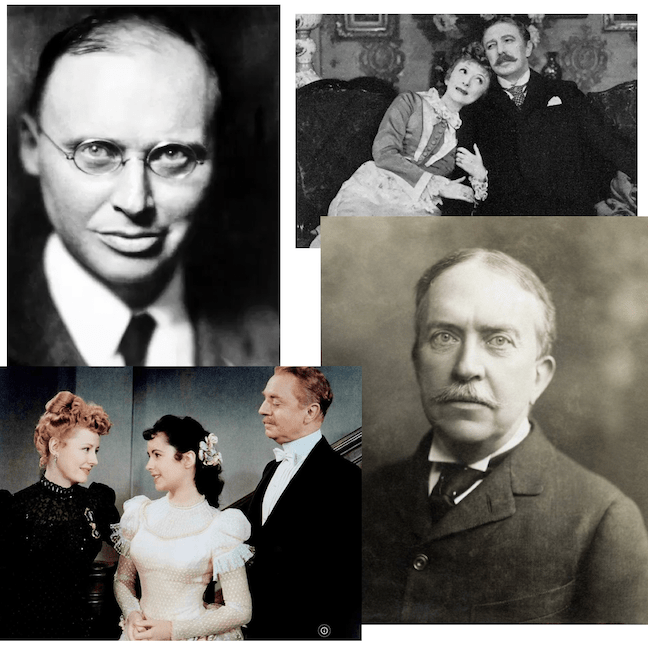

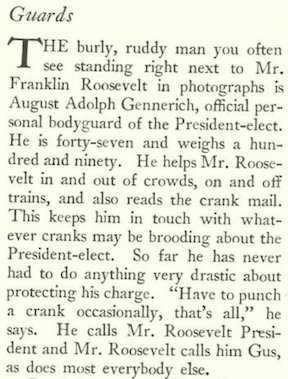

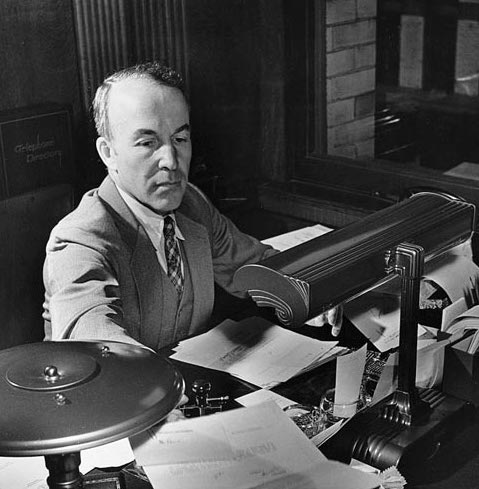

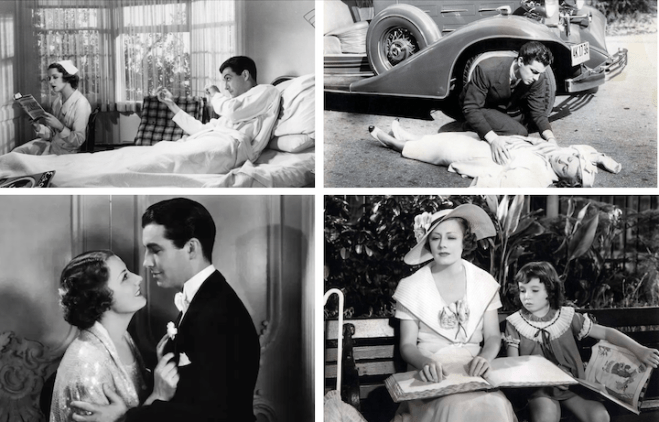

Above: Irene Dunn gets her head examined by Parisian doctors during a scene from the 1935 melodrama Magnificent Obsession. (letterboxd.com)

I can’t think of a better time to escape the world for a few moments and indulge in a bit of frivolity. In this case we take a brief look at a popular film that pushed the envelope of plausibility in true Hollywood style.

