-

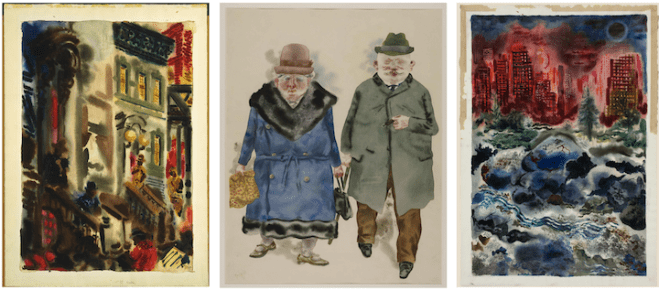

Above: Landscape in Bayside, 1935, by George Grosz (Phillips Collection)

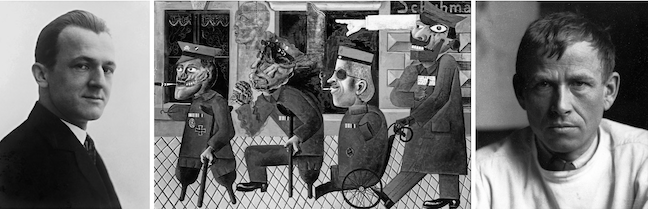

Knowing that the Nazis would not look kindly on his art, George Grosz took a job teaching drawing in New York in 1932, and by 1933 he had become a permanent resident of the city.

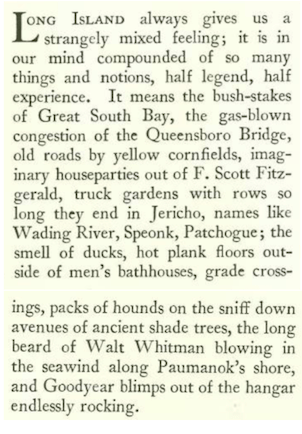

Grosz (1893–1959) was overwhelmed by the size and pace of his adopted city, and for the most part he left behind his bitter caricatures and paintings of Berlin’s Weimar years and turned to other subjects, including landscapes and New York’s urban life. Critic Lewis Mumford took in a show of Grosz’s new water colors at An American Place, a small gallery run by photographer and art dealer Alfred Stieglitz.

-

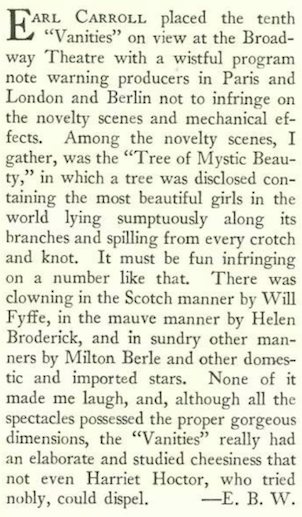

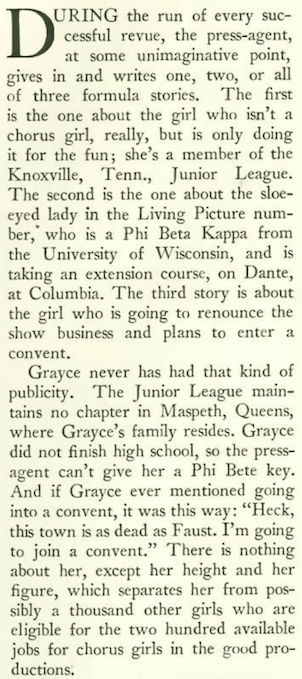

* * *Not the Bee’s KneesFor all the progressive thinking that was on display in the early New Yorker, we also reminded that it was also a creature of its time in 1935. Here are excerpts from a lengthy “Talk of the Town” entry that described the sad winnowing process of Broadway revue producer Earl Carroll…

* * *

Too Little For Too Much

Film critic John Mosher gave Alfred Hitchcock’s 1934 version of The Man Who Knew Too Much just five lines in his review. He described it as “one of those preposterous adventure stories which Englishmen are always writing…” The film, however, was an international success, and it would define the rest of Hitchcock’s career as a director of thrillers with a unique sense of humor.

