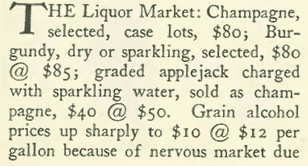

The woes of Prohibition were acutely felt by the readership of The New Yorker. The magazine responded in kind with its continued criticism of the law’s enforcement and particularly the tactics of Manhattan District Attorney Emory C. Buckner, whose agents continued to padlock restaurants and clubs suspected of selling alcohol.

The New Yorker previously called the padlocking tactic a “promotional stunt” that would ultimately backfire (I wrote about this in a previous blog post last March).

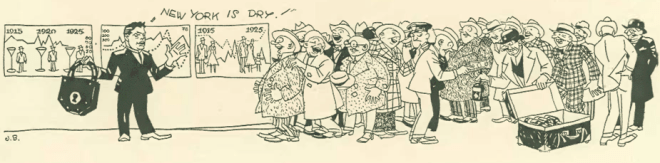

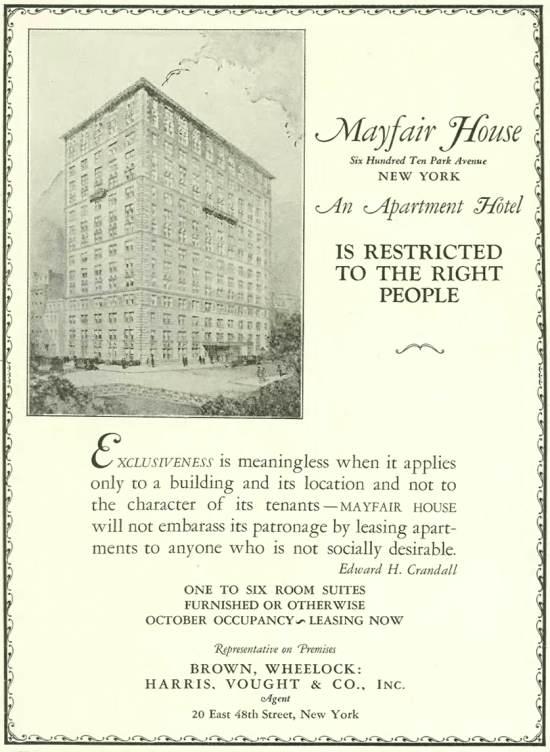

Both the “The Talk of the Town” and “Tables for Two” took aim at Buckner this time around. “Talk” led with this item, accompanied by the art of Johan Bull:

“Talk” also made a call to action by “men of virtue:”

Heck with statements. Lois Long just wanted to have some fun, and led her column, “Tables for Two,” with her own attack on Buckner and on the “stupidity” of establishments that were closed by Buckner’s agents (I include art that accompanied the column by Frank McIntosh—at least that is what I think the “FM” stands for; if I am in error, someone please correct me!):

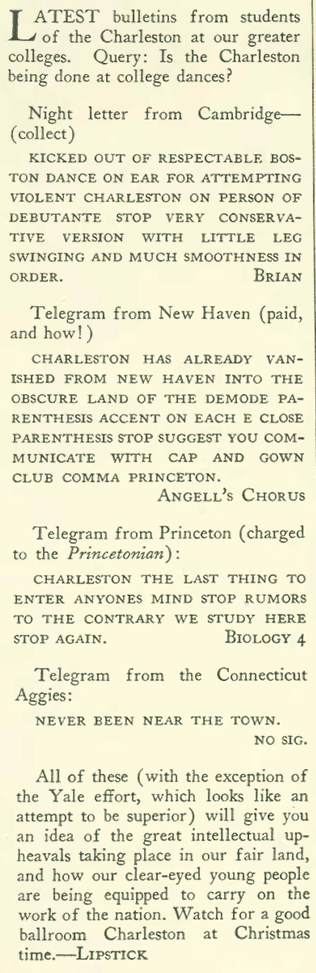

In a previous column (Oct. 17), Long pondered the popularity of a new dance, the “Charleston.” She closed her Oct. 31 column with “telegrams” from exemplary colleges in answer to the query: “Is the Charleston being done at college dances?”

W.J. Henderson wrote a lengthy article about the upcoming opera season at the Metropolitan Opera (it was opening with La Gioconda), and recalled the days after World War I when the once-popular German singers suddenly grew scarce on the American stage.

