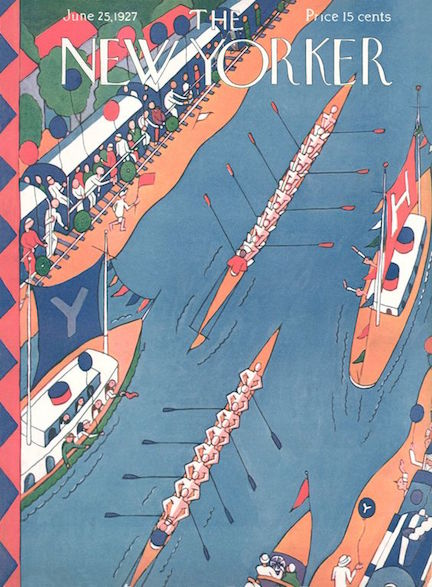

The New Yorker’s founder and editor, Harold Ross, did not approve of office romances. He had a magazine to run after all, and didn’t want any distractions from Cupid’s arrow.

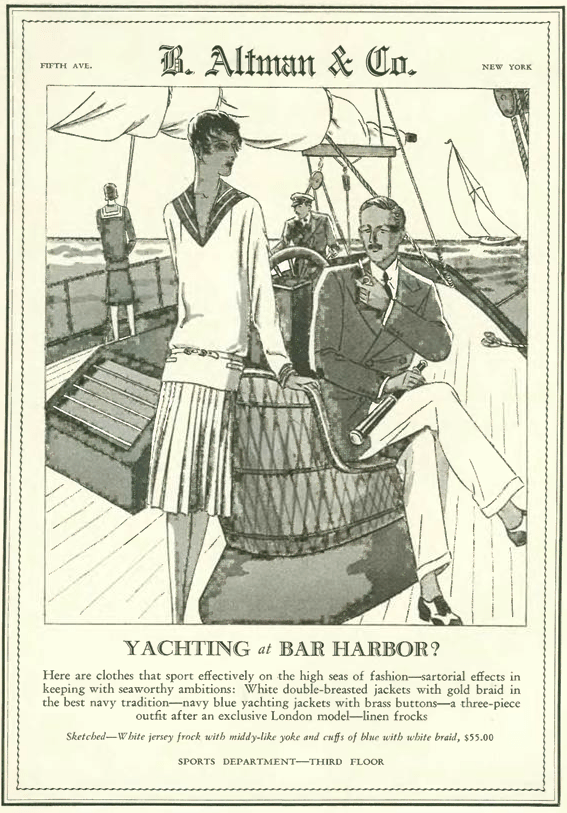

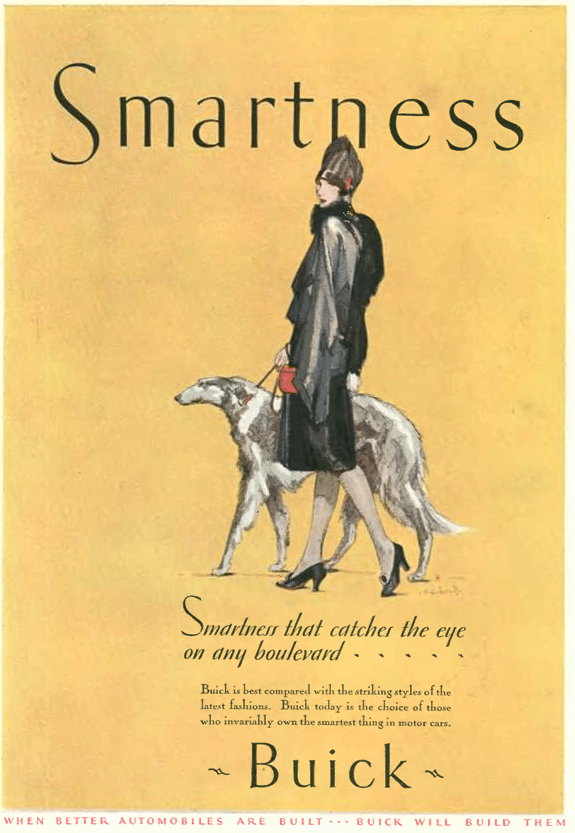

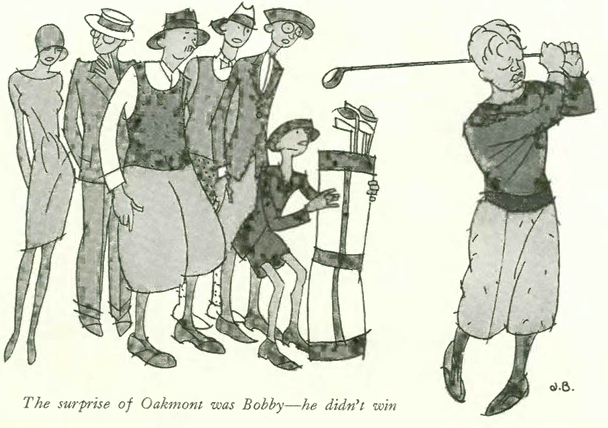

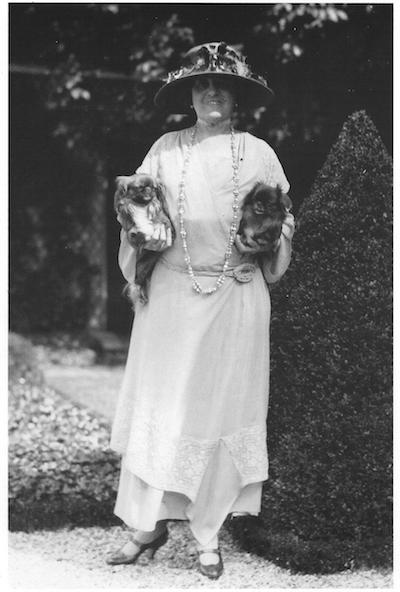

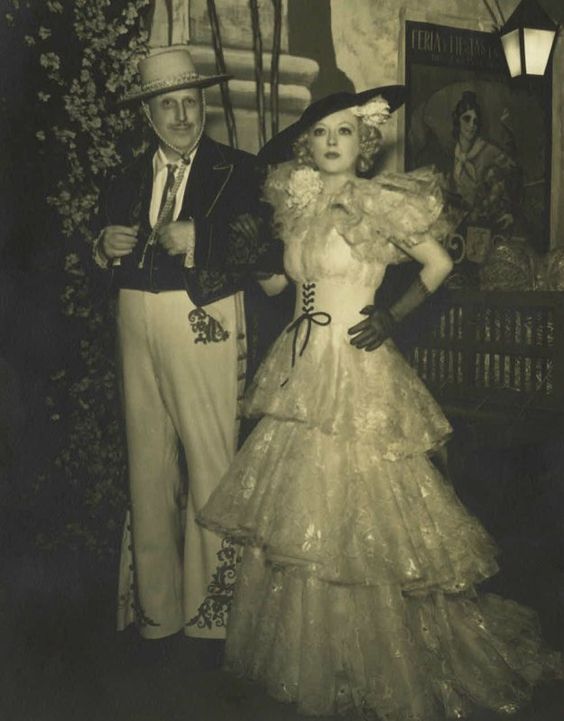

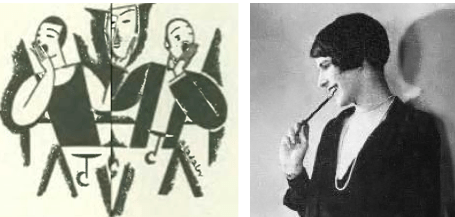

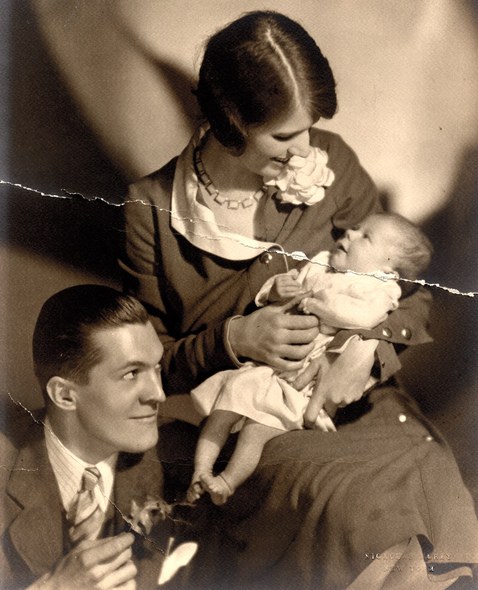

But then again, it seemed inevitable that Lois Long and Peter Arno–two of the magazine’s most lively personalities and important early contributors–would end up together. Arno cut a dashing figure as one The New Yorker’s most celebrated cartoonists. He often drew upon the same subject matter as Long, who covered the nightclub and speakeasy scene in her column, “Tables for Two” and in the process defined the lifestyle of the liberated flapper. Long is also credited with inventing the field of fashion writing and criticism with her other New Yorker column, “On and Off the Avenue.”

In Vanity Fair, Ben Schwartz (“The Double Life of Peter Arno,” April 5, 2016) wrote that Arno and Long “personified what people thought The New Yorker was, which was very fortunate…(Long was) tall, lanky, a Vassar grad with bobbed hair and a wicked sense of humor, a minister’s daughter to Arno’s judge’s son, and she matched him as a hell-raiser.” It was actually their raucous affair that set Ross on a “permanent scowl” regarding office romances.