* * *

Dizzy Nor Dazzled

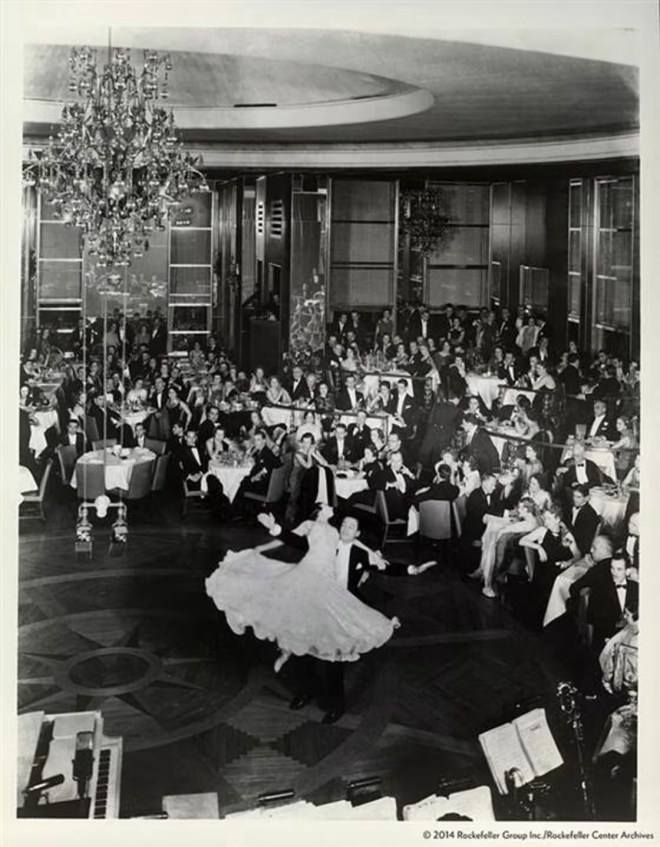

In 1935 Lois Long had been divorced from cartoonist Peter Arno for about four years, and she was the mother of six-year-old daughter from that marriage. That didn’t keep her from sampling the city’s night life, but the days of speakeasies and drinking sessions that lasted into the wee hours were over for the 34-year-old Long. For her “Tables for Two” column she took the elevator up to the 65th floor of 30 Rockefeller Plaza to take in the entertainment at the Rainbow Room…as well as the pedestrian crowd…

…her speakeasy days were over, but it appears Long still enjoyed a bit of indulgence…here is how she concluded her column:

