erickson, but he had many imitators…

…we do, however, know the identity of this artist, and his drawings on behalf of the pesticide Flit, which apparently in those days of innocence was thought appropriate for use around infants…

…great spot drawing in the opening pages…I should know the signature but it escapes me at the moment…

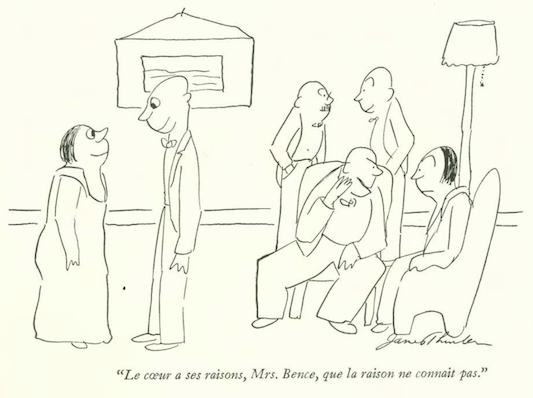

…James Thurber quoted Blaise Pascal for this tender moment ( “The heart has its reasons, of which reason knows nothing”)…

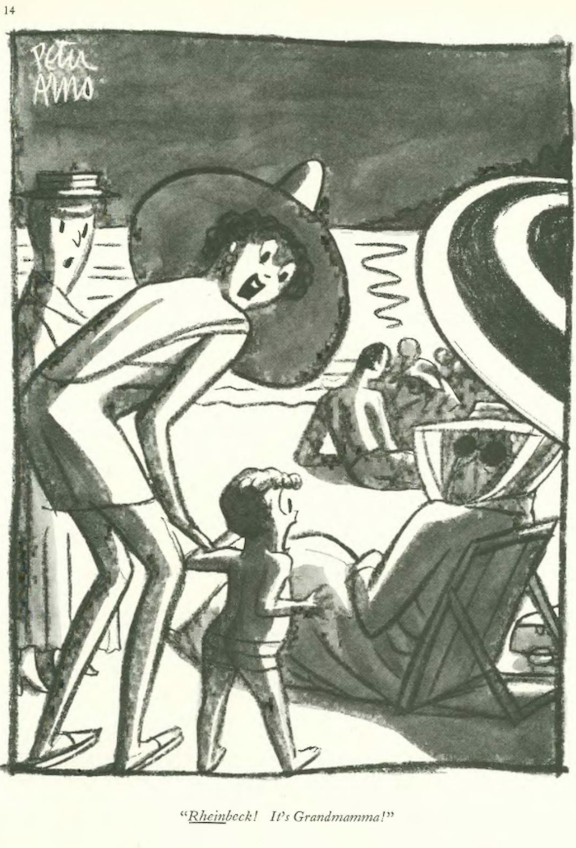

…Peter Arno illustrated the horrors of finding one’s grandmother out of context…

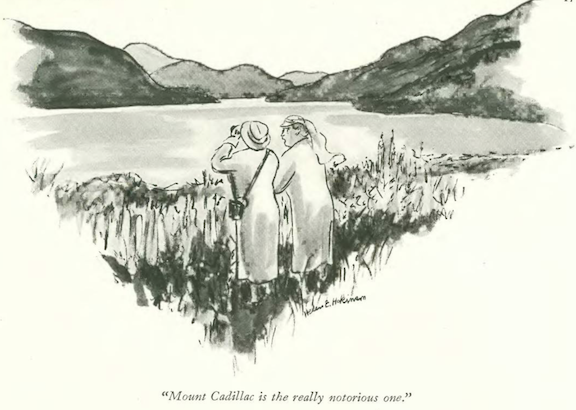

…Helen Hokinson’s girls employed a malaprop to besmirch the good name of an innocent mountain…

