ABOVE: E.B. White presented us with a mixed bag of February happenings, from the comings and goings of Neily Vanderbilt to the Macon disaster and the economic power of Mickey Mouse.

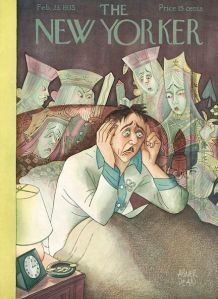

The title for this entry comes from E.B. White’s “Notes and Comment” column, which kicked off the Feb. 23, 1935, issue with a quick rundown of February events.

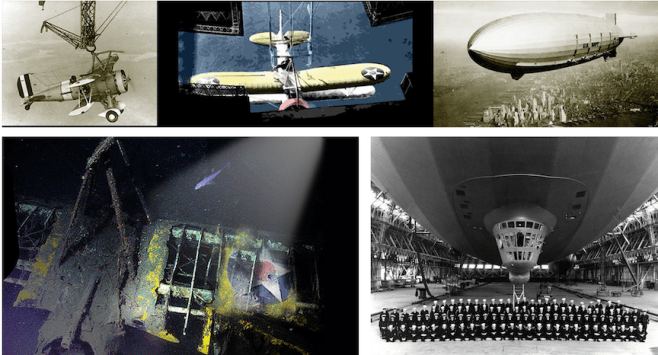

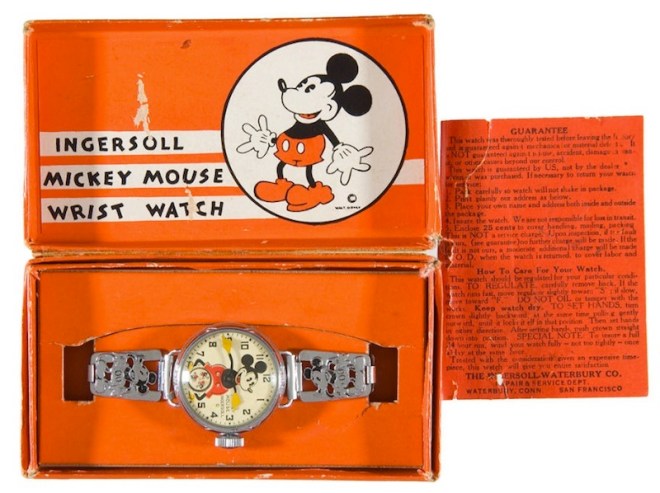

February notably marked the end of the Bruno Hauptmann trial. Convicted of the abduction and murder of the infant son of Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh, Hauptmann would go to the electric chair on April 3, 1936. White also noted the return of Admiral Richard Byrd from his second Antarctic expedition, the demise of the U.S. Navy airship U.S.S. Macon, and the economic miracle of the Mickey Mouse watch.

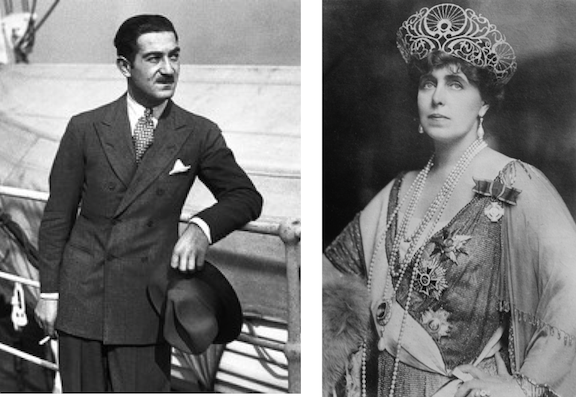

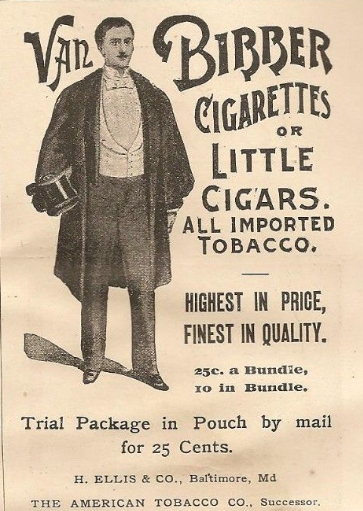

White also made note of the comings and goings of Cornelius “Neily” Vanderbilt III (1873–1942), who was saying farewell to Fifth Avenue (although he would return to live out his life there), while New Yorkers were apparently saying farewell to the Park Avenue Tunnel (aka Murray Hill Tunnel). After more than 190 years it is still there, now serving a single lane of northbound traffic from 33rd to 40th Street.

