Widely acknowledged as a classic, The 39 Steps further solidified British director Alfred Hitchcock’s image as a master of suspense with American film audiences.

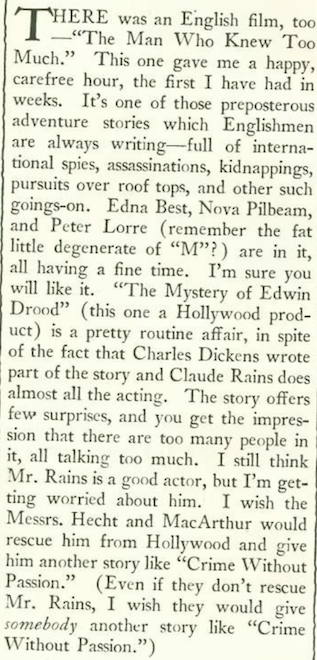

A successful follow up to 1934’s The Man Who Knew Too Much, Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps was conceived and cast by the Gaumont-British Picture Corporation as a vehicle to establish British films in America. The film also featured one of Hitchcock’s favorite plot devices—an innocent man forced to go on the run—seen in such notable films as 1942’s Saboteur and 1959’s North by Northwest. New Yorker film critic John Mosher was among the film’s many admirers:

* * *

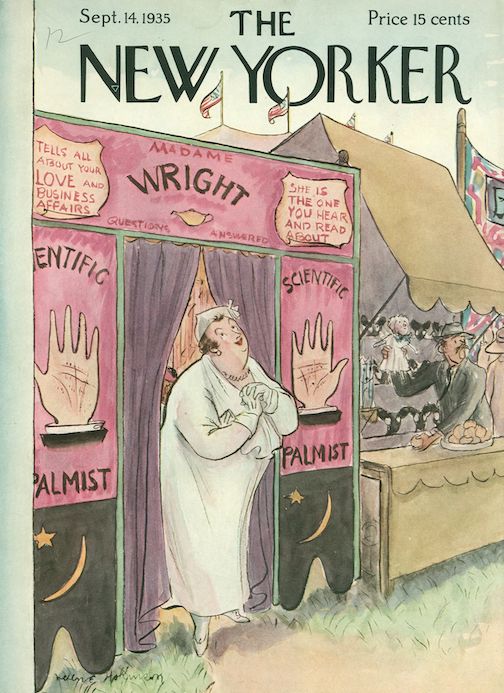

Pop-Up Stores

“The Talk of the Town” had a look at the “madhouse” on Nassau Street that daily erupted from noon to 2 p.m. as peddlers took over the street to hawk their wares.

