The death of artist Claude Monet prompted the editors of the New Yorker’s “Talk of the Town” to speculate on the true origins of the “Impressionist” movement of the late 19th century.

Note how the “Talk” editors lightly regarded the artist’s late period, during which he painted his famous “Water Lilies” series:

The editors also used the occasion to clear up the confusion (in the lay mind) between Édouard Manet and Monet, identifying them not only as two distinct persons but also crediting the former with the founding of the Impressionism technique while giving Claude his due for actually giving it a name:

Another much younger notable of the age, Ernest Hemingway, was the talk of literary society on both sides of the Atlantic with the publication of his latest novel, The Sun Also Rises. According to the New Yorker’s Paris correspondent Janet “Genêt” Flanner, the novel was creating a buzz in Montparnasse over the origins of the book’s colorful characters:

Keeping in mind that the Christmas shopping season was still in full swing, Frigidaire thought it the perfect time for New Yorker readers to buy a newfangled electric refrigerator:

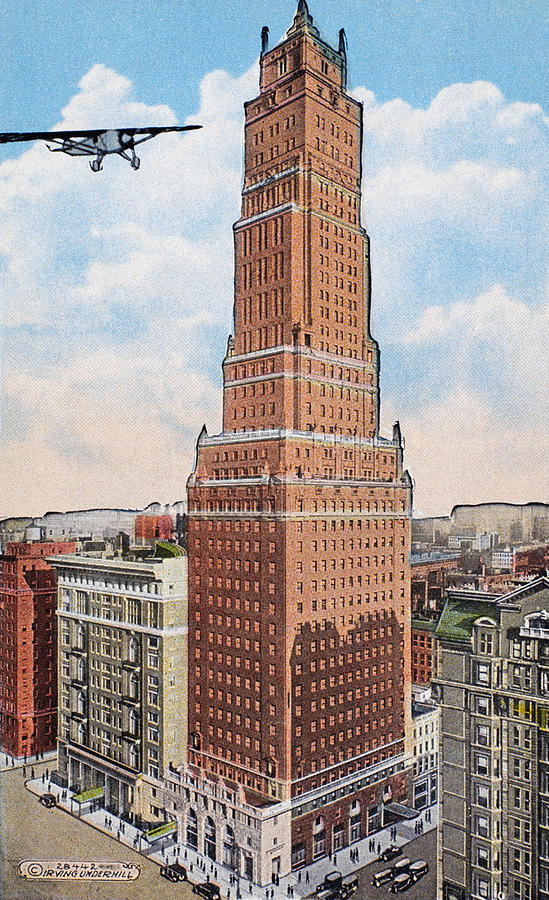

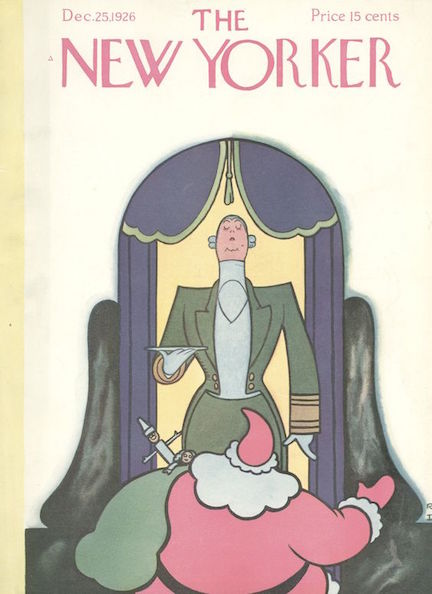

And we ring out the year with the final issue of 1926:

It was a tough year for New Yorker film critic “OC”, who summed up his disappointment with the movies by offering a Top Ten list that included only two films:

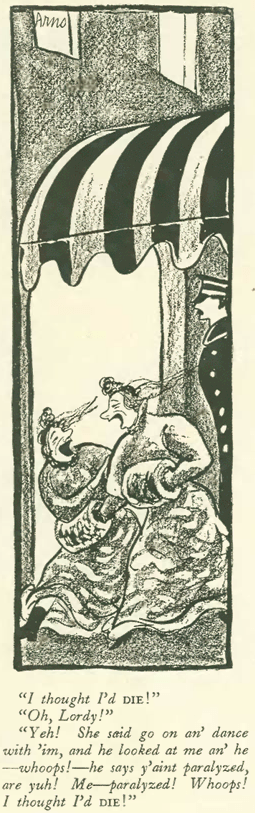

And to close, this cartoon by Helen Hokinson, which in the original magazine filled all of page 14 and therefore had to be printed sideways:

Next Time: 1927-A Year to Remember…