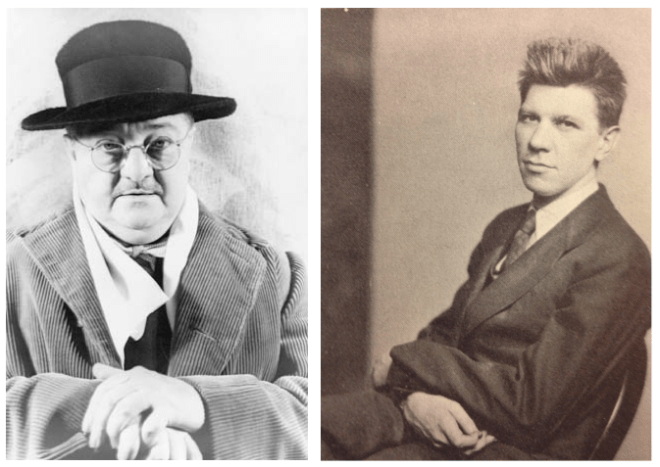

The evolution of filmmaking in the 1920s included the development of “docudramas.” Nanook of the North (1922), which captured the struggles of an Inuit hunter and his family, was received with great acclaim. A few years later Grass (1925), directed by Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack, followed a tribe in Iran as they guided herds to greener pastures. So when Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness opened at the Rivoli, The New Yorker was there (May 7, 1927) to share in the adventure.

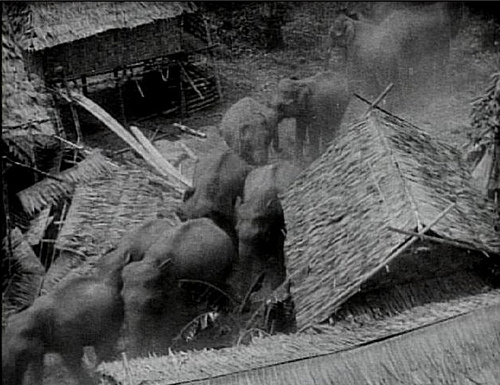

Chang, also directed by Cooper and Schoedsack, told the story of a poor farmer and his family (native, nonprofessional actors) in Issan—now northeastern Thailand—and their constant struggle for survival in the jungle. Cooper and Schoedsack attempted to depict real life but often re-staged events. The danger, however, was real to all involved, as was the slaughter of animals in the film.

According to Ray Young, writing for Viennale, the website for the Vienna International Film Festival (which is screening a retrospective of Chang this fall) Cooper and Schoedsack “open with scenes of domestic bliss and, offsetting title card warnings of the dangers of the jungle, a bucolic Eden ripe for development. But the tone soon shifts as tigers and leopards attack, and the picture evolves into a succession of episodes concerning their survival.”

The perils in Chang often feel rigged, notes Young, “most conspicuously in places where animals appear to have been killed simply for the benefit of the camera. By most accounts, Schoedsack did most of the filming while Cooper covered him with a rifle.”

Chang was nominated for the Academy Award for Unique and Artistic Production at the first Academy Awards in 1929. It was the only year when that award was presented (It lost to F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans).

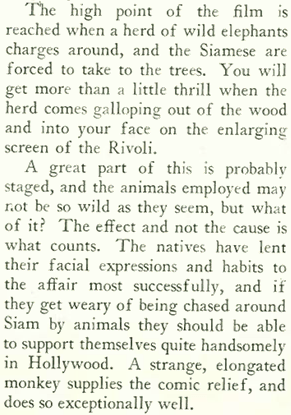

However appalled as we are today by the film’s exploitation of humans and animals alike, those were different times, even for the usually discerning eye of The New Yorker:

In 1927 most people had a very limited view of the non-Western world, which was perceived as both savage and exotic, populated by child-like “natives” who in this case “lent their facial expressions and habits to the affair most successfully…”