* * *

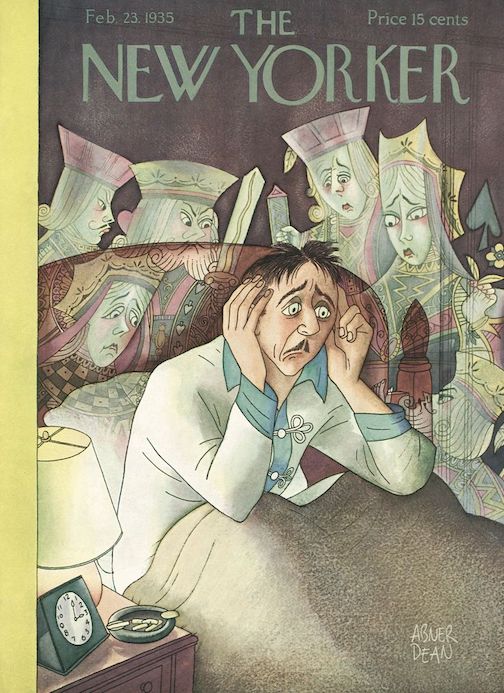

Getting An Earful

Howard Brubaker, in his column “Of All Things,” made this observation of deepening repression taking place in Nazi Germany…

* * *

Try Our Knockout Cheesecake

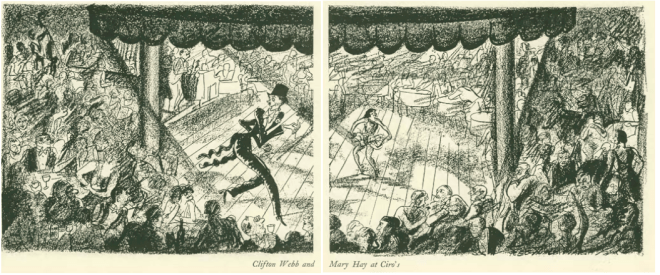

Lois Long continued her chronicle of New York night life, in this excerpt making note of the celebrity gawkers at Jack Dempsey’s tavern/restaurant near Madison Square Garden. Apparently Dempsey’s place was renown for its cheesecake…