* * *

Art of the Artless

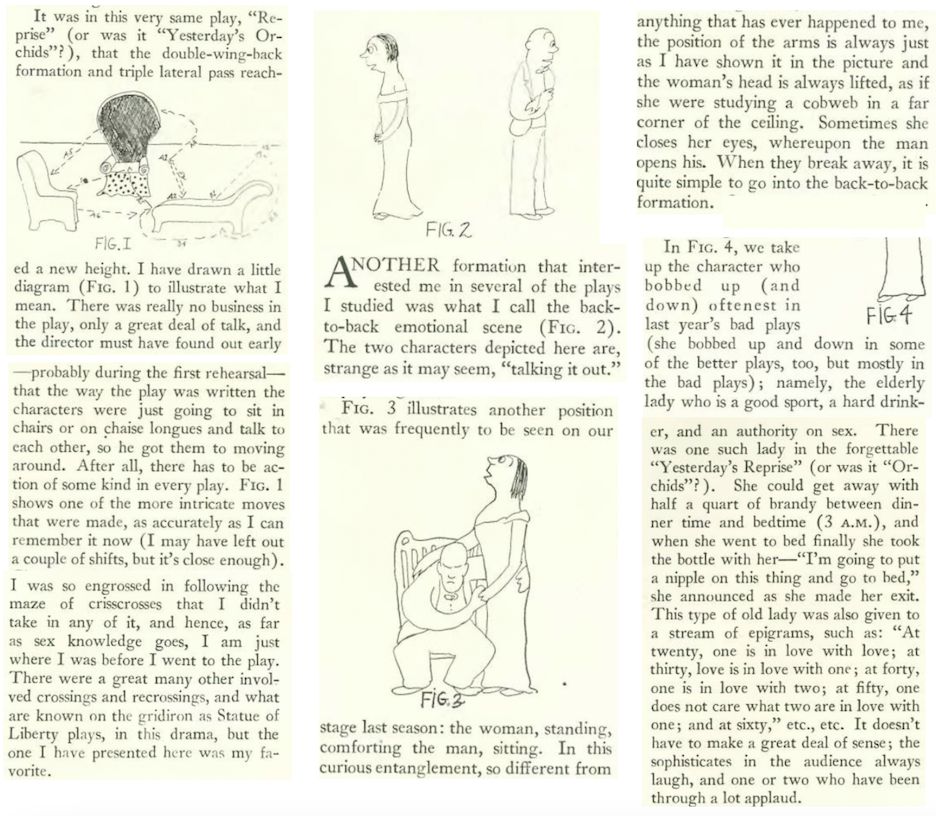

James Thurber dissected the workings of a “bad play,” examining varied techniques and familiar tropes. Excerpts:

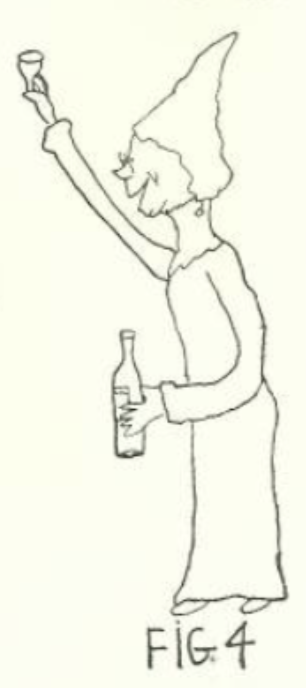

…below is the complete illustration for Fig. 4, which got cut off in the excerpt above…Thurber depicted “the elderly lady who is a good sport, a hard drinker, and an authority on sex.”