Schwartz quotes Arno’s and Long’s daughter, Patricia (Pat) Arno, about her parents’ wild relationship: “There were lots of calls to (gossip columnist Walter) Winchell or some other columnist about nightclub fights…with my mother calling and saying, ‘Oh, please don’t print that about us,’ trying to keep their names out of the papers.”

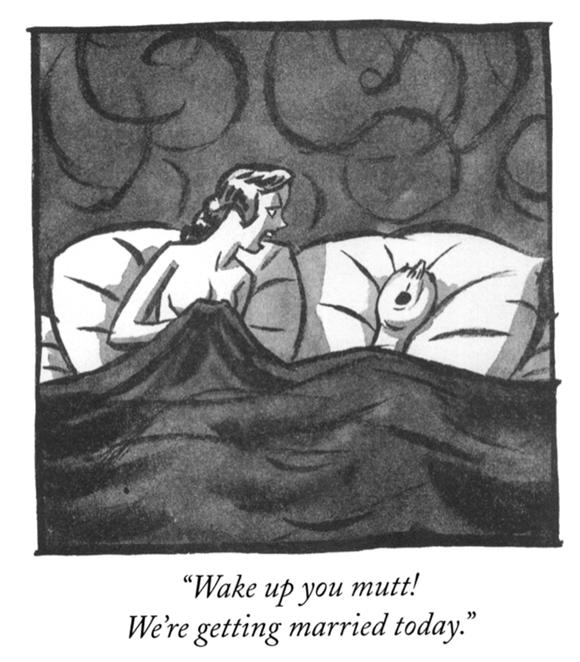

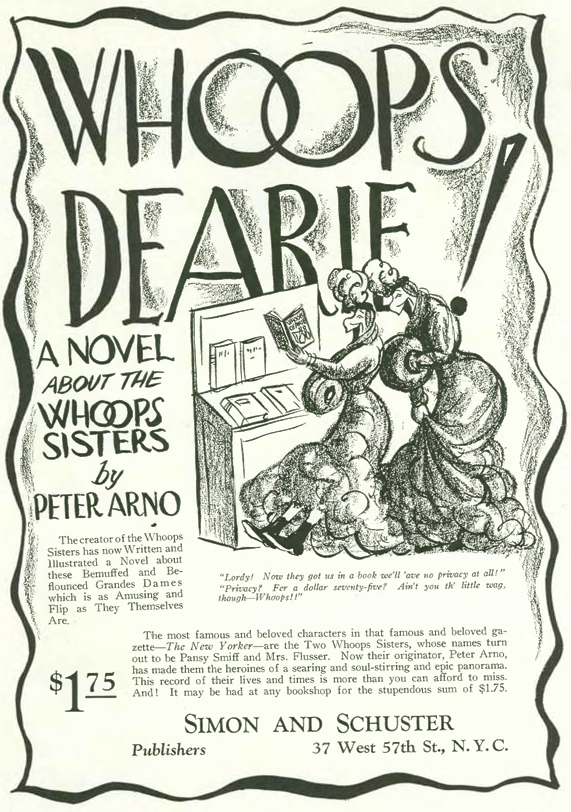

Schwartz suggests that Arno drew on personal experience when in 1930 he published Peter Arno’s Hullabaloo, a “collection of cartoons that included a set of racy drawings featuring a dashing couple much like himself and Long. In one, a nude woman, in bed, yells at her sleeping lover: ‘Wake up, you mutt! We’re getting married to-day.'”

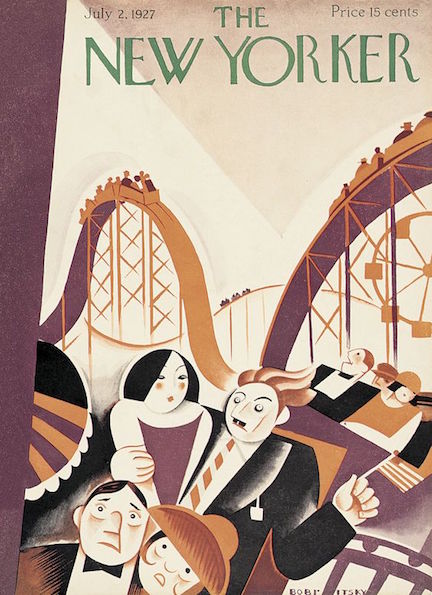

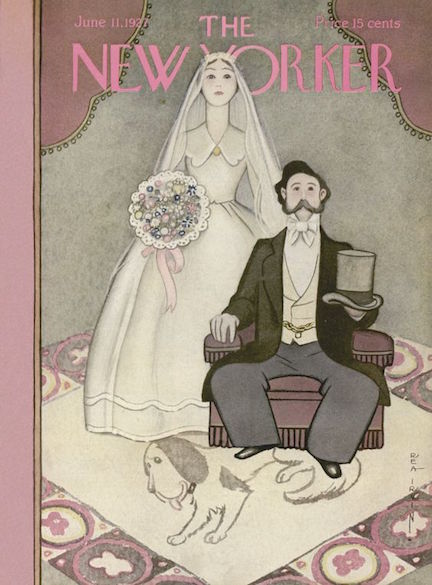

Long and Arno were married by her father, the Rev. Dr. William J. Long, at her parents’ home in Stamford, Conn., on August 13, 1927. Their daughter, Patricia, was born September 18, 1929.