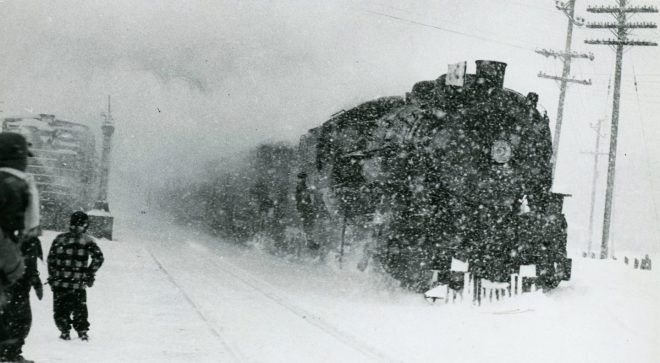

Magnificent Obsession featured two of Tinseltown’s leading stars, Irene Dunn and Robert Taylor. Although many critics have called the film’s plot preposterous, it was a fan favorite—at the Radio City Music Hall premiere on Dec. 30, 1935, capacity crowds braved sub-zero weather to see it.

For a film that has been debated and discussed for decades (and remade to some acclaim in 1954 by director Douglas Sirk with Jane Wyman and Rock Hudson in the leads), critic John Mosher barely gave it a glance, feeling sorry for Dunne in her role as a tragically blinded widow.

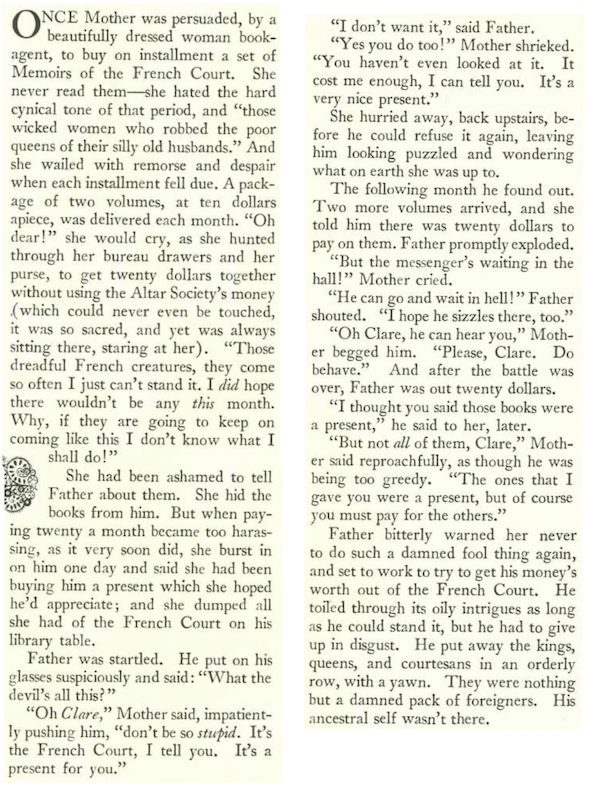

A brief synopsis: Wealthy playboy Robert Merrick (Robert Taylor) drunkenly capsizes his boat. A hospital’s only pulmotor saves his life at the expense of a beloved surgeon who dies without it. Merrick falls in love with the surgeon’s widow, Helen (Irene Dunn). While driving Helen home he makes a pass at her; she exits the car and is struck by another, losing her eyesight. Merrick conceals his identity while watching over Helen; he then follows her to Paris, where she learns her sight is gone forever. Merrick reveals his identity and proposes. Helen flees. Six years later Merrick, now a Nobel Prize-winning brain surgeon, restores Helen’s sight.

In the film’s defense, plots that stretch credibility have been around since the Greeks and deus ex machina, and consider how many films today employ “portals” of various types to get heroes out of sticky situations. Unless you’re talking about a Werner Herzog film, it’s all make believe.

* * *

A Lot On His Mind

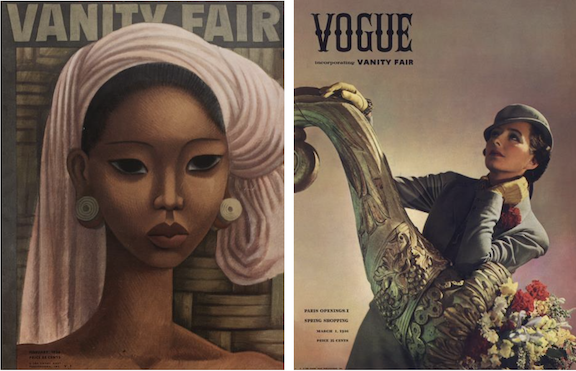

E.B. White had a lot to say in his Jan. 11 “Notes and Comment,” beginning with a paragraph about the impending merger of two Condé Nast publications, Vanity Fair and Vogue. The old Vanity Fair magazine, published from 1913 to 1936, was a casualty of the Great Depression, and it essentially disappeared with the merger (Condé Nast revived the title in 1983).