* * *

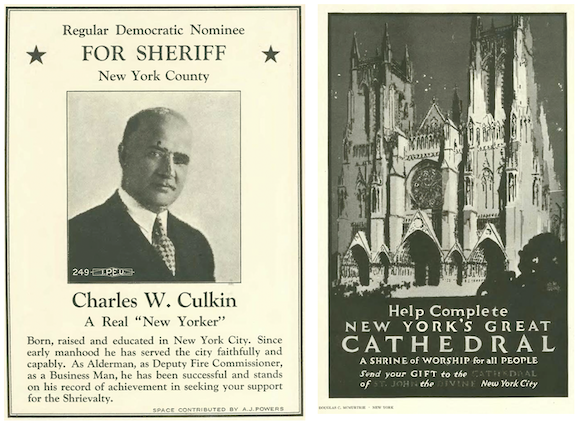

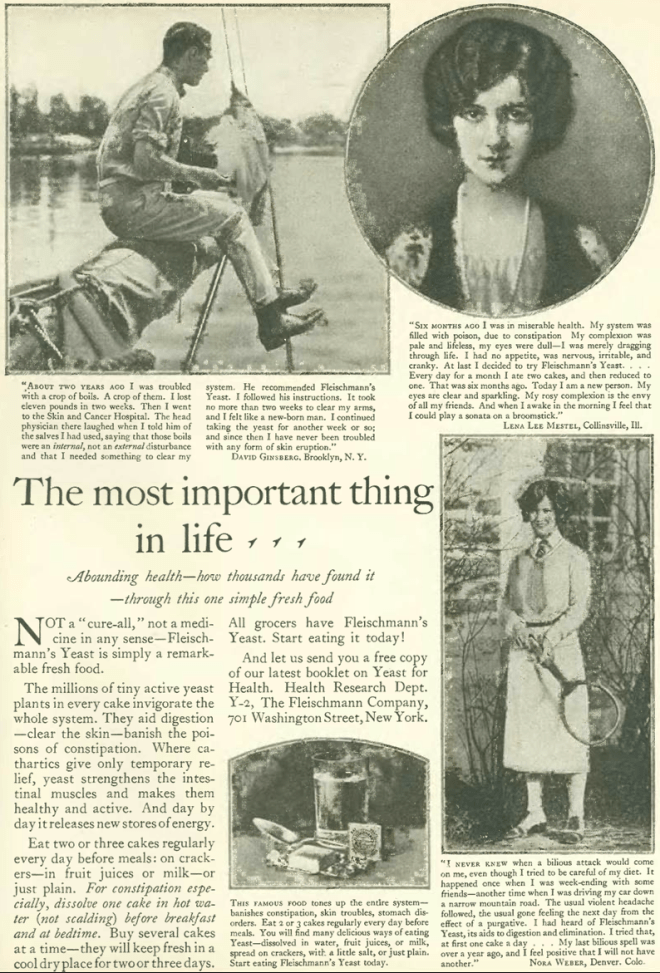

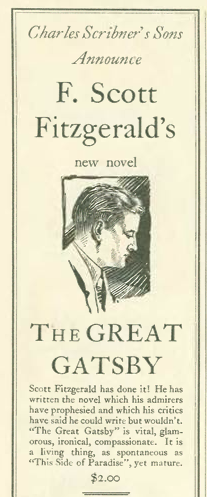

From Our Advertisers

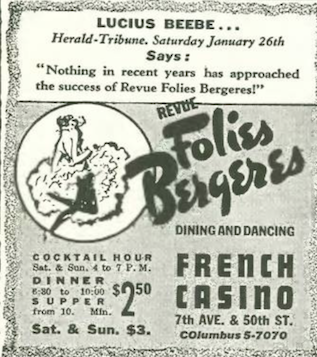

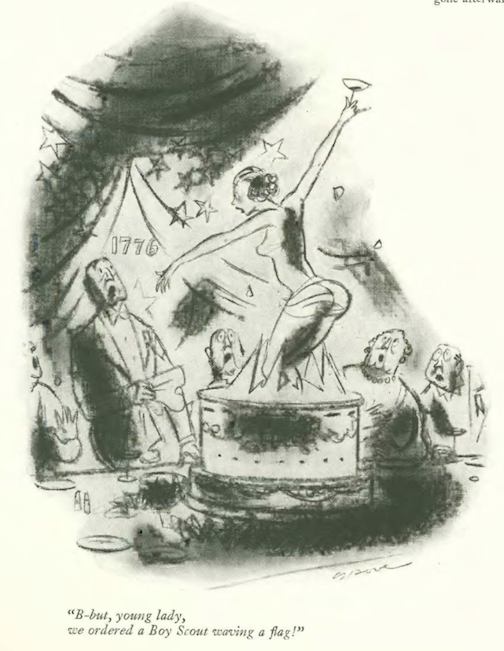

The refurbished Earl Carroll Theatre (7th Ave. and 50th St.) opened as the French Casino late in 1934. The art deco theatre’s first show was the Revue Folies Bergères, promoted here in this small ad on page 54 in the Feb. 23 issue…

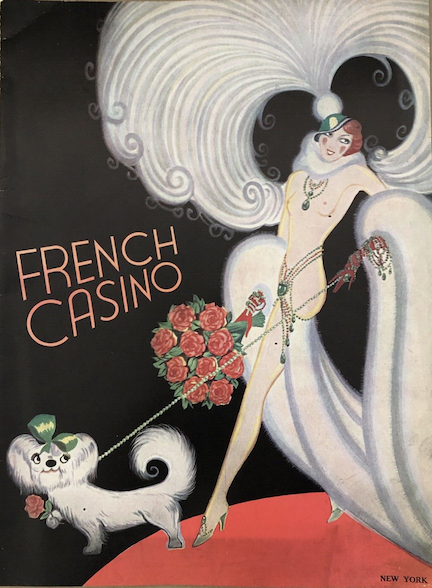

…the menu’s cover suggests patrons weren’t there for the cheesecake (yes, there is a pun, but I’m not touching it)…