According to Schwartz, Arno’s first three books sold well (Whoops Dearie! 1927, Parade 1929, and Hullabaloo 1930) “allowing the young family to move into an East Side penthouse. Their social circle included New Yorker staffers, the magazine’s owner, Raoul Fleischmann, publishers Condé Nast and Henry Luce, Kay Francis (Broadway actress, future Hollywood star and Long’s former roommate), and some of the city’s financial powers. ‘Once my mother was having trouble with her Plymouth,’ says Pat Arno, “and Walter Chrysler took off his evening coat, rolled up his sleeves, and fixed it himself.'”

Less than two years after the birth of their daughter, Arno and Long would get a divorce in Reno on June 30, 1931. Arno later married debutante Mary Livingston Lansing in August 1935; they divorced in July 1939. After his divorce from Lansing, Arno moved to a farm near Harrison, New York, where he lived in seclusion, drawing for The New Yorker and enjoying music, guns, and sports cars. He died of emphysema on February 22, 1968 at the age of 64.

In 1938 Long would marry Donaldson Thorburn, a newspaper and advertising man. After his death in 1952 she would marry Harold Fox, head of an investment brokerage firm. Long’s colleague at The New Yorker, Brendan Gill, described Fox as “a proper Pennsylvanian named Harold A. Fox.” They lived in an 1807 Pennsylvania-Dutch farmhouse, where Long delighted in the woods, farms and wildlife as well as in her two grandchildren—Andrea Long Bush and Katharine Kittredge Bush. In 1960 she wrote to her alma mater, Vassar College, that the “hectic fifteen years or so after graduation, when I thought I had New York City by the tail and was swinging it around my head, seem very far away. Thank God. I like things this way.” Long would continue working as a columnist for The New Yorker until the death of Harold Fox, in 1968. She died in 1974 at age 72.

* * *

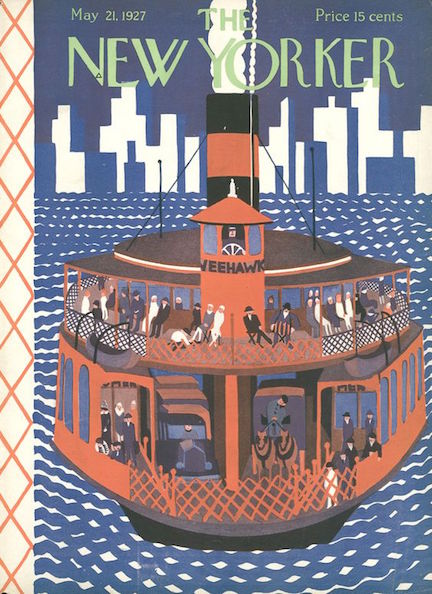

The big news in the Aug. 13, 1927 edition (the same date as the Long-Arno wedding) was President Calvin Coolidge’s brief, ambiguous announcement that he would not run for president. Almost everyone assumed he would run for a second term, given the booming economy in the age of “Coolidge Prosperity.”

Coolidge was summering in Black Hills when he gave his secretary, Everett Sanders, a piece of paper that read, “I do not choose to run for president in 1928.” Sanders then scheduled a midday press conference for August 2, 1927. At 11:30 a.m., Coolidge cut out strips of paper with this statement–I do not choose to run—and at the conference handed each reporter one of the strips. Coolidge offered no further information, and only remarked, “There will be nothing more from this office today.” This led to considerable debate among the press as to intentions of the president. The New Yorker’s “Talk of the Town” mused…

…Howard Brubaker’s “Of All Things” column offered this wry observation…

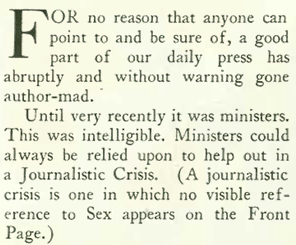

…while humorist Robert Benchley (writing under the pseudonym “Guy Fawkes”) in his “The Press in Review” column continued The New Yorker’s stinging attack on the media for its continued attempts to sensationalize events or impart personality traits on colorless newsmakers:

Next Time: The Movies Take Wing…