Above: Seated in front of a massive Technicolor camera, Rouben Mamoulian directs Miriam Hopkins (also inset) in Becky Sharp, the first feature shot entirely in three-color Technicolor. The film was based on character from William Makepeace Thackeray's 1848 novel Vanity Fair. (UCLA Film & Television Archive)

Rouben Mamoulian’s 1935 production of Becky Sharp wasn’t the first color film, but it was the first feature film to use the newly developed three-strip Technicolor process throughout, setting a standard for color films to come.

Earlier color processes included films that were hand-tinted. Others used various dyes and techniques that included photographing a black-and-white film behind alternating red/orange and blue/green filters, and then projecting them through red and green filters. The inability to reproduce the full color spectrum, among other issues, had many critics dismissing the idea of color films altogether.

Mamoulian was fascinated by the possibilities of color film; by producing (and later directing) the film, he showcased the advancements in Technicolor. Film critic John Mosher had these observations:

Mosher also checked out the latest from Robert Montgomery and Joan Crawford, who exchanged marital banter in No More Ladies, while George Raft went all gangster in Dashiell Hammett’s The Glass Key.

* * *

Astor’s Risk

“The Talk of the Town” paid a visit to the Real Estate Exchange, where Vincent Astor re-acquired the St. Regis Hotel for five million and change. He then sunk another $500,000 (roughly $12 million today) into the hotel to further its luxurious status (including adding air-conditioning). The hotel’s famed King Cole Room and the Maisonette Russe restaurant opened in October 1935. Excerpts:

* * *

School Days

James Thurber recalled his “tough” years at Sullivant School in Columbus, Ohio, in the essay, “I Went to Sullivant.” Brief excerpts:

* * *

Avril en juin

Paris correspondent Janet Flanner gave a rundown on the latest happenings, including the Toulouse-Lautrec costume ball that attracted none other than Jane Avril, the famed French can-can dancer of the 1890s who could still kick up her heels. Flanner gave Avril’s age at 80, but records indicate she was closer to 70.

* * *

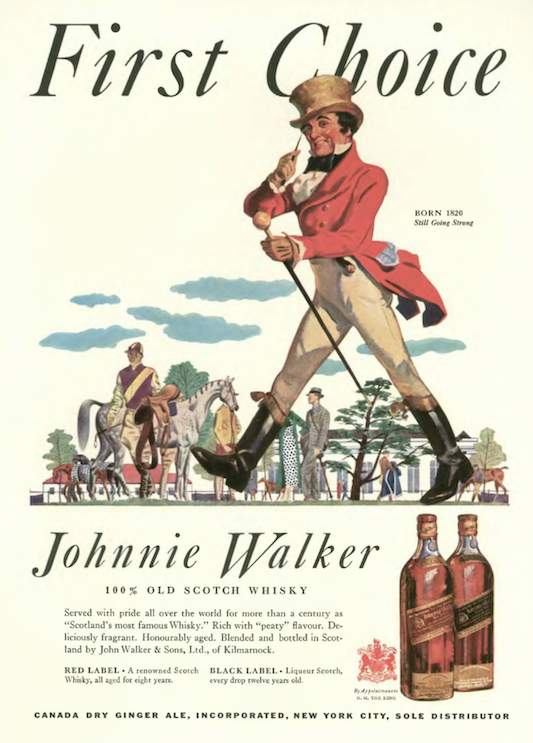

From Our Advertisers

We begin with the inside front cover, Johnnie Walker strutting along at the horse races…

…the inside back cover belonged to Arrow Shirts…

…and no surprise that the back cover featured a stylish woman enjoying a cigarette, in this case a Lucky…

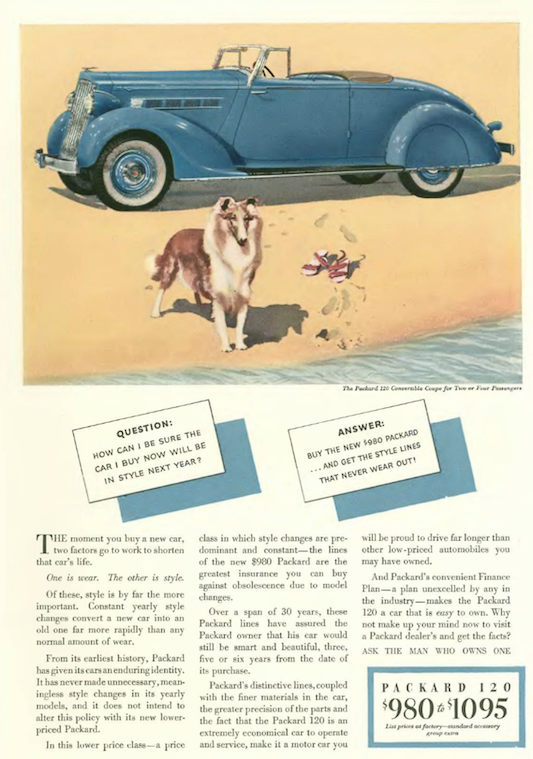

…Packard continued to run these colorful, wordy ads that made the case for owning a lower-priced Packard, which I’m sure was a fine automobile…

