The 1930s saw steady improvements in the fledging airline industry, which catered mostly to major businesses or well-heeled (and somewhat brave) folks who were interested in getting to places relatively quickly. Margaret Case Harriman reported on the many ways one could criss-cross the country by heading to the Newark Airport, the first major airport to serve the New York metro.

Writing for the “Out of Town” column, Harriman described how someone in 1934 could make their way to Los Angeles by boarding a 9 a.m. American Airlines flight in Newark and then changing over to a “sleeper plane” in Fort Worth around 10 p.m. that same day (top speed of the fastest plane was about 190 mph or 306 kph. The trip also required stops for refueling). The night flight from Fort Worth would deliver the traveler to Los Angeles the following day, at 7:55 a.m.—the trip totaled about 23 hours.

When we think of flying in the 1930s many of us recall the great travel posters featuring Pan American’s Clipper Ships—flying boats that took passengers to exotic locations in the Caribbean and in Central and South America. Harriman wrote:

Harriman closed with some advice to readers unfamiliar with flying, including putting drops of Argyrol (a silver-protein antiseptic) into ones eyes to “prevent that ticking sensation in the temples.”

* * *

No Offense Taken

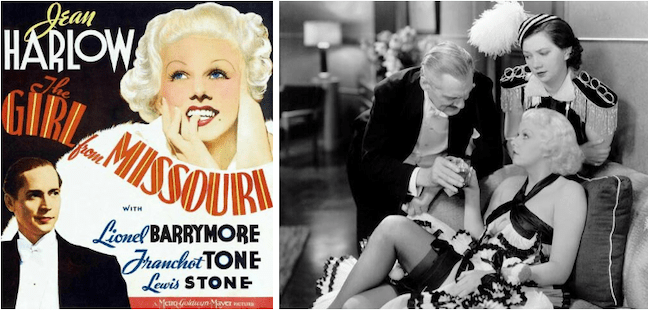

Critic John Mosher was no fan of Jean Harlow’s, but he did acknowledge her box office appeal, and that fans eagerly awaited the Blonde Bombshell’s next picture, The Girl from Missouri…with its “usual plot of a gold-digger and millionaries.” Mosher also noted that Harlow, along with Mae West, was a prime target of reformers (see Hays Code) who wanted to ban “immorality” from the pictures, and he was eager to see how the Puritans had wielded their new censoring shears on the film.

* * *

From Our Advertisers

We begin with another ad from the makers of Spud menthol cigarettes, who deployed what seemed like every known visual metaphor to suggest that smoking their cigarettes “all day” would leave one feeling cool, clean and fresh, in this case as a blanket of newly fallen snow (an appealing sight in that hot summer of 1934)…

…R.J. Reynolds deployed any number of tricks to sell their Camels, from ads promoting their health benefits to endorsements by wealthy socialites, in this case Sarah Lippincott (“Mrs. Nicholas Biddle”) of Philadelphia…

…snob appeal was not limited to cigarette ads, as this full page from the folks at Chevrolet attests…

…zooming in on the copy that accompanied the above ad, we find that this fictive Chevy owner was a “marked woman” sought out by paparazzi and admired by couturiers…

…Dr. Seuss continued his series of weird ads for Flit insecticide…

…Helen Hokinson illustrated this patrician picnic scene to promote Heinz’s line of sandwich spreads…

…and we kick off our cartoons with Helen again, observing a proud moment…

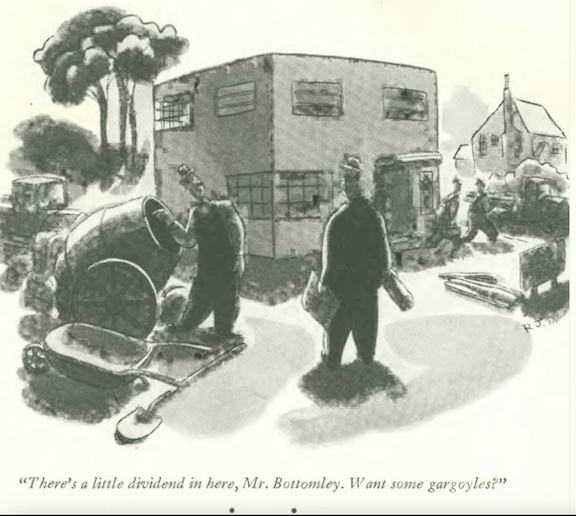

…Robert Day offered this observation on modern architecture…

…Rea Irvin skewered the puritan set with his latest bird illustration…

…William Steig’s precocious “Small Fry” visited Coney Island…

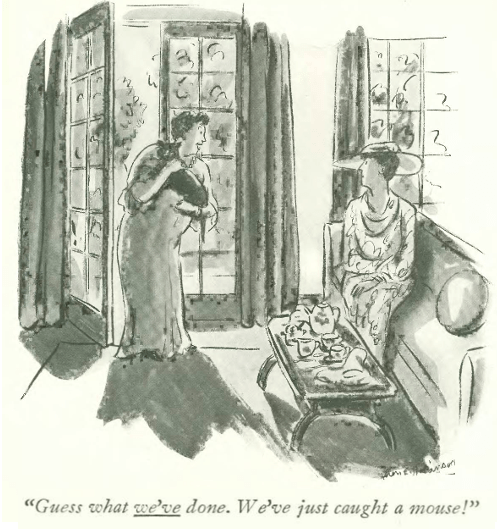

…and we close with E. Simms Campbell, and a sly introduction…

Next Time: Dizzy Drinks…