* * *

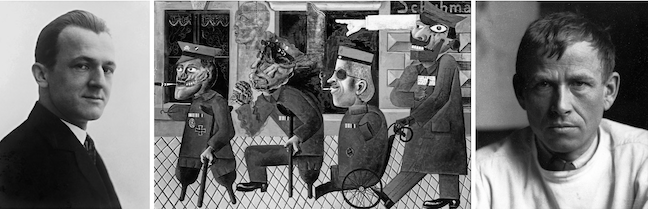

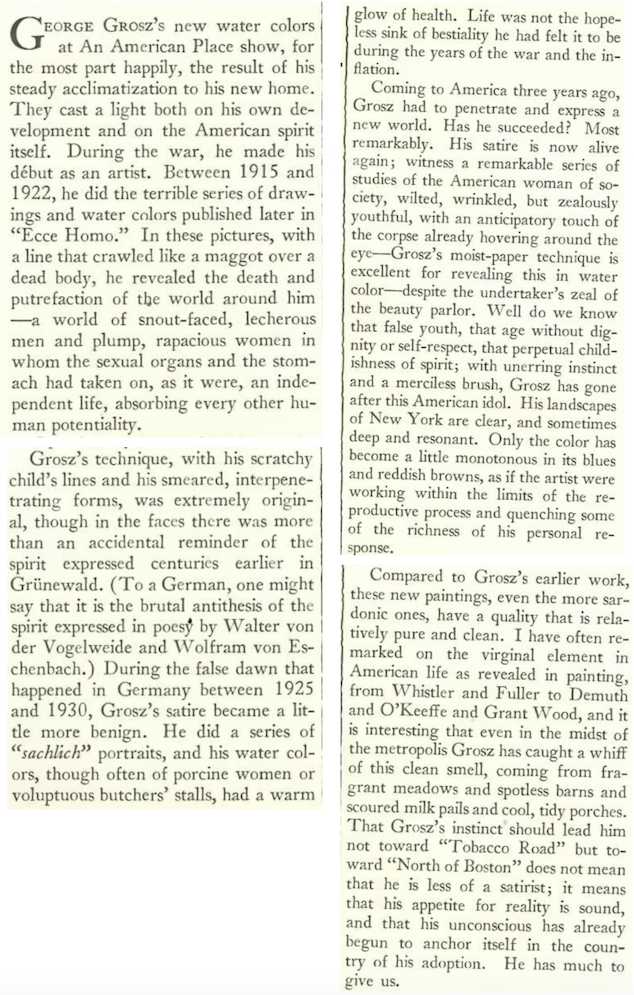

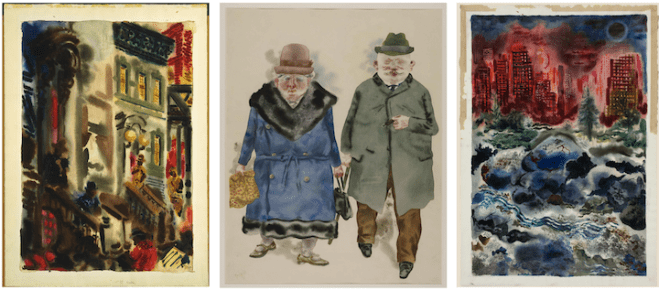

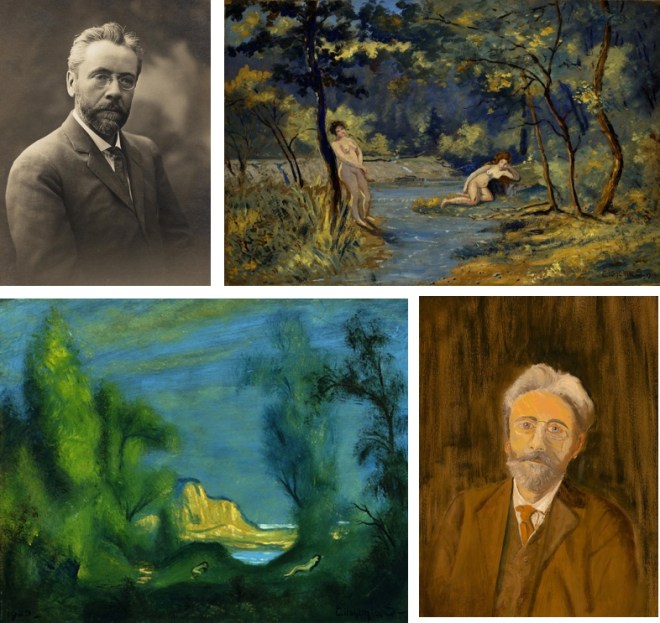

The Petulant Painter

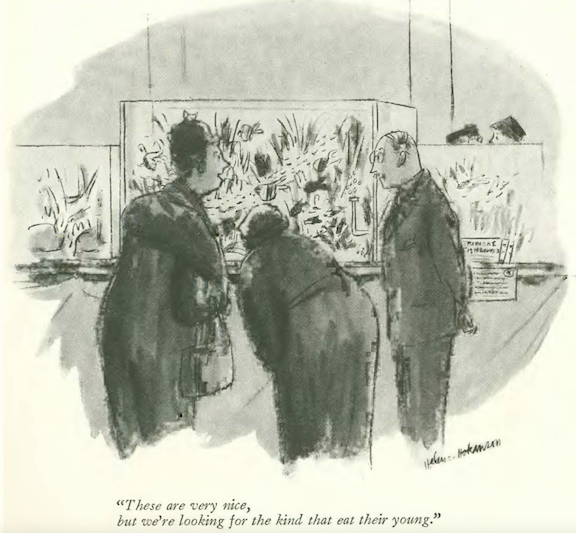

Known for a primitive style that included bizarre scenes of frolicking (or floating) voluptuous nudes, the painter Louis Michel Eilshemius (1864–1941) had a style all his own, and had no trouble telling anyone that his work was better than anything hanging in the finest museums (which would not consider him at all until after his death). In 1931 he began calling himself “Mahatma,” hence the title of this profile by Milton MacKaye (illustration by Hugo Gellert). Some brief excerpts:

Eilshemius regularly visited art galleries, loudly condemning the works on display. No wonder museums would not consider his odd paintings, which were probably best received by the French, including the artists Henri Matisse and Marcel Duchamp; the latter invited Eilshemius to exhibit with him in Paris in 1917.

Eilshemius’ mental stability had deteriorated substantially by the time MacKaye wrote the profile, which concluded with this sad, final accounting of the man’s life.

Eilshemius would die in the psychopathic ward of Bellevue Hospital in 1941. In the years since, his work has gained a wide audience and can be found in such collections as the Smithsonian, The Phillips Collection, MoMA and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

* * *

In Good Company

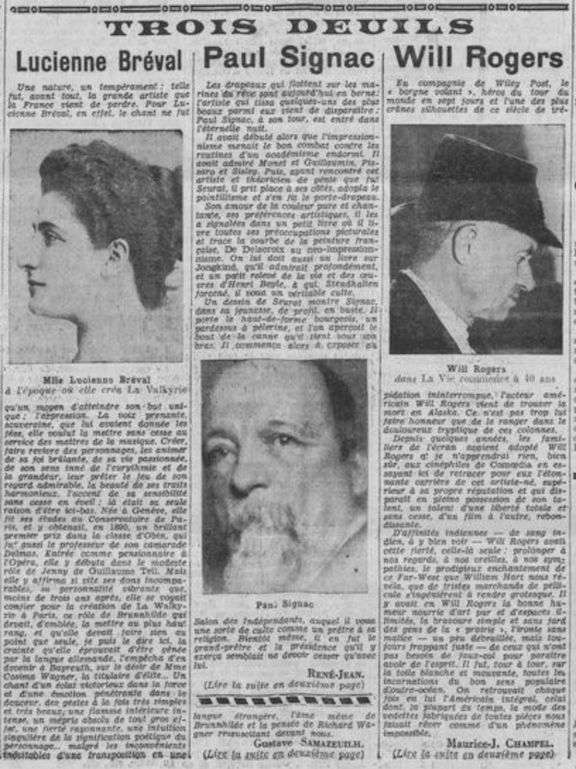

In her “Letter From Paris,” Janet Flanner noted that even the French honored the memory of Will Rogers, who had died in a plane crash with aviator Wiley Post on Aug. 15, 1935.

* * *

At the Movies

Coming down from The 39 Steps, John Mosher also sampled some of latest comedies gracing the silver screen…

…Mosher didn’t understand why Marion Davies, nearing the end of her film career, even bothered to appear in the romantic comedy Page Miss Glory (although she was also the producer), in which she portrayed a country girl who stumbles into fame while working as a chambermaid in a luxury hotel…

…Two For Tonight featured a lot of fine crooning from Bing Crosby, and some hijinks, but fizzled out in the end…

…of the three comedies, Mosher found The Gay Deception to be the most winning. Directed by William Wyler, the film featured a sweepstakes winner pretending to be a rich lady (Frances Dee) who encounters a prince masquerading as a bellboy (Francis Lederer)…hilarity ensued…