According to Henderson, this led to a general falling off of quality in the performances, a situation made even worse by the absence of the late, great Enrico Caruso on the Metropolitan’s stage.

In other items, John Tunis wrote about Illinois All-American halfback Red Grange in “Profiles,” calling him “a presentable youth of twenty-two…well-groomed, he would pass anywhere—even in the movies—for a clean type of American manhood.”

Tunis also noted that Grange had been offered a “half a million” to star in movies, and that professional football was ready to offer him a sum “that would cause even the once-mighty Ruth to blanch.” Grange, known as “The Galloping Ghost,” would later join the Chicago Bears and help to legitimize the National Football League (NFL).

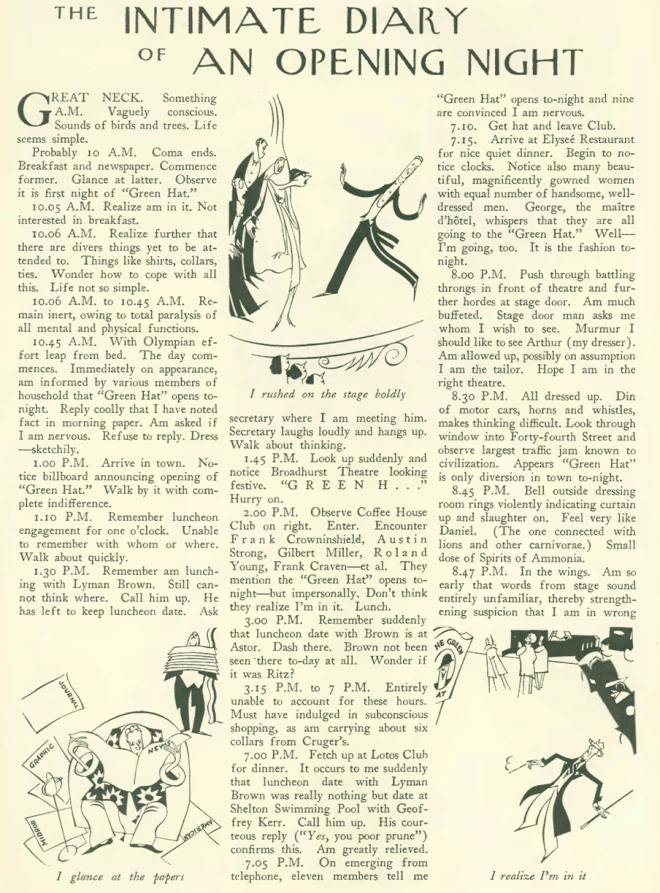

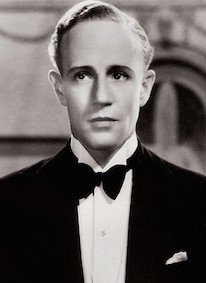

The young actor Leslie Howard, who was appearing on Broadway in Michael Arlen’s The Green Hat, wrote a humorous account of theatre life in “The Intimate Diary of An Opening Night.”

It was one of seven articles on the acting life that Howard (perhaps best known for his role as Ashley Wilkes in Gone With the Wind) would write for The New Yorker between 1925 and 1927.