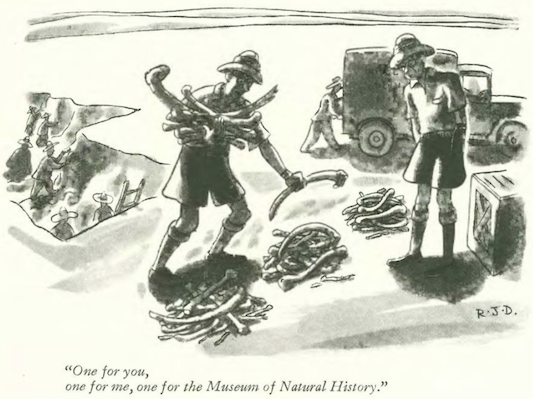

…Richard Decker discovered the missing link(s) with two archeologists…

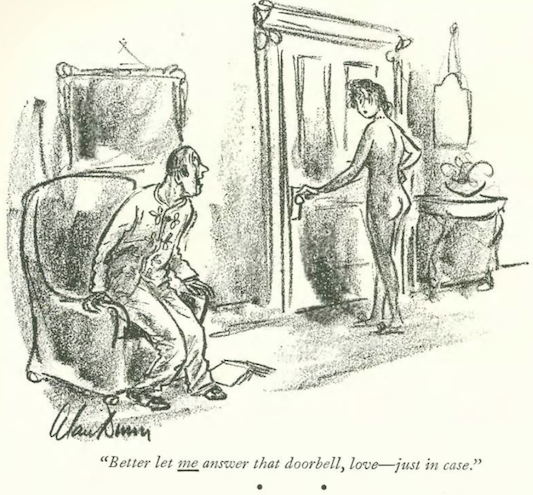

…Alan Dunn narrowly averted a surprise greeting…

…George Price added a new twist to a billiards match…

…Price again, at the corner newstand…

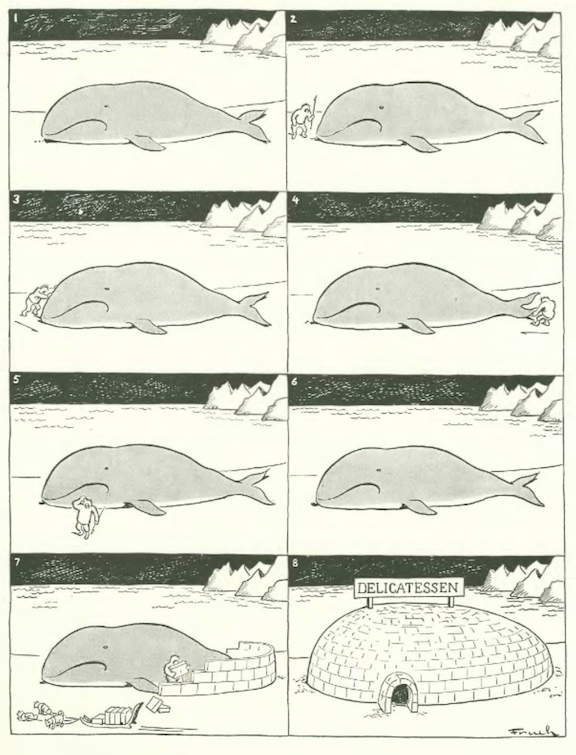

…Al Frueh bit off more than he could chew…

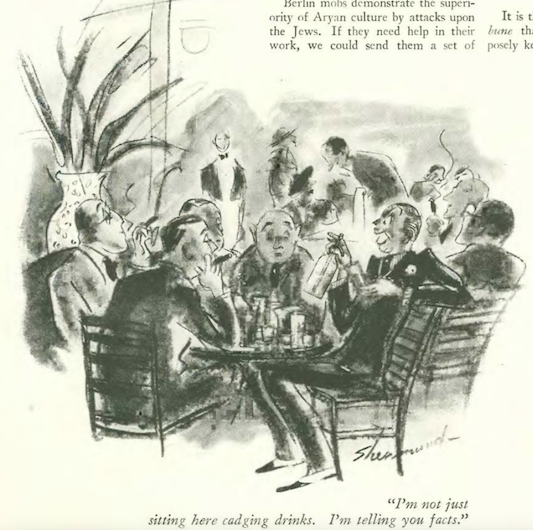

…and we close with Barbara Shermund, and a prattling mooch…

Next Time: La Marseillaise…