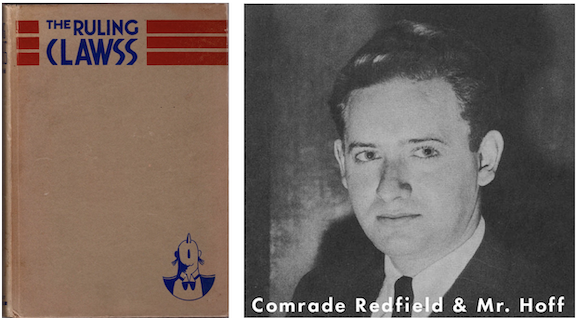

White also commented on a new book, The Ruling Clawss, which criticized The New Yorker for its “bourgeois attitude.” Interestingly, the book was produced by none other than New Yorker cartoonist Syd Hoff, who wrote and illustrated The Ruling Clawss as “A. Redfield,” a pseudonym he used in the 1930s for his contributions to The Daily Worker and other leftist causes.

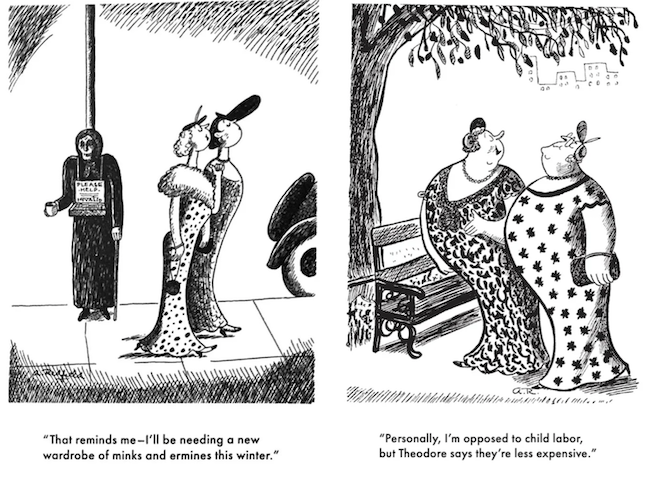

In The Ruling Clawss, Hoff (as Redfield) criticized “bourgeois humor” as an opiate of the masses, citing The New Yorker, Esquire, Judge, and Life as publications that take “the banker boys and politicians, who are the rapers of liberty and democracy,” and present them between perfume ads in whimsical situations. The bourgeoisie makes itself look human, wrote Hoff, “By exposing itself in the boudoir, or the night club, doing foolish things or saying something ‘funny’…In other words, the fascists and warmongers are little lambs who do their parts in contributing to the merriment of a nation.”

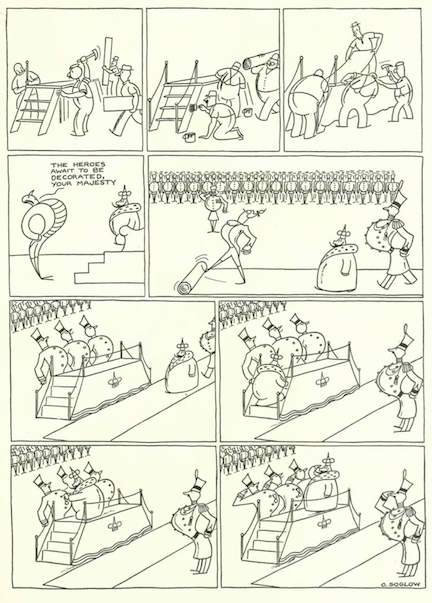

Referring to his fellow cartoonists, Hoff concluded: “the Arnos, Soglows, Benchleys and Cantors…are all talented and funny, but…and here, I believe, is the point…their comedy is all too often a whitewash for people and conditions that, in reality, are not funny.”

Today Hoff is probably best remembered for his children’s books, especially Danny and the Dinosaur. You can read all about his work at this website.

* * *

A Different Kind of Hoff

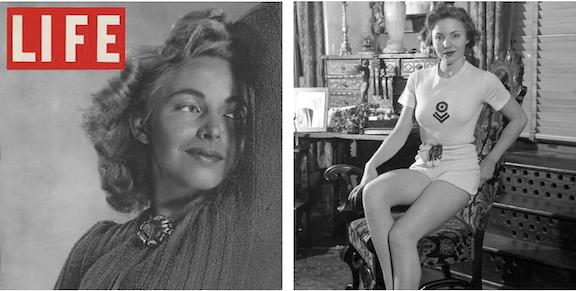

We move on to another Hoff, namely Mardee Hoff, who was “ungrammatically selected” by the American Society of Illustrators as the possessor of the “most perfect figure in America.” Here is an excerpt from “The Talk of the Town.”

