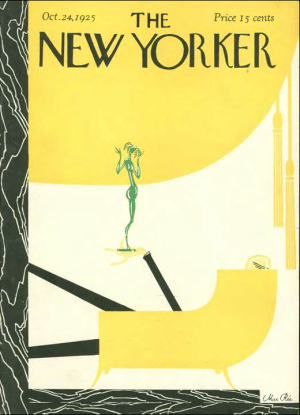

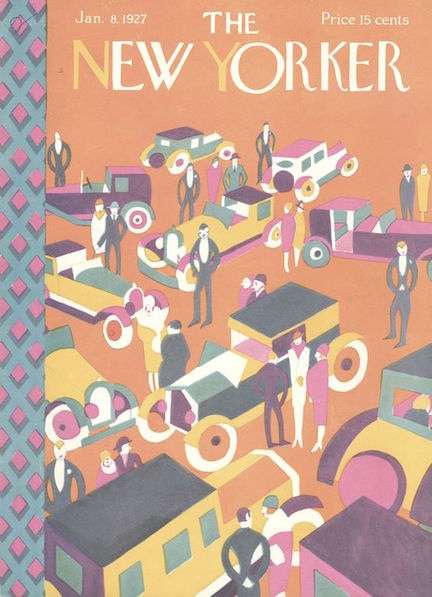

The January 8, 1927 issue of the New Yorker was all over the 27th Annual Motor Show at the Grand Central Palace, both in its lengthy review of the show and the many automobile ads throughout its pages.

Auto manufacturers discovered early on that cars didn’t need to advance technologically from year to year as long as there were superficial changes–trimmings and such–to dazzle the consumer:

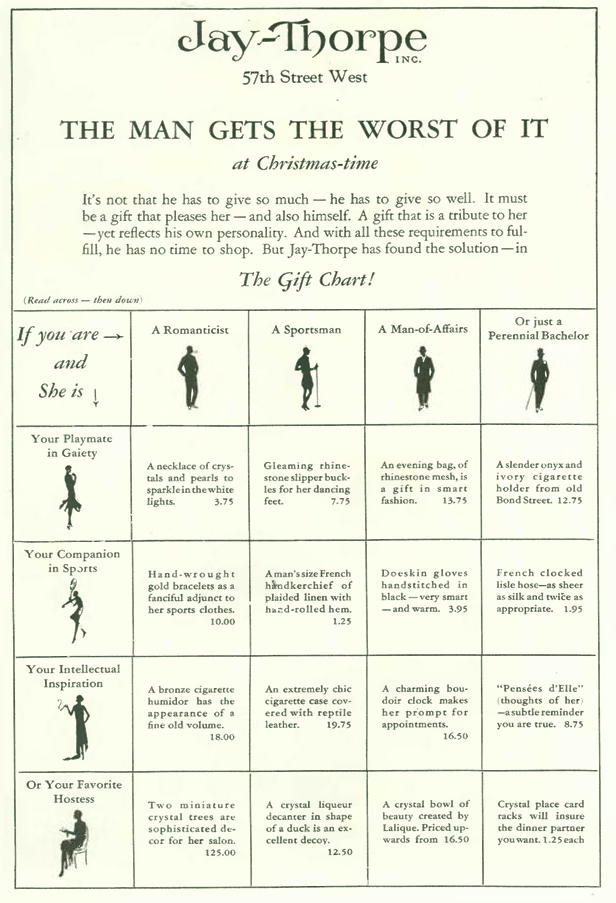

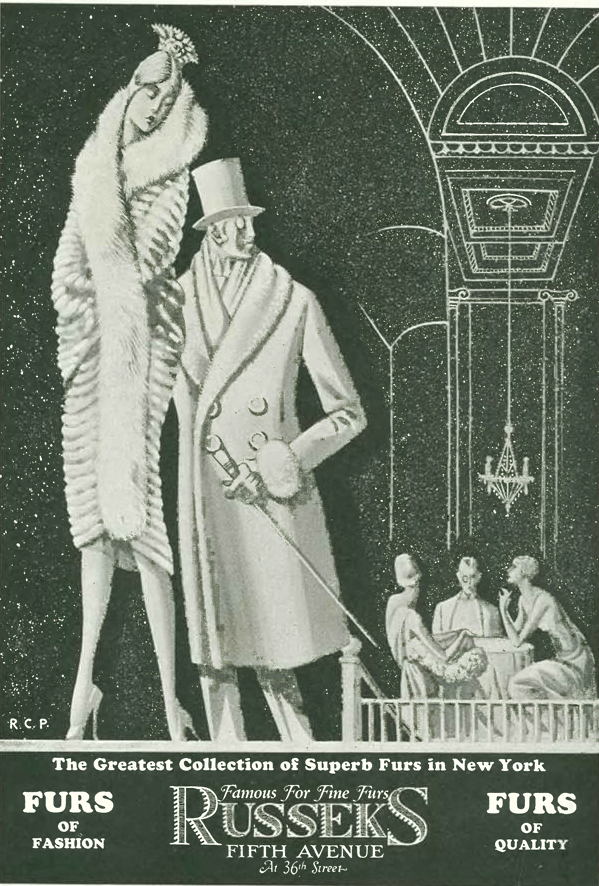

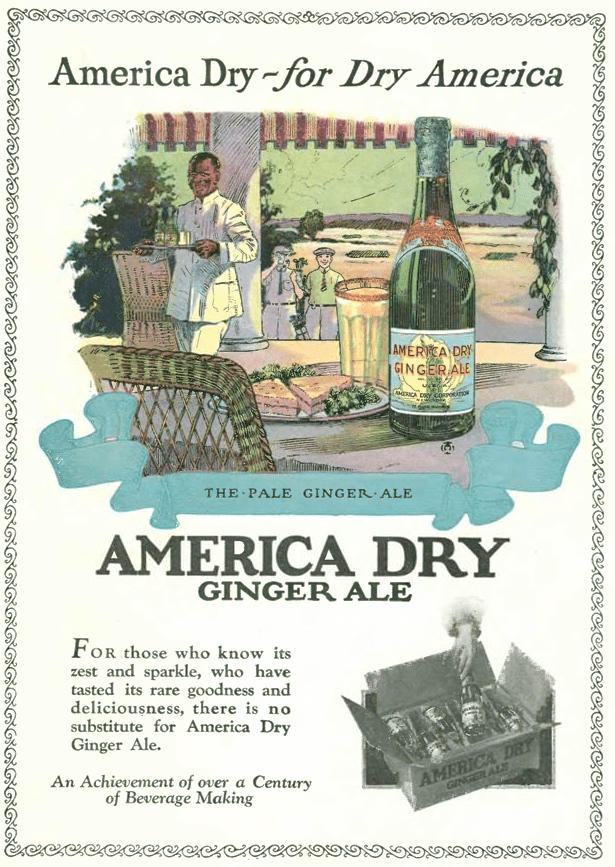

Advertisements in the New Yorker ranged from snobbish appeals to Francophiles…

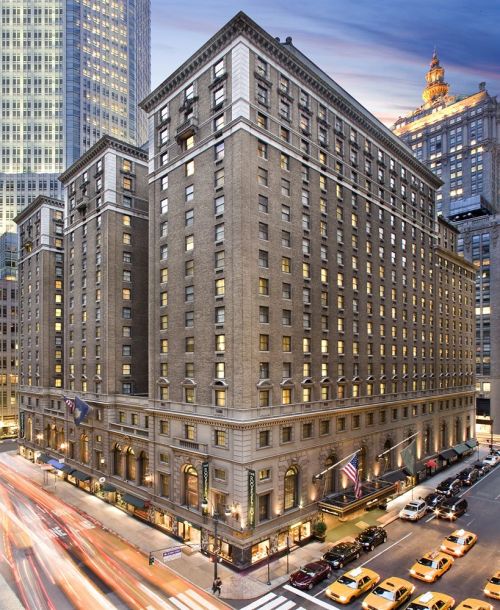

…to those who might be concerned about safety. Although cars weren’t very fast, they were fast enough to kill, and their plentiful numbers often overwhelmed a city with rudimentary traffic control.