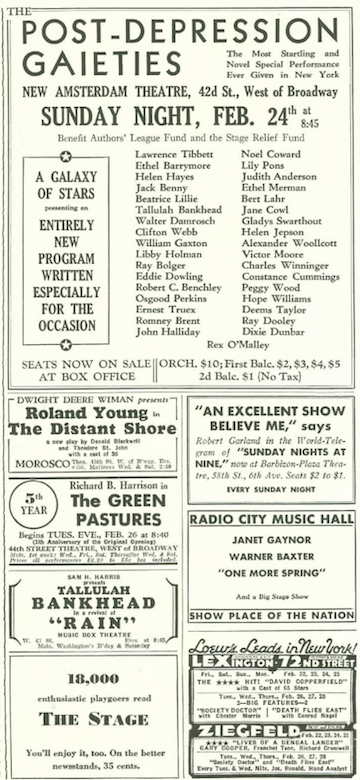

…another ad in the back pages touted the “Post-Depression Gaities” at the New Amsterdam Theatre with an impressive roster of stars including New Yorker notables Robert Benchley and Alexander Woollcott…

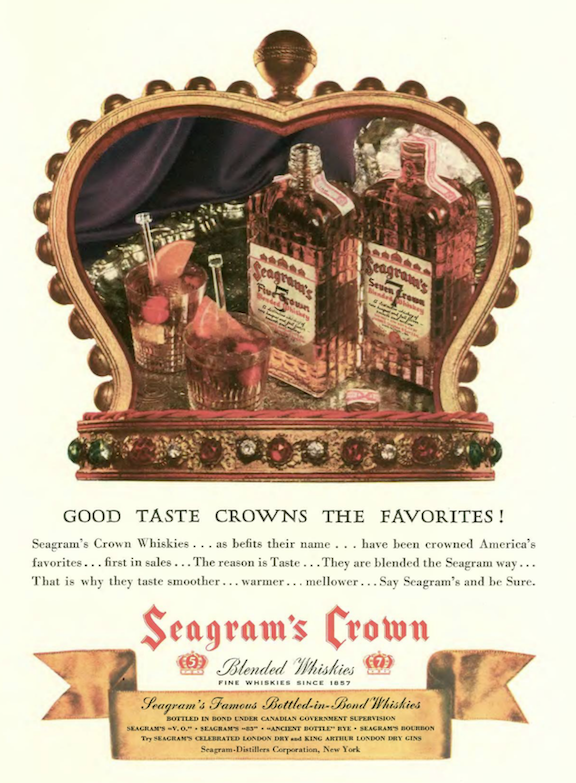

…following Prohibition, Seagram introduced two blended whiskies—5 Crown and 7 Crown. Seagram 5 Crown was discontinued in 1942, while Seagram 7 would go to become the first million case brand in U.S. history…

…this one-column ad caught my eye for the rendering of the stereotypic ill-tempered matron, here having a fit over tomato juice…

…coming from an old and influential New York family, it’s hard to believe Elizabeth West Post Van Rensselaer thought about Campbell’s soup when her daughter, Elizabeth, fell seriously ill…at any rate, something must have worked because her daughter lived until 2001…

…For a time “Chief Pontiac” served as a logo for the Pontiac line of automobiles, discontinued by GM in 2010…

…many automobile advertisements of this era emphasized safety, none more prominent than the “Body by Fisher” ads that frequently featured happy little children…oddly, no one had yet considered seat belts, car seats or other safety measures we now take for granted…

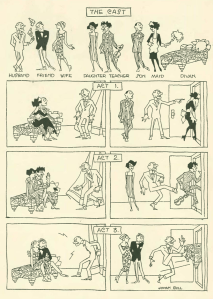

…the makers of Old Gold cigarettes (Lorillard) ran a series of ads featuring a sugar daddy and his leggy mistress…they were drawn by George Petty (1884–1975), famed for his “pin-up girls”…as an added bonus below the ad, you could renew your New Yorker subscription—two years for seven bucks…