* * *

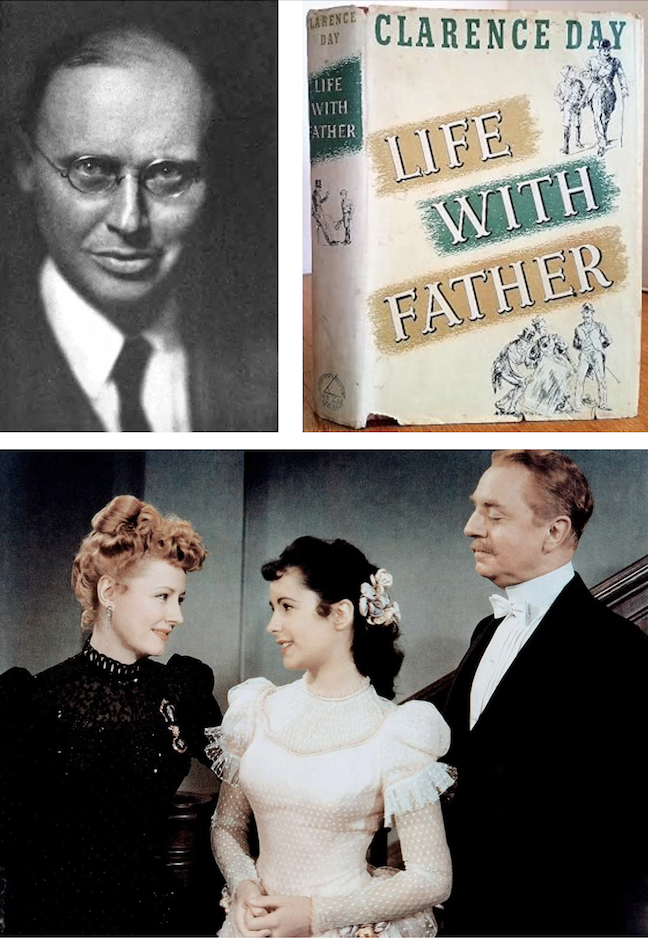

Life With Clarence

“The Talk of the Town” noted the passing of beloved author and cartoonist Clarence Day in a lengthy tribute that highlighted his remarkable output despite crippling arthritis. Excerpts:

* * *

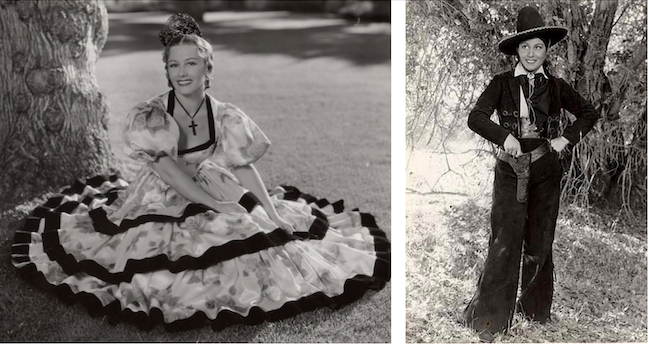

…Mosher thought the best thing about mezzo-soprano Gladys Swarthout in Rose of the Rancho was her, um, feet…

…and he was frankly mystified by the Soviet Russian film Frontier, featuring lots of beards, collective farms, and a big display of airplanes at the finale…