* * *

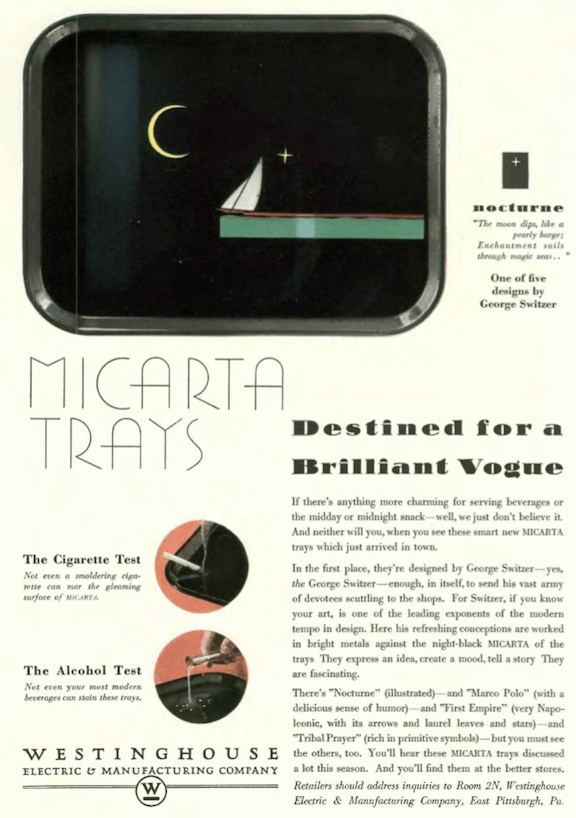

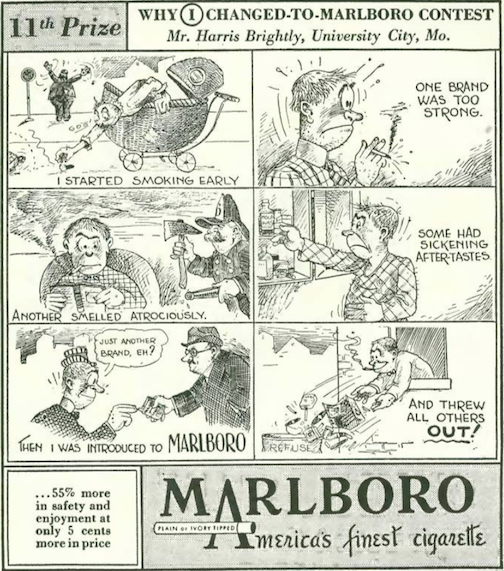

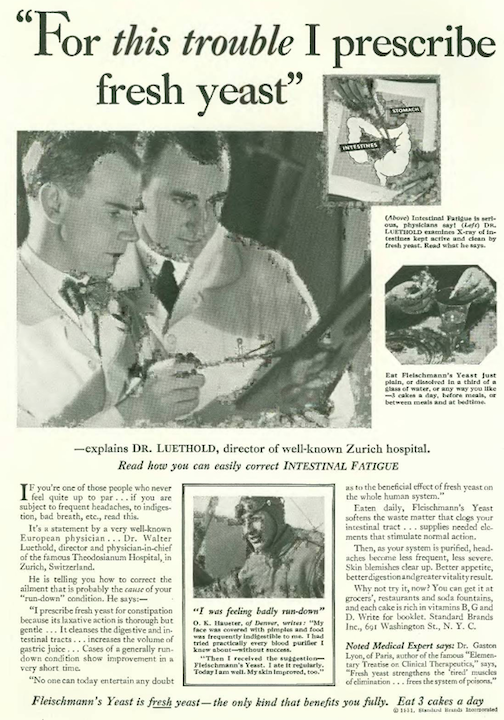

From Our Advertisers

Step into a crowded mid-century elevator and you were bound to catch a whiff of the menthol-tinged scent of Aqua Velva, not objectionable if properly applied…

…speaking of menthol, the makers of Spud cigarettes were now competing with upstart menthol cigarette makers including Kool…this ad has all kinds of problems, including the suggestion that the occasional Spud not only inspires one’s nuptials, but also ensures marital bliss, as well as a lifetime of chain-smoking…

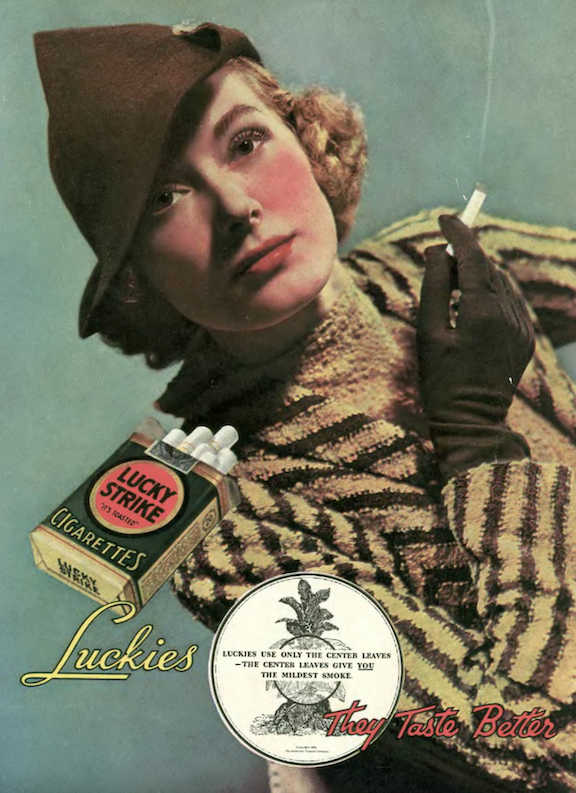

…Luckies, on the other hand, continued to appeal to the modern woman, and what impressionable young woman wouldn’t be inclined to pick up the habit to complete her ensemble?…

…the makers of College Inn tomato juice gave their raving Duchess the week off, but we get another old sourpuss in the form of a “Dowager” who demands that her servant remove a glass of what very well could have been tomato juice…enter the old bat’s niece, Dorothea, who suggests that the cook, Clementina, serve some Libby’s pineapple juice instead, probably spiked with vodka given the Dowager’s sudden change of demeanor…