…the makers of Camels kept it classy with their continuing series of society women enjoying their unfiltered “Turkish & Domestic” blend…

…the “young matron” in the ad, the Sydney, Australia-born Joan (Deery) Wetmore (1911-1989), was indeed “much-photographed,” and was a favorite of Vogue photographer Edward Steichen:

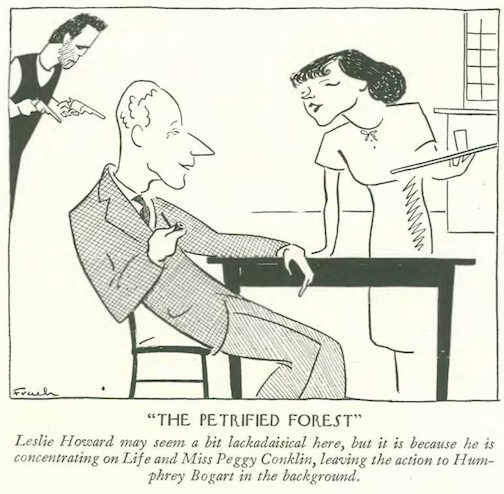

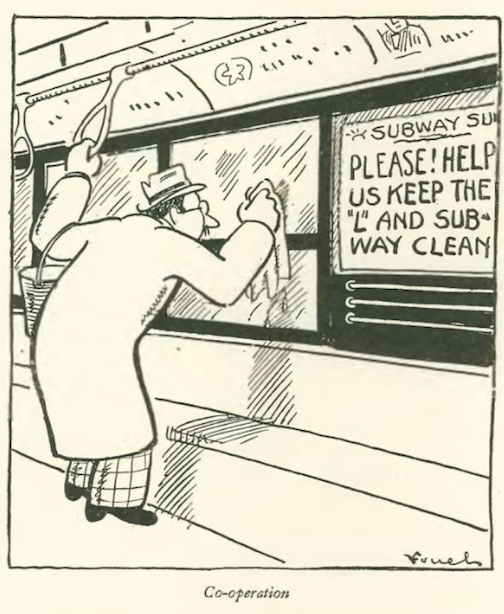

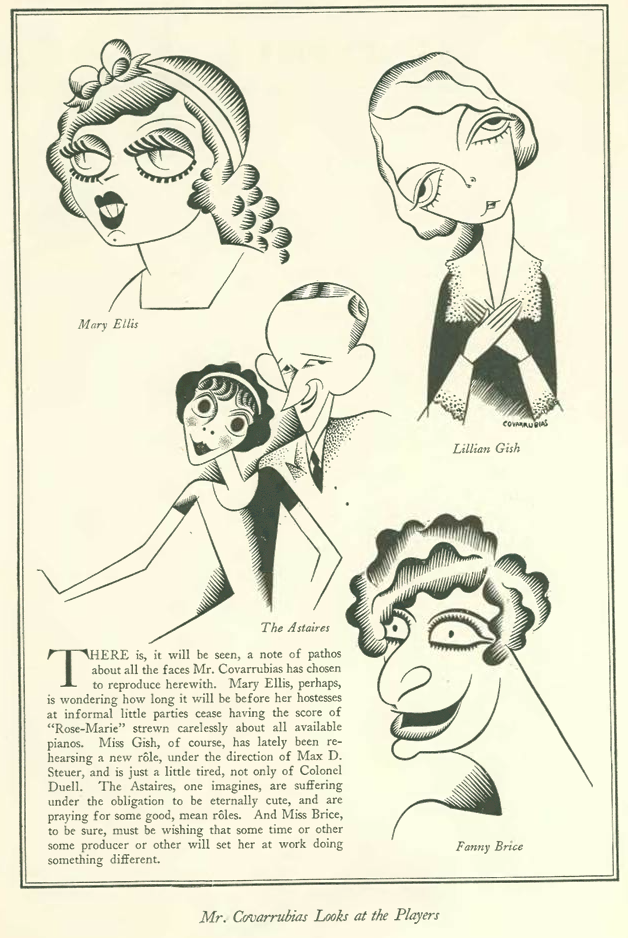

…on to our cartoonists, Al Frueh illustrated Humphrey Bogart as the coldblooded killer Duke Mantee in the 1935 play The Petrified Forest; the 1936 film adaptation would be Bogart’s breakout role in the movies…