…to those who might be concerned about safety. Although cars weren’t very fast, they were fast enough to kill, and their plentiful numbers often overwhelmed a city with rudimentary traffic control.

In his book, One Summer: America, 1927, Bill Bryson writes that New York in 1927 was the most congested city on earth. It contained more cars than the whole country of Germany, while at the same 50,000 horses (and wagons) still clogged the streets. More than a thousand people died in traffic accidents in the city in 1927, four times the number today.

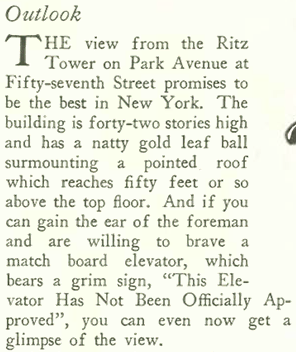

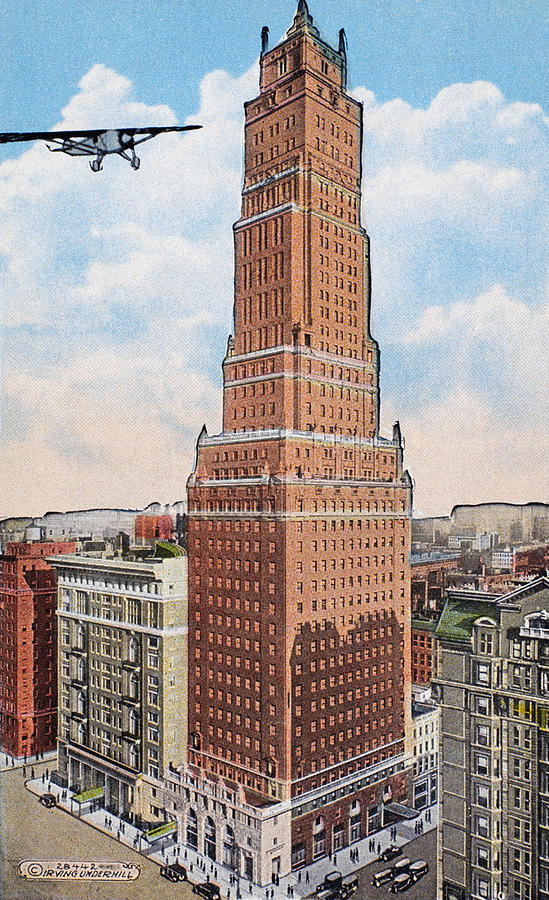

Traffic control was still in its infancy in the 1920s. Seven ornate bronze towers, 23 feet high, were placed at intersections along Fifth Avenue from 14th to 57th Streets starting in 1922. By 1927 smaller, simpler lights were mounted on street corners and the system of green, yellow and red was generally adopted.

Keeping with the motorcar theme, the issue also featured a profile (written by Lurton Blassingame) of Walter P. Chrysler, founder of the new car company that bore his name (Chrysler founded his company in June 1925 after acquiring and reorganizing the old Maxwell Motor Company). In just three years a famous New York City landmark bearing his name would pierce the skyline.

I recently noted that the fall 1926 editions of the New Yorker barely mentioned baseball, even though the Yankees made it to the World Series that year. No doubt the Black Sox scandal of 1919 still lingered in the minds of many fans. Morris Markey’s “Reporter at Large” column in the Jan. 8, 1927 issue suggested that the game, “no more important than the circus,” was still dishonest, thanks in part to its collusion with the newspapers:

Baseball might have been down and out, but actress Pola Negri still maintained her place in the spotlight with her latest film, Hotel Imperial.

Next Time: Bad Hootch…