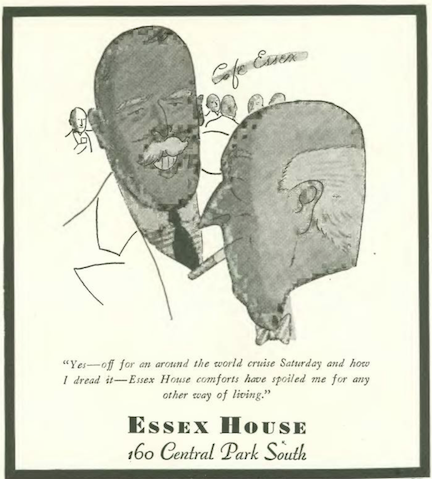

…Essex House continued their class-ridden ad campaign, this time with some stuff-shirt dreading his world cruise

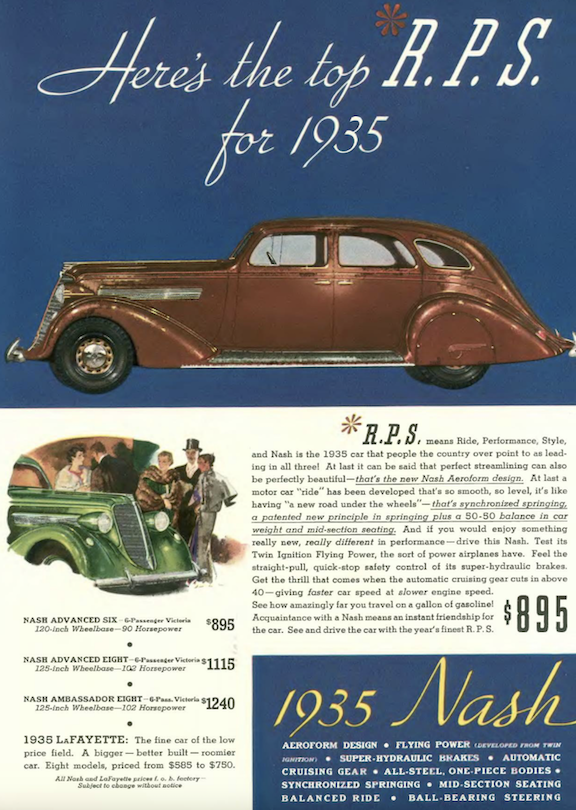

…carmakers continued to emphasize economy and price to move their latest models, including the 1935 Nash with “Aeroform Design”…

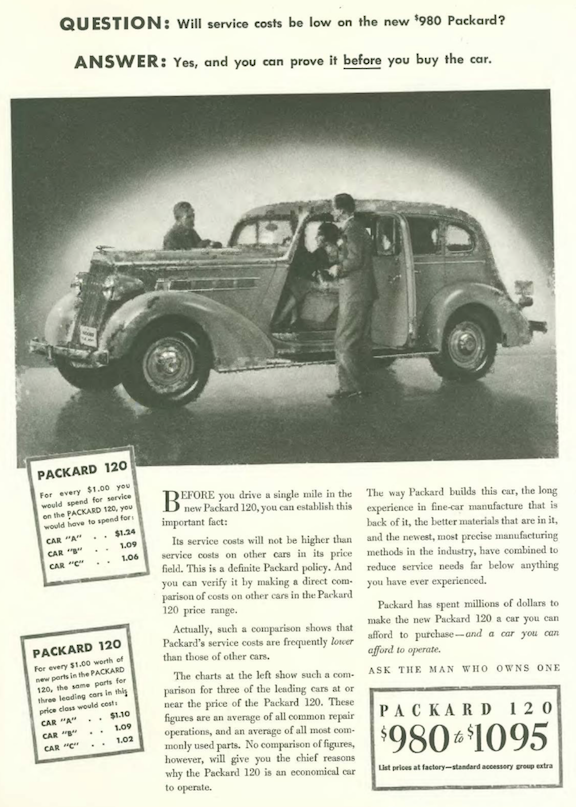

…last week I noted that Packard was doubling down on promoting the elite status of its premium automobile; however, the carmaker did introduce a “120” that cost a fraction of its luxury models and helped the company’s bottom line…

…Packard’s competition was Lincoln and Cadillac, among other luxury brands, but Pierce Arrow represented the pinnacle of luxury and craftsmanship, the American equivalent of Rolls Royce…unlike the other luxury brands, Pierce Arrow did not offer a lower-priced car, and the company folded it 1938…