* * *

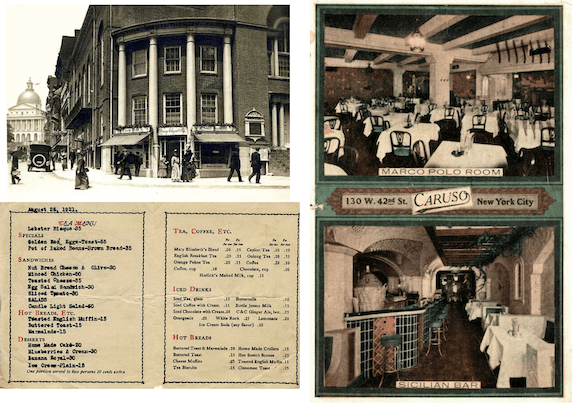

From Our Advertisers

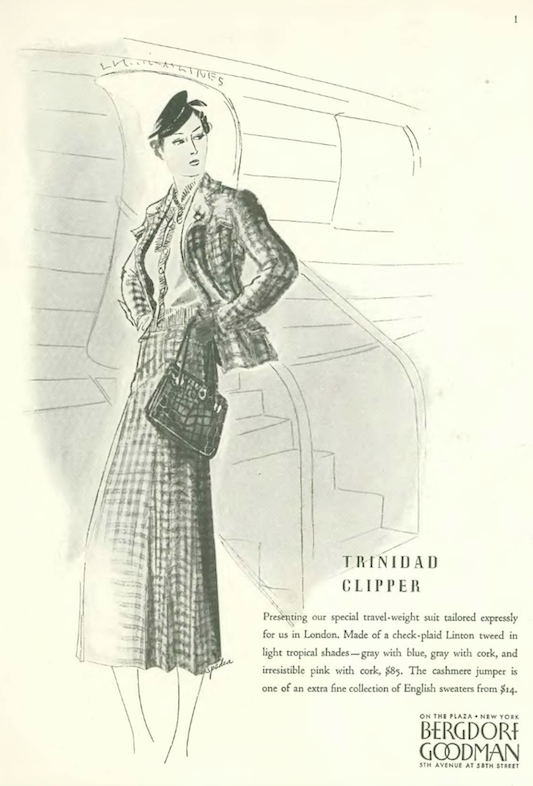

We take wing with Bergdorf Goodman’s stylish “Trinidad Clipper suit…

…the folks at Nash took out the center spread to tout their inexpensive yet distinguished Ambassador…

…apparently it was distinguished enough for these toffs…

…by contrast, a more spare, minimal style is seen in this ad for Schaefer beer…

…and in this ad for Bloomingdale’s…this was tricky to reproduce, the lightness of the compass against all that black ink…

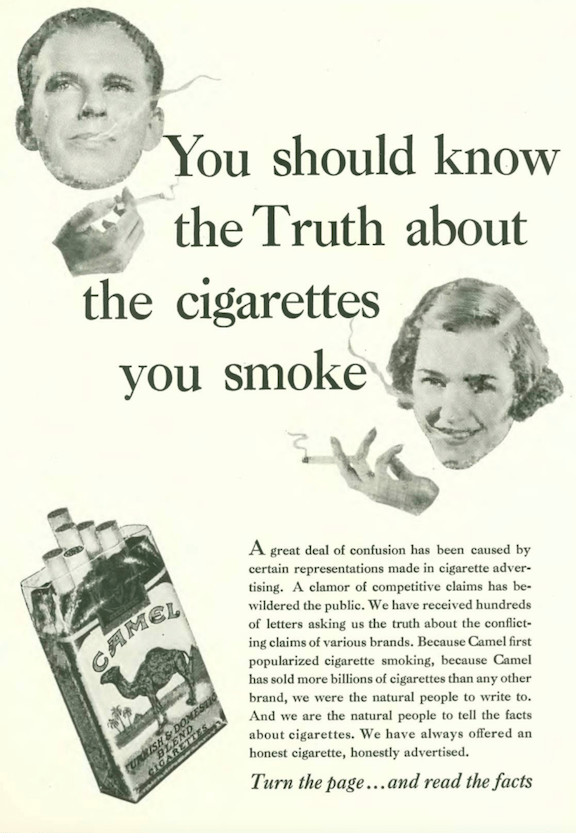

…here’s a new marketing ploy from R.J. Reynolds…smoke a half a pack of their Camels, and then send back the rest if you don’t like them…I’m guessing most folks finished them off…

…Liggett & Myers kept it simple, equating smoke in your lungs with clean, crisp winter air…