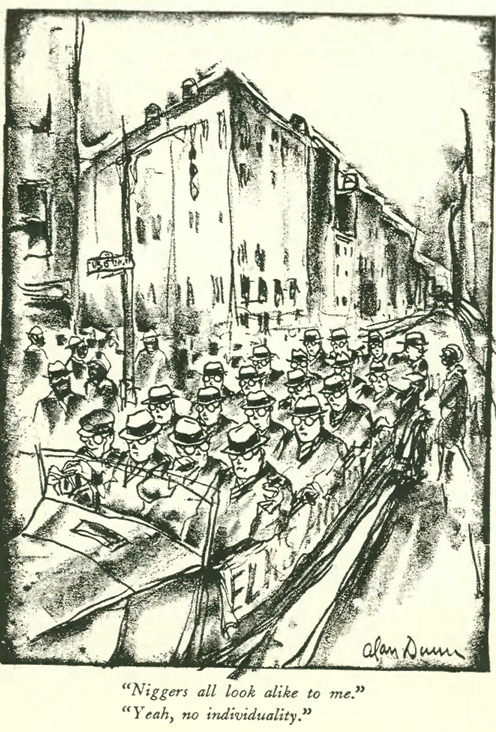

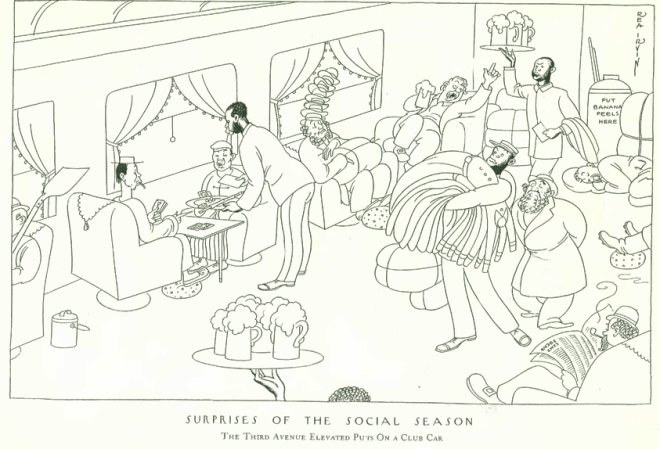

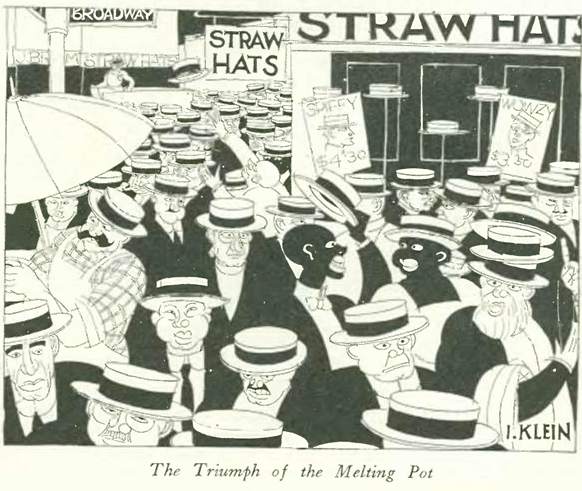

And so in 1927 we also encounter cartoons like this one by Alan Dunn that at once dismisses out-of-town conventioneers (here: an Elks Lodge) as a bunch of ignorant racists, yet the early New Yorker’s own depictions of Blacks were usually minstrel-era stereotypes.

And so in 1927 we also encounter cartoons like this one by Alan Dunn that at once dismisses out-of-town conventioneers (here: an Elks Lodge) as a bunch of ignorant racists, yet the early New Yorker’s own depictions of Blacks were usually minstrel-era stereotypes.

* * *

The massive Graybar Building made its debut at 420 Lexington Avenue, the multi-tiered edifice impressing the “Talk of the Town” editors with the latest technology, including push-button elevators:

* * *

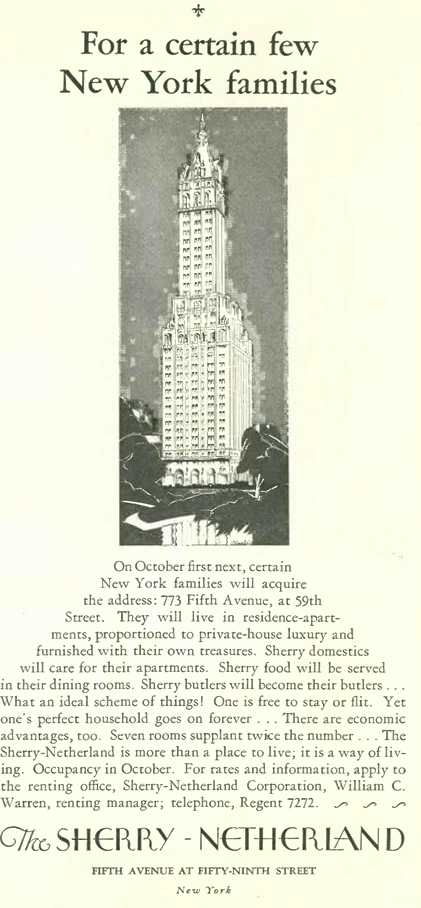

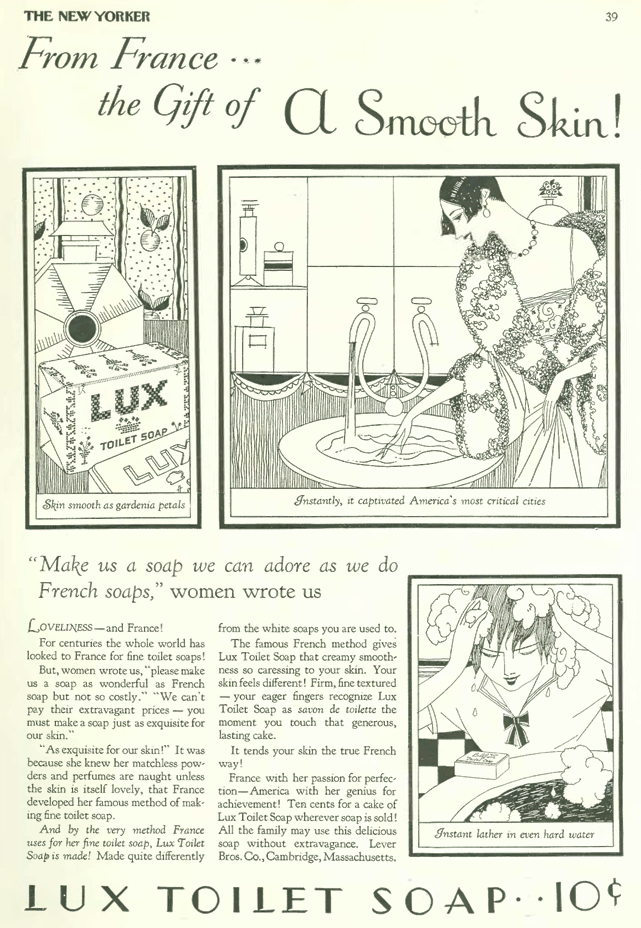

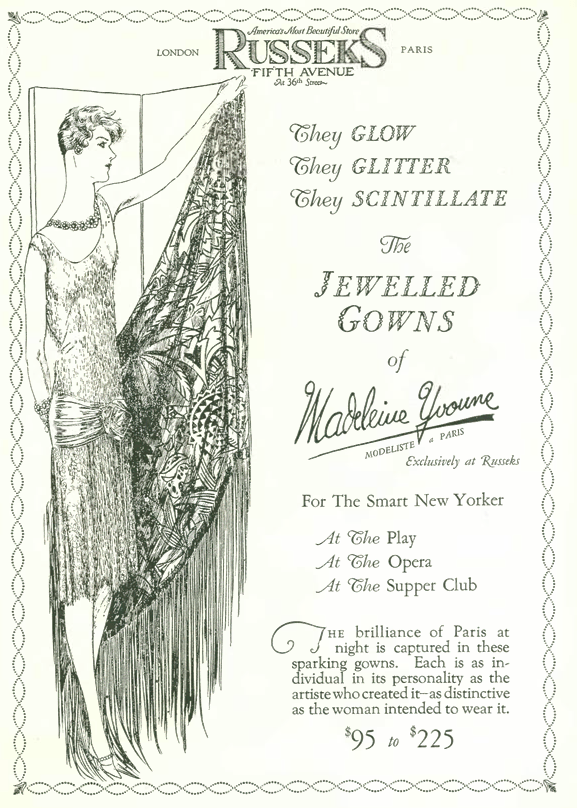

The following advertisement needs some explanation: The 1867 Tenement House Act imposed constraints on height and lot coverage that large apartment buildings routinely violated.

According to an article in the Observer by Stephen Jacob Smith (April 30, 2013), “Some developers got out of these requirements by building co-operative buildings, without rental units, but others wanted to retain the revenue and control that came with rentals, while at the same time building larger structures than the tenement laws allowed. And thus was born the ‘apartment hotel.'”

The New York Times’s columnist Christopher Gray wrote (Oct. 4, 1992) that Apartment Hotels were a “widespread fiction of the period,” and “tenants in fact usually set up full kitchens in the serving pantries.” Smith adds that “one of the reasons apartment hotels were allowed to be built more densely than their fully residential counterparts was that there would be no cooking—a fire hazard in those days—in the units.” An so the ad:

Smith writes that by calling their buildings ‘apartment-hotels,’ builders could claim that as hotels they were outside of the rules of tenement legislation. He notes that “some of Manhattan’s most illustrious buildings were constructed using this legal sleight of hand,” including the Sherry-Netherland on Park Avenue.

The famous scaffolding fire at the Sherry-Netherland, which I featured in my last post, no doubt prompted developers to run the following ad in hopes that people would soon forget about the giant roman candle that burned bright near Central Park on the evening of April 12, 1927.

If you are ever in New York, check out the Sherry Netherland. It is a beautiful building.

And finally, this ad from the makers of Wildroot hair care products. I love the flapper artwork by John Held Jr., and even better the words “CRUDE-OIL SHAMPOO” displayed prominently as a selling point.

Next Time: Mode de Vie…