* * *

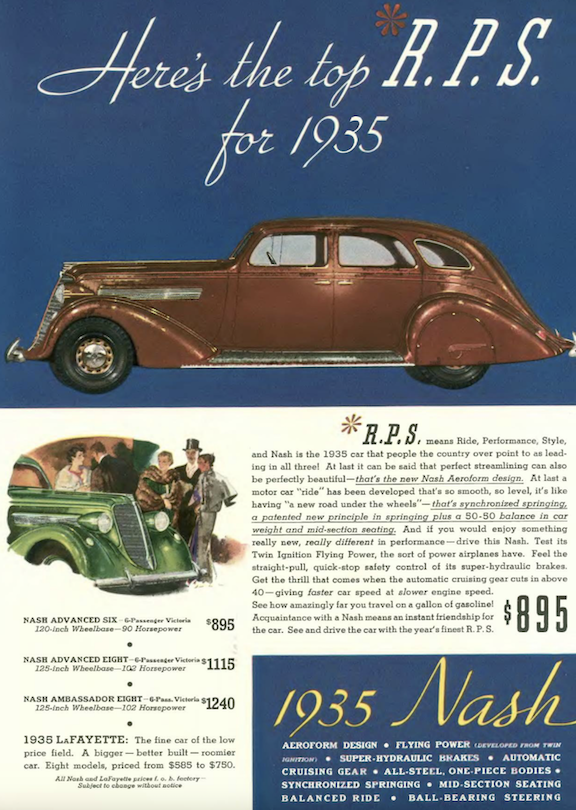

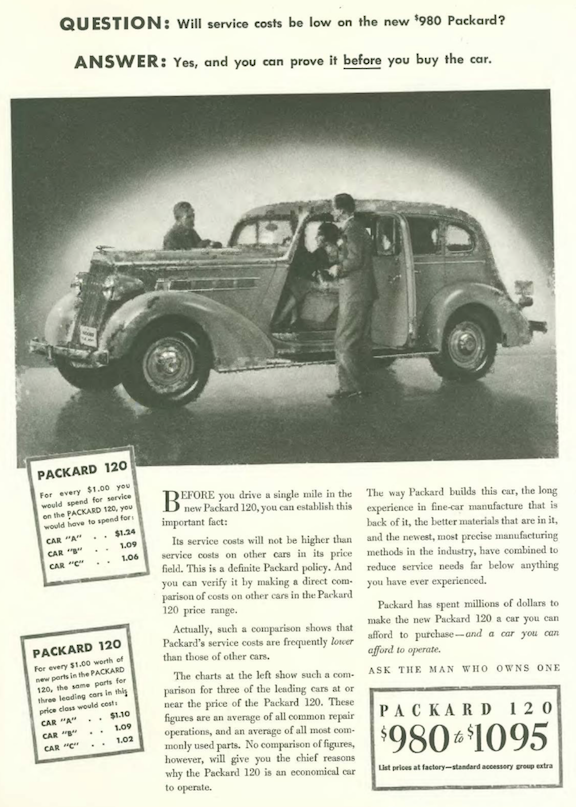

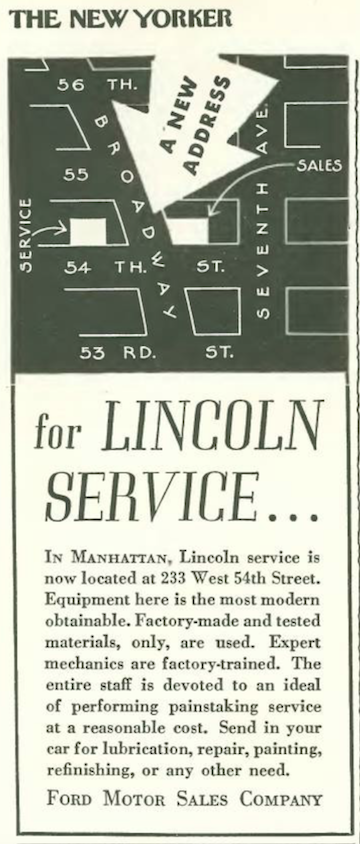

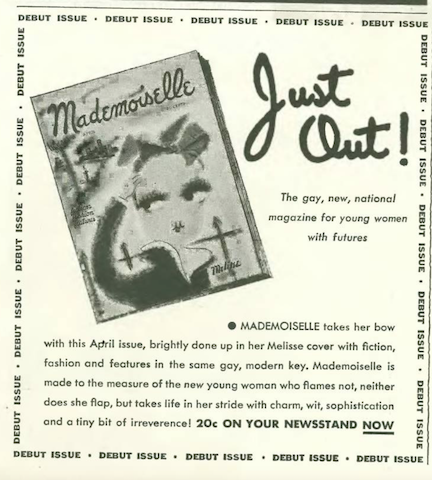

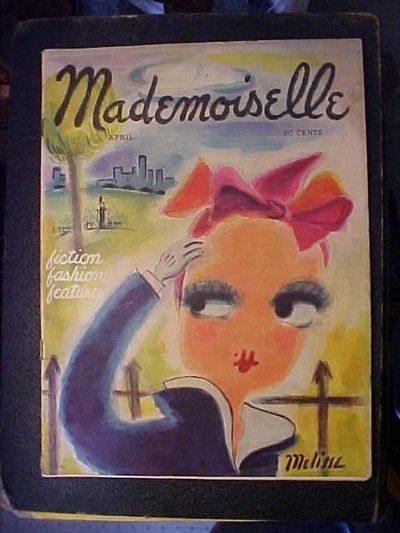

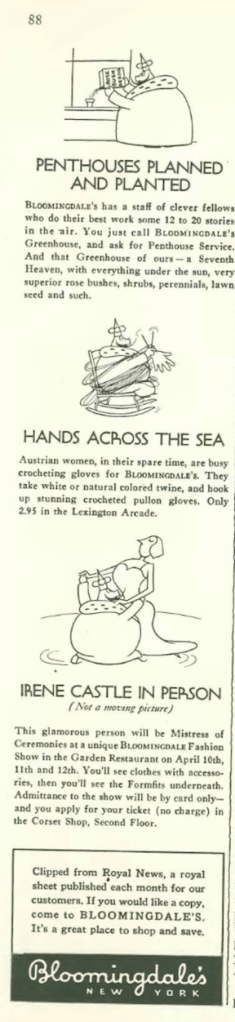

From Our Advertisers

We welcome fall with the latest fashion from Forstmann Woolens…

…and here is where those wool dresses were spun…

…the makers of leaded gasoline continued to promote their product in full-color spots…