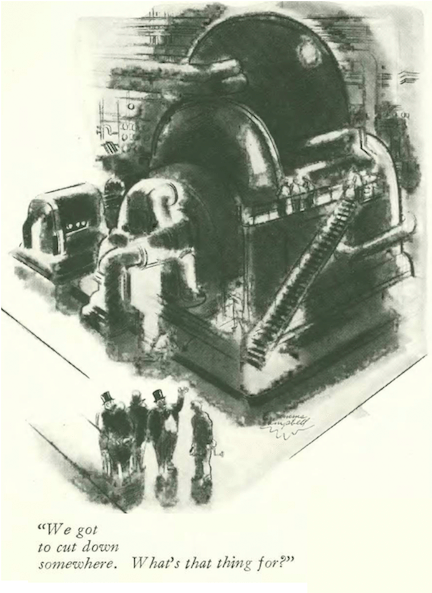

…on to our cartoonists, we begin with spots by Gregory d’Alessio…

…Daniel “Alain” Brustlein…

and Christina Malman…

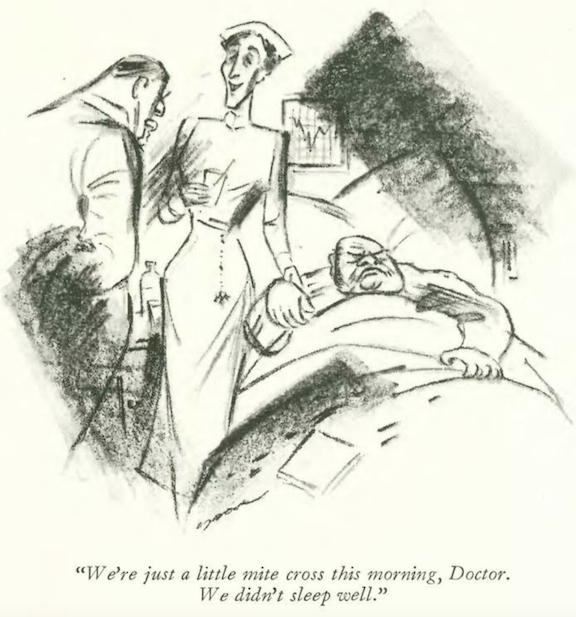

…Leonard Dove looked in on an owly patient…

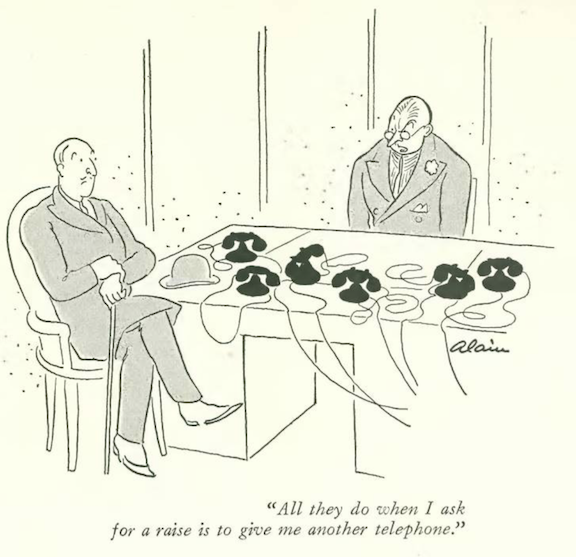

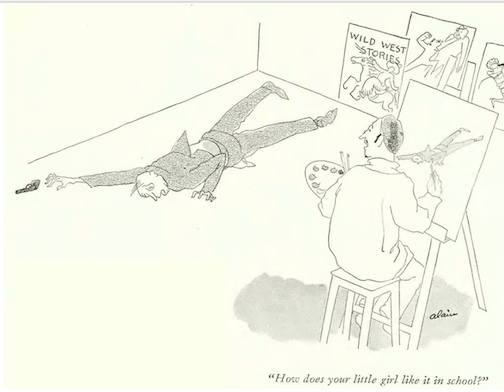

…Alain again, seeking an elusive promotion…