…John Hanrahan, who early on served as The New Yorker’s policy council and guided it through its lean first years, became the publisher of Stage magazine (formerly The Theatre Guild Magazine) in 1932. In 1933 Stage became part of the Ultra-Class Magazine Group’s line-up that included Arts & Decoration and The Sportsman. Stage published its last issue in 1939, and I don’t believe the other two survived the 1930s either…this Mark Simonson site looks at the striking design elements of an issue from 1938…

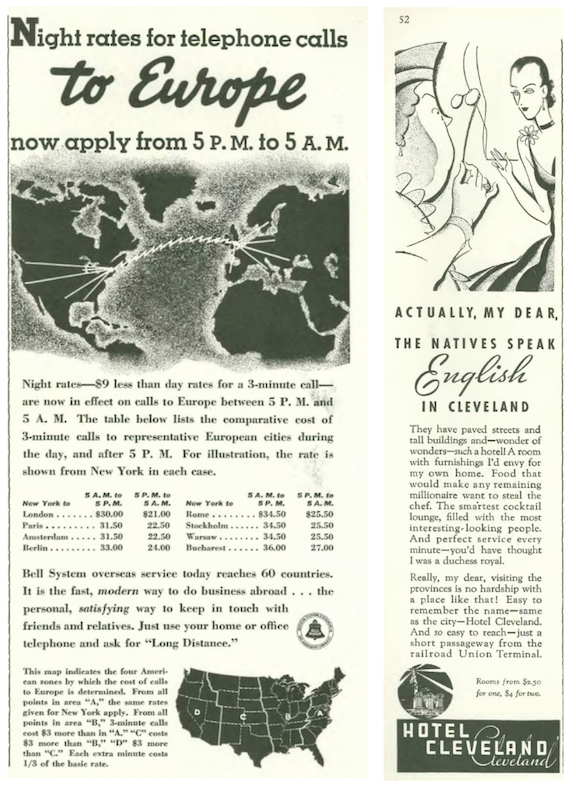

…a couple from back of the book…calling Europe by telephone in 1935 was an impressive feat, however it could cost you roughly $700 in today’s dollars to make a three-minute call to London…the one-column ad at right offered an Anglophilic appeal to those visiting Cleveland…

…this simple spot for Dole pineapple juice caught my eye because it was illustrated by Norman Z. McLeod (1898–1964), who drew Christie Comedy title cards during the Silent Era…

McLeod was also an acclaimed director of Marx Brothers comedies Monkey Business (1931) and Horse Feathers (1932), W.C. Fields’ It’s a Gift (1934), Danny Kaye’s The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (1947) and two of the Topper films.

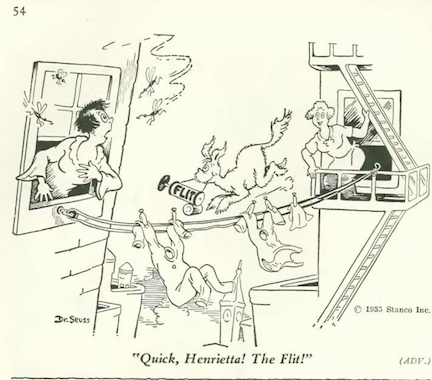

…Dr. Seuss was back with his Flit advertisements…

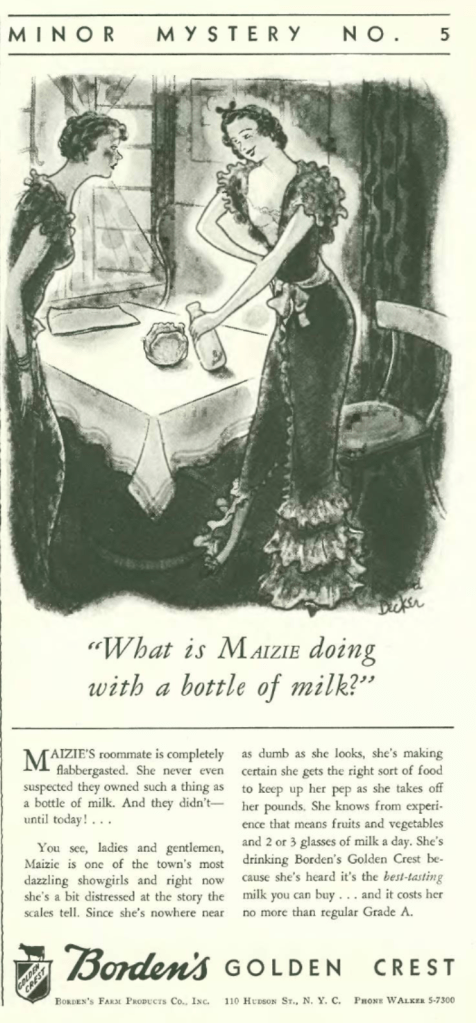

…Richard Decker illustrated this ad for Borden’s “Golden Crest” Farm Products…

…which segues into our cartoonists, and this curious spot drawing by James Thurber…

…Perry Barlow gave us the early days of the “Bed and Breakfast”…

…Peter Arno, and no rest for the titans of industry…

…Gluyas Williams continued to take a sideways glance at Club Life in America”…

…from George Price…back in the day, tattoos were usually confined to sailors and longshoreman…this particular fellow found himself with some outdated ink…

…Kemp Starrett took us ringside…

…Mary Petty reflected on a bit of narcissism…

…and we close with William Steig, and mixed feelings about the summer season…

Next Time: Happy Motoring…