…General Tire (like competitor Goodyear) played up the safety theme and potential perils to loved ones to tout their “blow-out proof” tires…

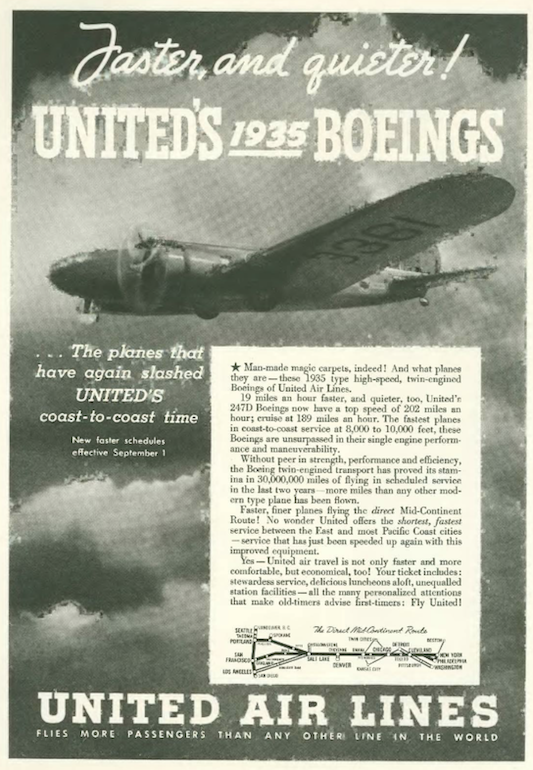

…like many advertisers in The New Yorker, United Air Lines appealed to the affluent, hoping some of them would take to the air, since only they could afford it…

…for reference…

…Abe Birnbaum, who contributed nearly 200 covers to the New Yorker, offered this rendition of Mickey Mouse to Stage magazine…