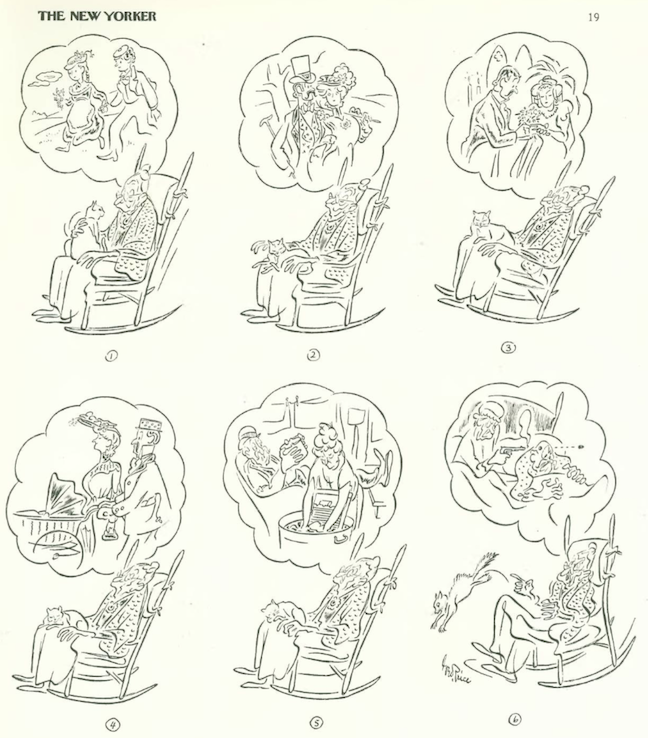

…the stages of love and marriage, per George Price…

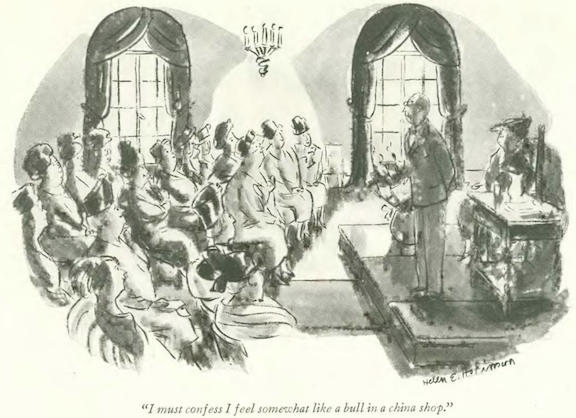

…Helen Hokinson reconvened her ladies club…

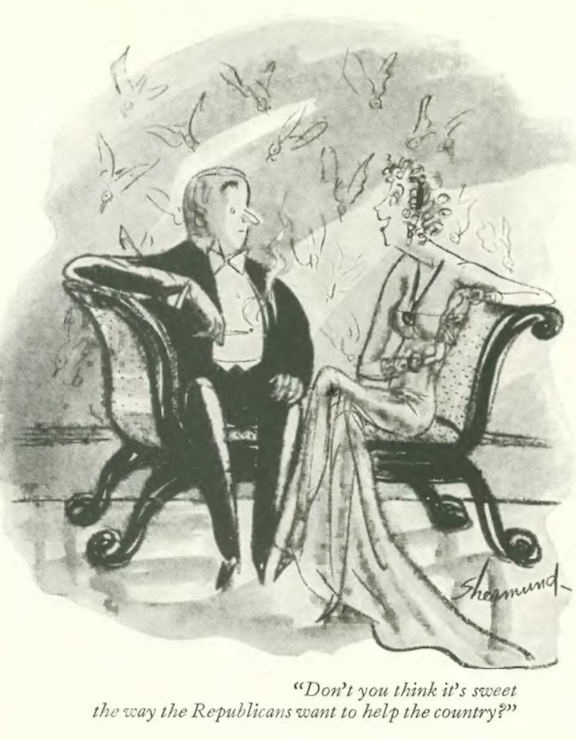

…Barbara Shermund discussed politics…

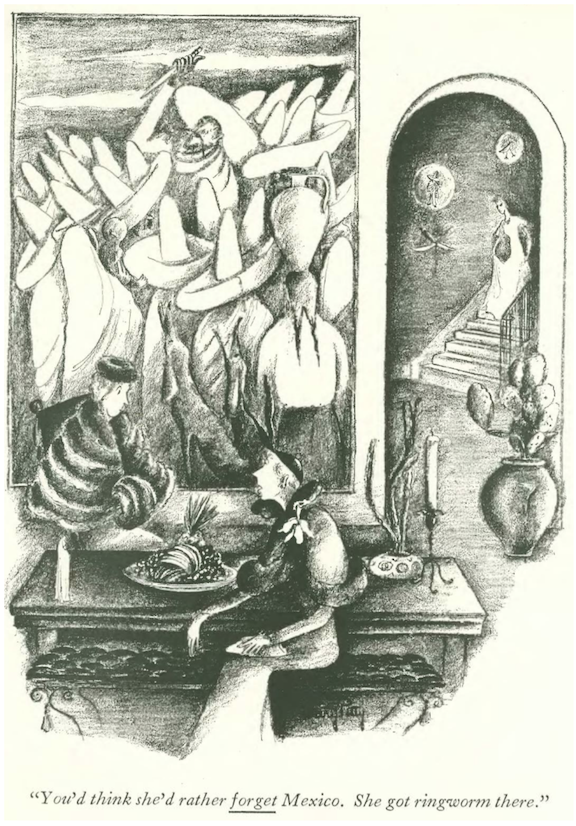

…Mary Petty considered the price of great art…