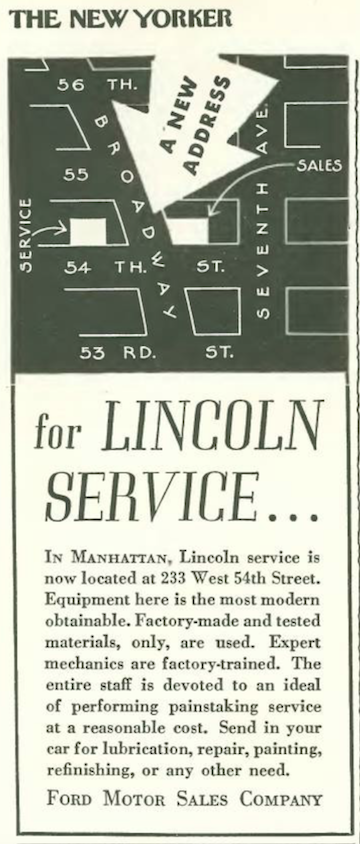

…speaking of luxury cars, if you owned a Lincoln, this little ad tucked into the top corner of page 55 showed you were to go to get a tune-up…

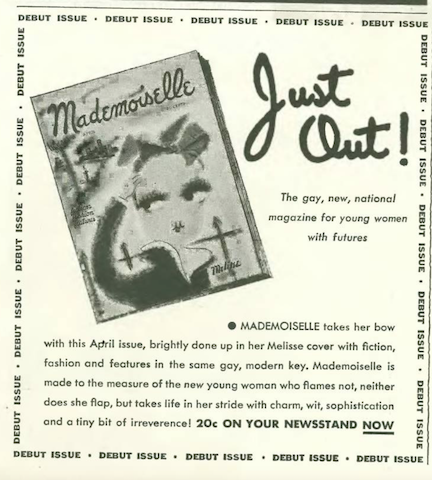

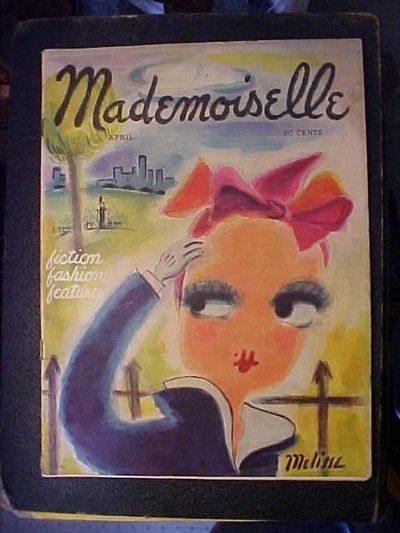

…the publishers at Street & Smith announced the launch of a new fashion magazine, Mademoiselle, a seemingly daring move in Depression America…the cover featured an illustration by Melisse (aka Mildred Oppenheim Melisse)…the magazine was later acquired by Condé Nast, and folded in November 2001…

…Otto Soglow was on his way to becoming a wealthy man thanks to his “Little King” cartoon…William Randolph Hearst lured Soglow and the cartoon away from The New Yorker in 1934, so the only way the wee potentate could appear in the magazine was in an ad, like this one for Bloomingdale’s…