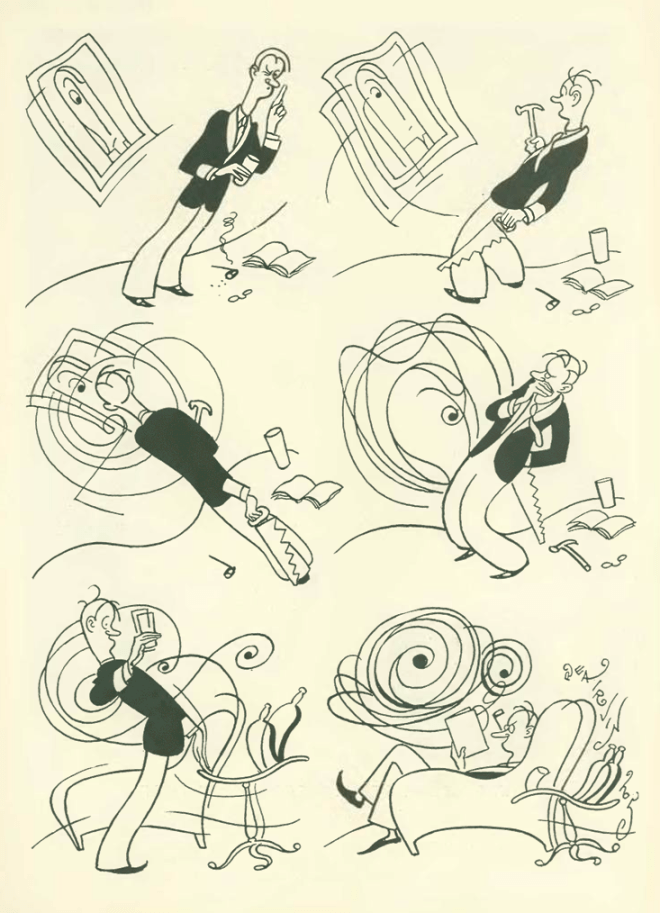

For the record, I include Howard’s first New Yorker article here (with Carl Rose cartoon):

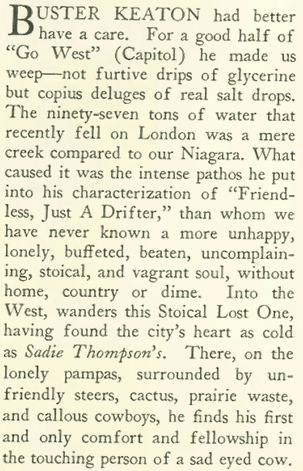

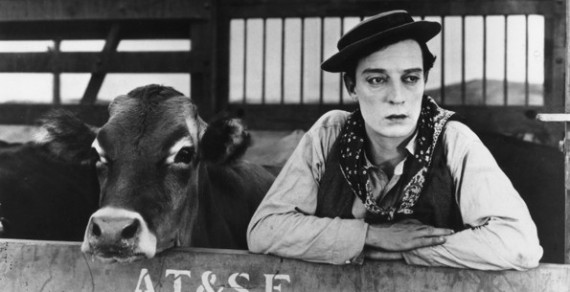

“Motion Pictures” looked at Buster Keaton’s new film, Go West…

Theodore Shane wrote that what at first seemed to be a real weeper…

…turned into a comic romp thanks to the introduction of the “sad-eyed cow…”