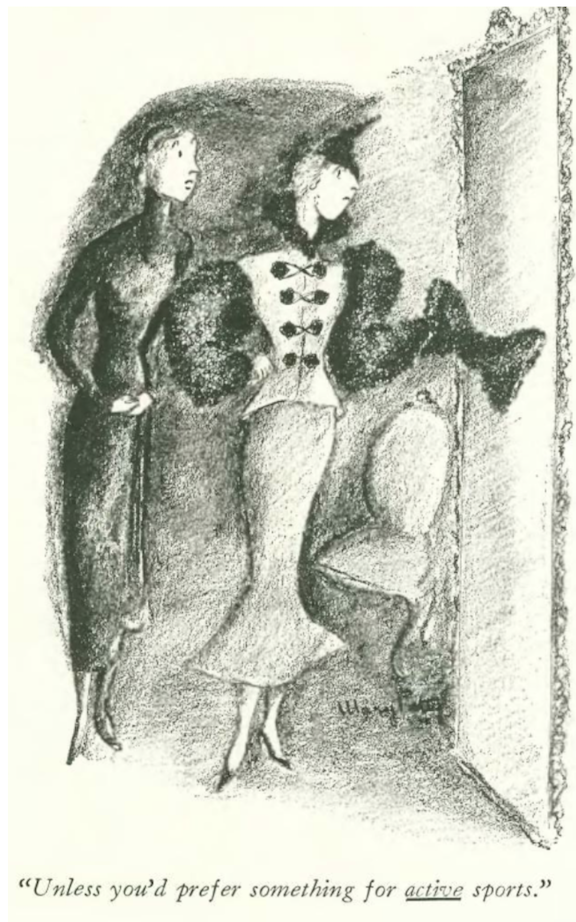

…and Petty again, at the dress shop…

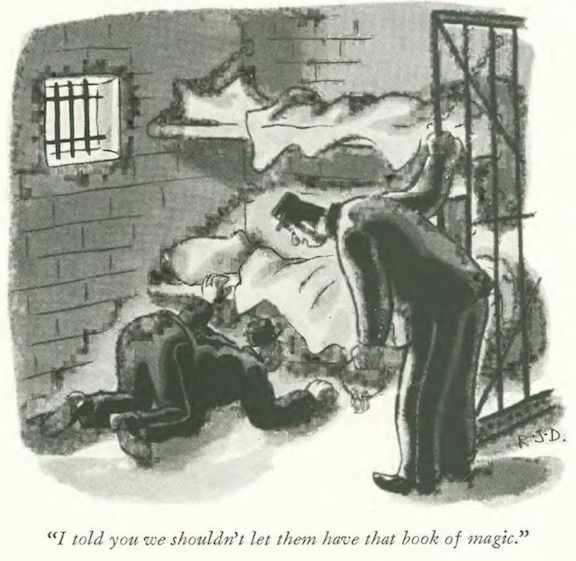

…Robert Day illustrated the benefits of “how to” books…

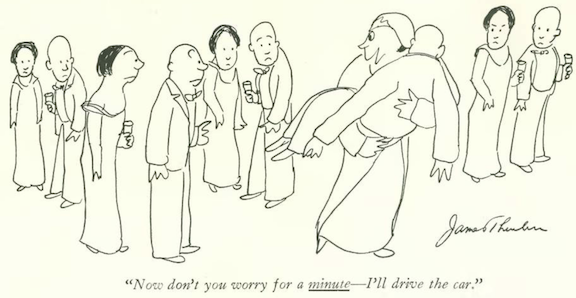

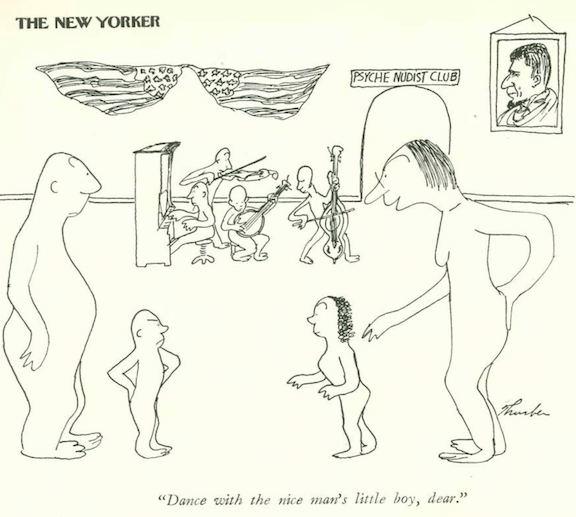

…and we run off with James Thurber...

Next Time: A Profile in the Paint…