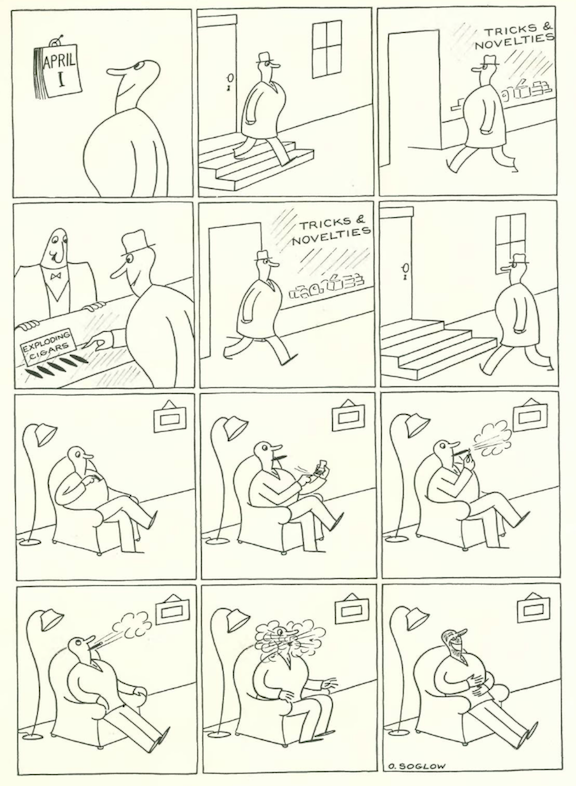

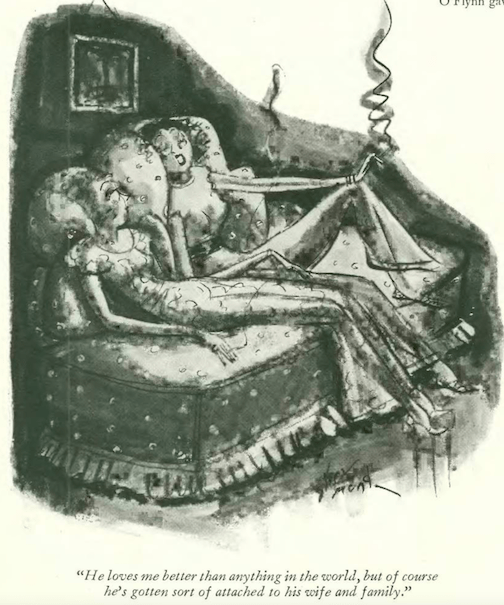

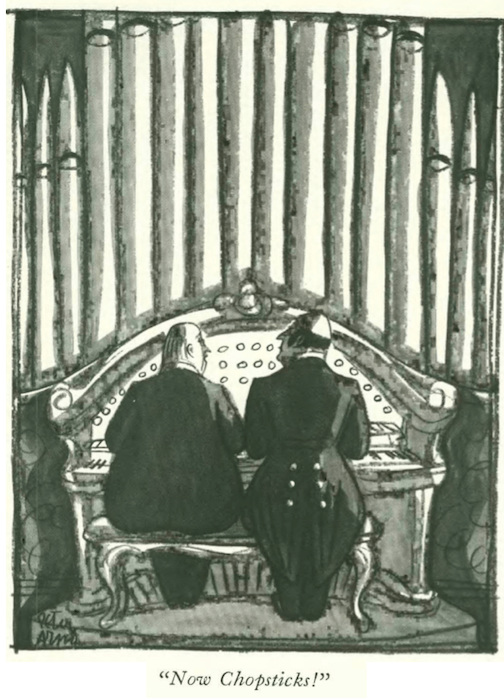

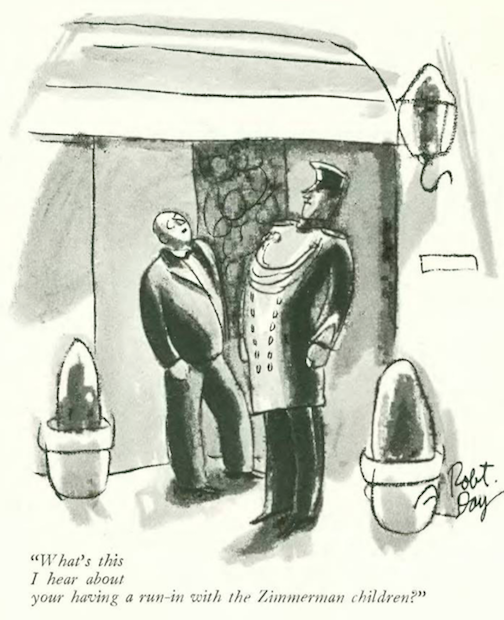

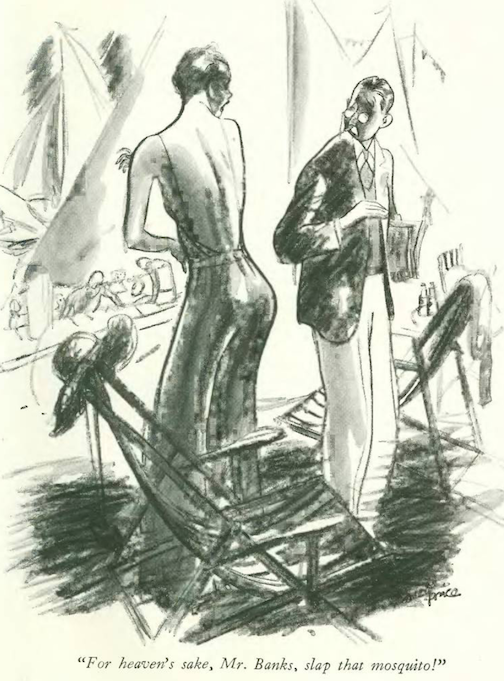

…Soglow continued to contribute to The New Yorker, and we kick off our cartoons with an April Fool’s joke…

