The critic Gilbert W. Gabriel was more than a bit appalled by the spectacle at the old Olympic Theatre, where a tired and “degenerated” cast of burlesque performers took turns shaking their ancient haunches in the direction of the former Julliard student.

Gilbert’s article in the August 22, 1925 New Yorker, “They Call It Burlesque,” described the performance at the Olympic on East Fourteenth Street as “on its last legs.” The once “honest animalistic, gorgeously orgiastic burlesque show of ten or twenty years ago” had “degenerated in decency,” he wrote.

As the performers wiggled up and down the runways, Gilbert noted:

The audience was an equally sad lot:

There is some relief expressed when two comedians appeared, but they offer an unimaginative routine:

And then back to the dancers:

And still more…

Happier news over in “The Talk of the Town,” where jazz was getting some respect: “Jazz, successor to the outcast ragtime, each day is becoming acceptable. It is the young brother of the musical family, irresponsible and at time highly irritating, but, nevertheless, acknowledged.”

It was reported that even famed violinist Jascha Heifetz “dabbled” in jazz as an amusement, and writers of jazz were “no longer those products of East Side dives,” but rather included the likes of Buddy de Sylva, lyrist to Al Jolson, and George Gershwin, “high priest of jazz,” who was besieged by symphony conductors for his “Symphony in Blue” (better known today as Rhapsody In Blue).

“Talk” continued its lament of the changing face of Fifth Avenue:

And the Waldorf Astoria was being remodeled in order to add shops on the ground floor along with “125 bathrooms,” giving the famed hotel “a bath for almost every room.” In just four years the old Waldorf would be torn down and replaced by the Empire State Building.

“Talk” also noted the planting of Ginkgo trees in the city:

Although prized today for their beauty and hardiness, not all New Yorkers are in love with the strong odor of its fruit. In the June 30, 2008 issue of The New Yorker, Lauren Collins examined the activities of the “Anti-Ginkgo Tolerance Group” in her article “Smelly Trees.”

“Talk” also offered a brief glimpse into the latest adventures of Pola Negri, noting in its “This Week” section that the actress had paid “$57,000 customs dues in seized jewels…”

In other items, Helen Hokinson provided illustrations for an article on the horse races at Saratoga…

…John Tunis examined the life of tennis star Elizabeth “Bunny” Ryan in “Profiles” … and E.B. White and Alice Duer Miller offered their thoughts on why they liked New York:

“Moving Pictures” featured a lengthy review of Charlie Chaplin’s The Gold Rush. Theodore Shane (“T.S.”) wrote that the film’s opening night at the Strand attracted such celebrities as Will Rogers and Constance Bennett.

Shane observed that this “dramatic comedy” was a “serviceable picture,” but perhaps Chaplin was getting “too metaphysical about his pathos” and could have used some old-fashioned pie-in-the-face slapstick.

As an example, in a scene in a typical Klondike town, Shane wrote that “one might be given to expect wonders of Gold Rush burlesque with the old Chaplin at the receiving end of the Klondike equivalent of a custard. But one is doomed to disappointment, for Chaplin has seen fit to turn on his onion juices in a Pierrot’s endeavor to draw your tears…We cannot help but recall with a tinge of sadness, the old days when custard was young.”

Shane went on to give short but favorable reviews to Rex Reach’s Winds of Chance (at the Piccadilly Theatre), the film’s chief props consisting of “string ties, wooden saloons, ½ dozen cold-blooded murders and the tenderfoot who conquers everything…Shane also noted that the “spiritual features” of Tom Mix in The Lucky Horseshoe (at the Rialto) lent themselves delightfully to “a lovely and sensitive drama of moyen age and modern machinations in the Fairbanks style.”

In “Books,” Harry Este Dounce (“Touchstone”) suggested readers take a look at Carl Van Vechten’s Firecrackers as a good introduction to the writer’s unique style, while J.D. Bereford’s The Monkey Puzzle was deemed only “partly good” but worth reading.

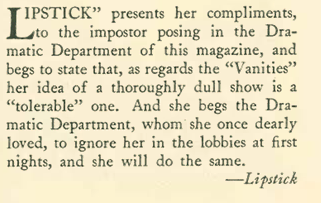

In her regular nightlife review (“When Nights Are Young”), Lois Long (“Lipstick”) playfully sparred with her New Yorker colleague, theater critic Herman J. Mankiewicz:

Long was referencing this Mankiewicz review in a previous issue (Aug. 8):

And it all started when Long offered this observation in her July 25 “When Nights Bold” column:

I hope you are fully sated. As a palate cleanser, I offer yet another droll observation of the world of old money by Gardner Rea:

Next time: The waning summer season…