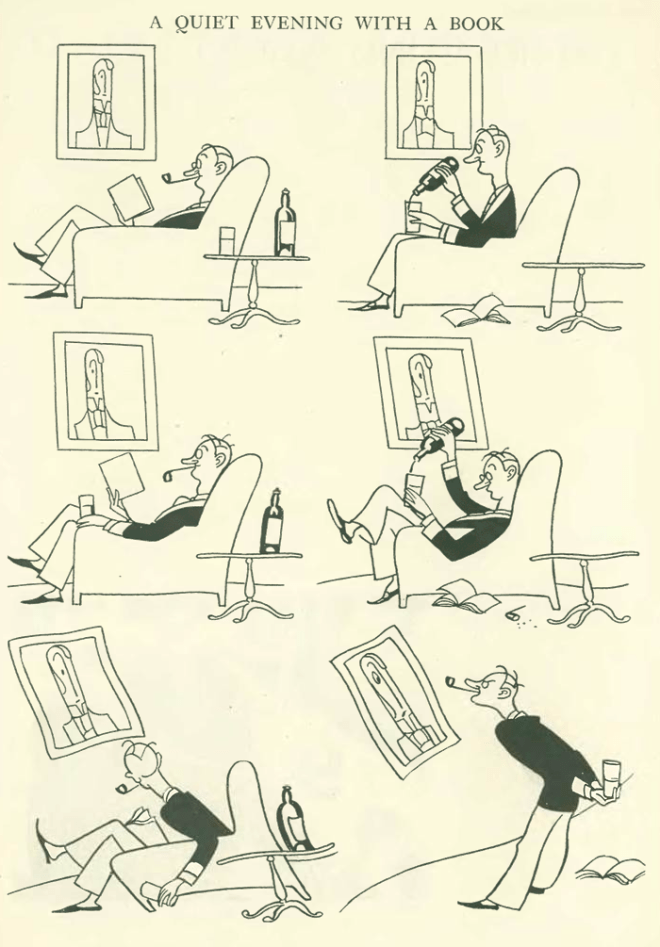

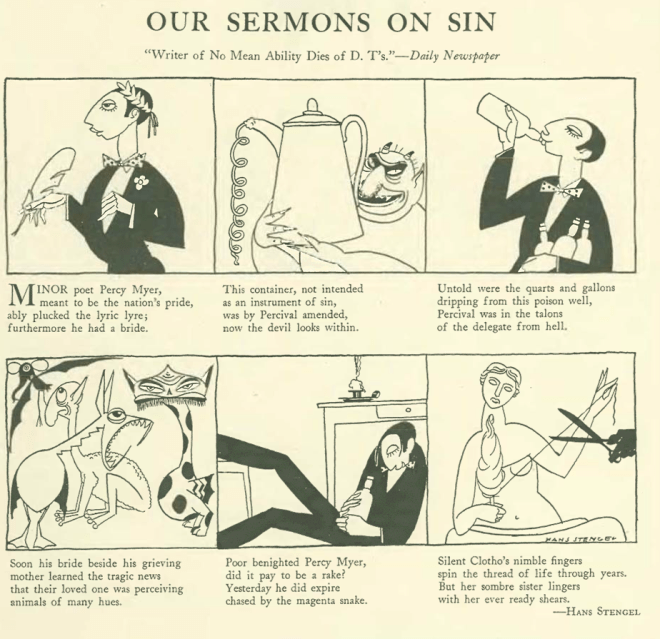

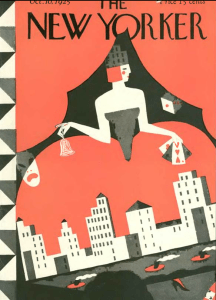

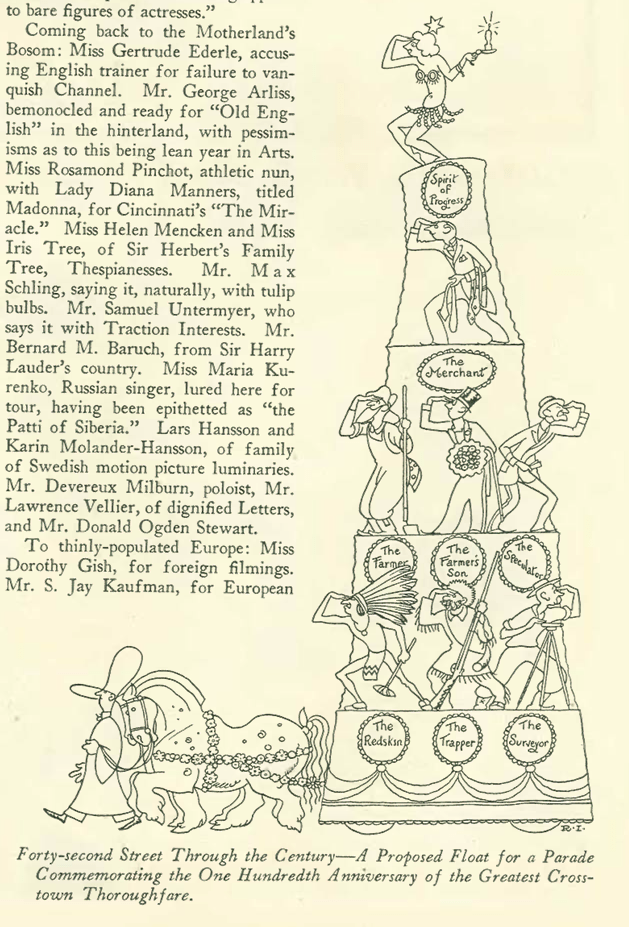

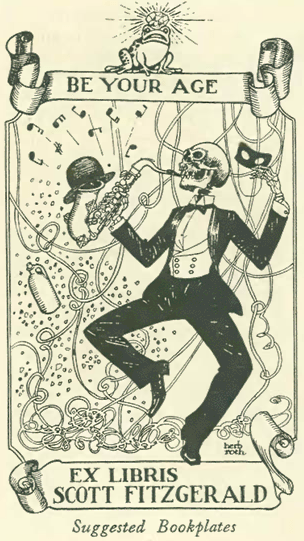

And finally, in keeping with the Prohibition theme, here is a center-spread cartoon by Rea Irvin that seemed to depict the results of consuming too much bootleg booze:

Next Time: Oh Behave…