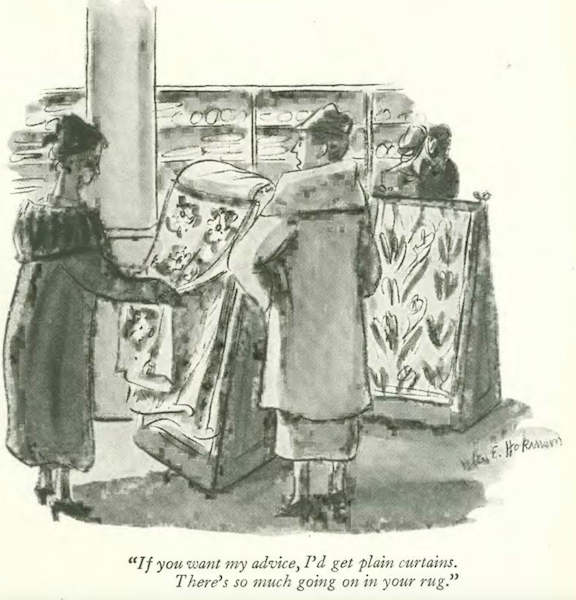

…Helen Hokinson went shopping for drapes…

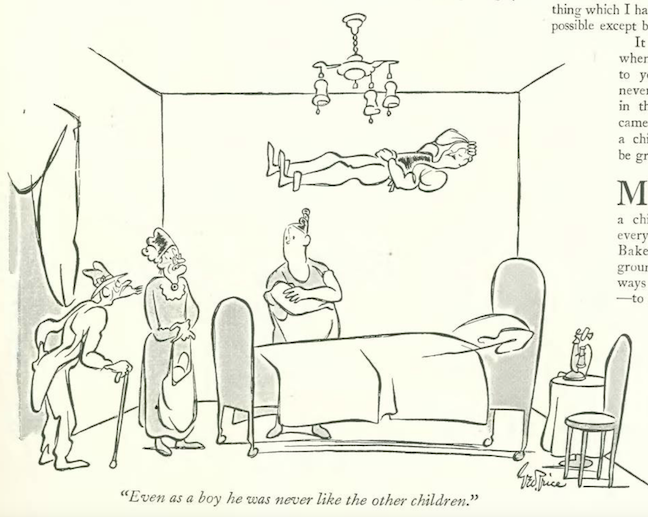

…George Price was all tied in knots…

…and still up in the air…

…Barbara Shermund dreamed of Venice…

…James Thurber gave us the life of the party…

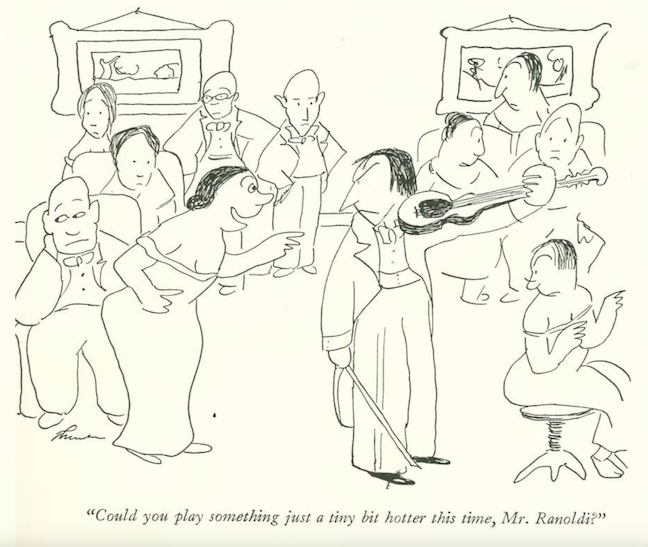

…and we close with Leonard Dove, and some unexpected party life…

Next Time: The Mouse Roars, In Color…