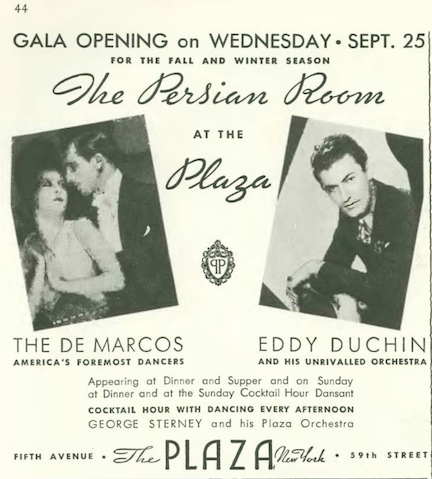

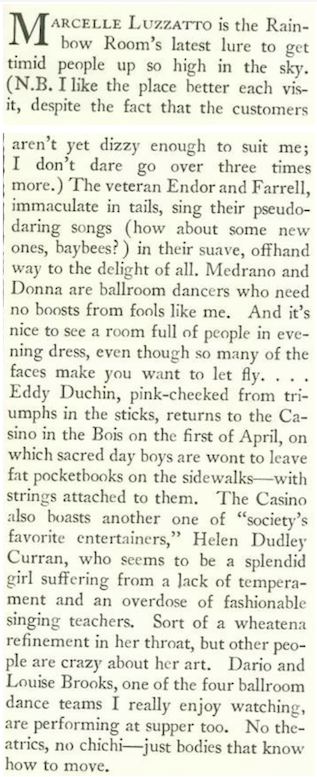

…heading to the back of the book we find the latest in entertainment at the Plaza…

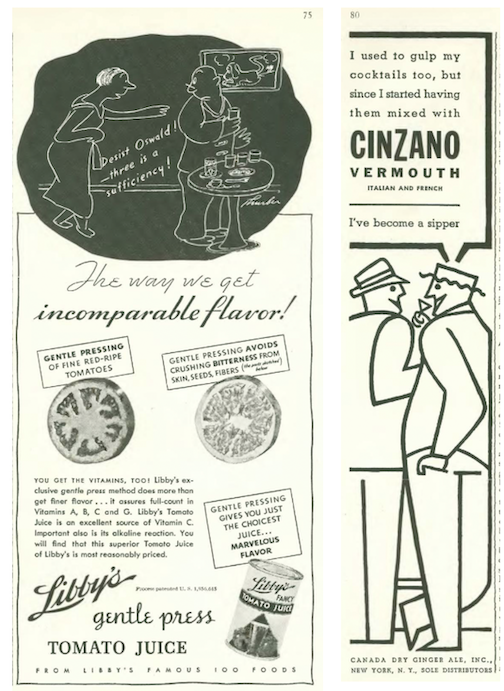

…James Thurber contributed the drawing at left (rendered in negative) on behalf of Libby’s tomato juice on page 75, and page 80 featured the spare, modern lines of a Cinzano ad…