…for the second week in a row Maurice Freed supplied the opening spot art for “Goings On About Town”…

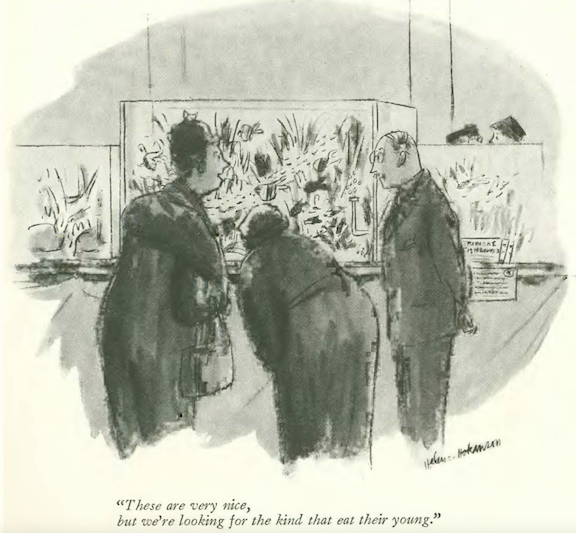

…Helen Hokinson was on the hunt for some predatory fish…

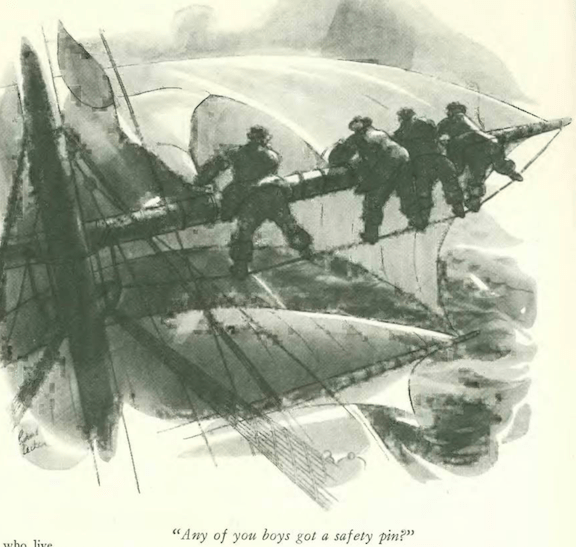

…James Thurber looked in on the nudist fad that emerged in the 1930s…

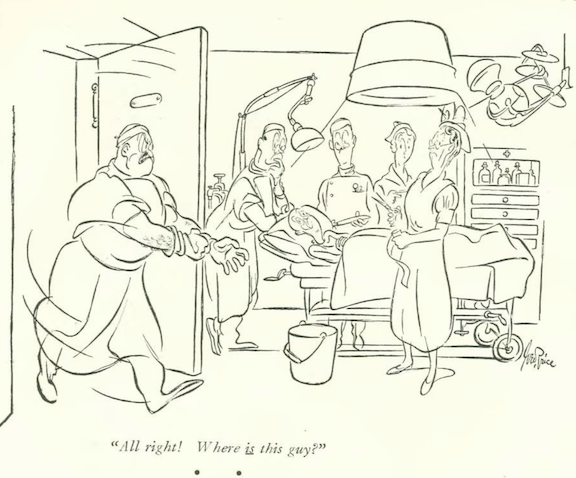

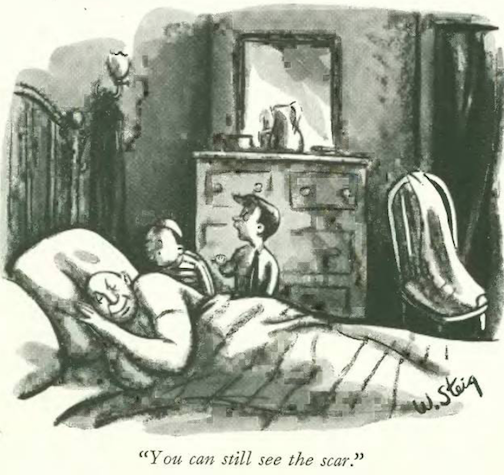

…and we close with George Price, an some alarming bedside manners…

Next Time: Keep Calm and Carry On…