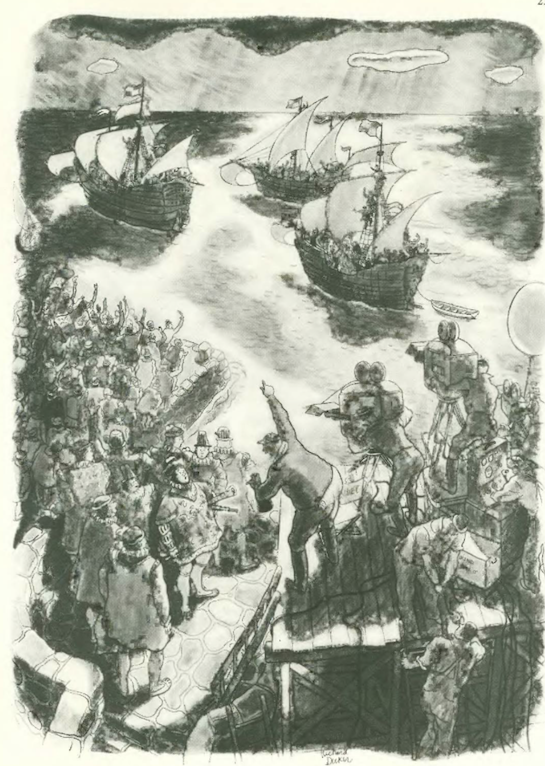

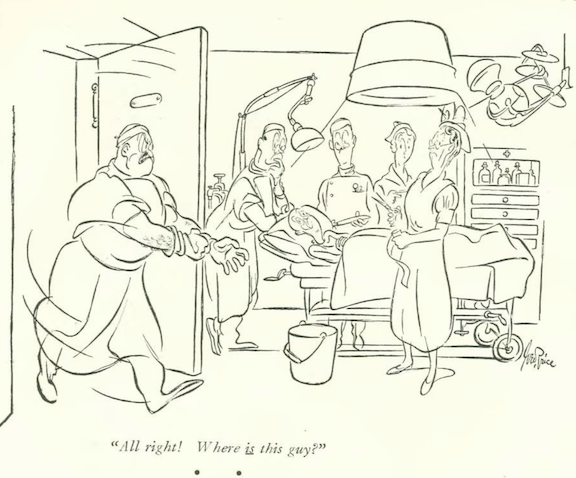

…our cartoonists include Richard Decker, on the set with a missing extra…

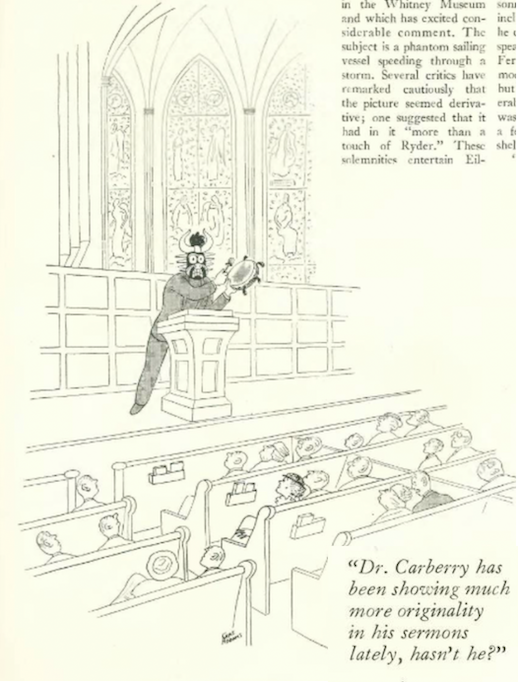

…Charles Addams offered a new twist on the Sunday sermon…

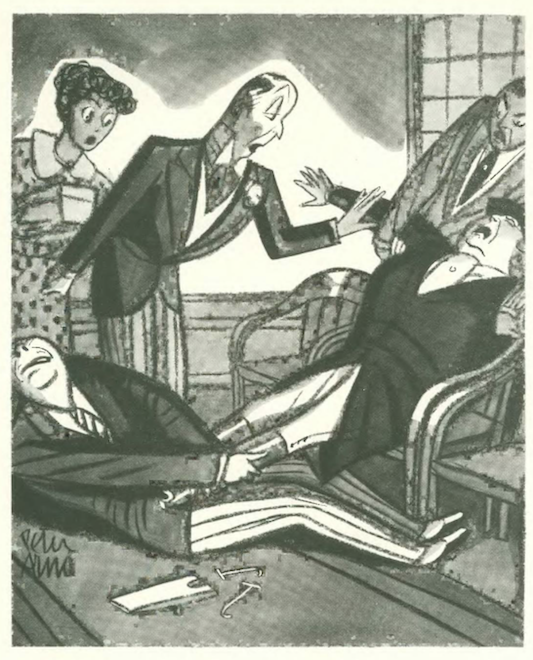

…Peter Arno found an epic struggle in the shoe department…

…Robert Day offered this energy-saving tip…

…and we close with Helen Hokinson, and a lively game of charades…

Next Time: All Dogs Go to Heaven…