Above: Bill "Bojangles" Robinson demonstrating his famous stair dance, which involved a different rhythm and pitch for each step. At left, Robinson in Broadway's Blackbirds of 1928; at right, publicity photo circa 1920s. (Vandamm collection, New York Public Library/bet.com)

Bill “Bojangles” Robinson (1878–1949) is considered one of the greatest tap dancers of all time, introducing a style of remarkable lightness and complexity that was perhaps best represented by his famous stair dance.

St. Clair McElway wrote about the 57-year-old Robinson in a two-part profile that examined his personal life and habits, including his propensity for getting shot. Two brief excerpts:

The New Yorker profile coincided with Robinson’s rising career in films, including four he made with Shirley Temple. For the 1935 film The Little Colonel, Robinson taught the stair dance to the child star, modifying his routine to mimic her movements. Robinson and Temple became the first interracial dance partners in Hollywood history (however, the step dance scene was cut from the film shown to Southern audiences). Temple and Robinson, who became lifelong friends, also appeared together in 1935’s The Littlest Rebel, 1938’s Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm and 1938’s Just Around the Corner.

Robinson is remembered for his generous support of fellow dancers including Fred Astaire, Eleanor Powell, Lena Horne, Sammy Davis Jr and Ann Miller, as well as his support for the career of 1936 Olympics star Jesse Owens.

Although Robinson was the highest paid black performer of his time, his generosity with friends as well as his gambling habits left him penniless at his death from heart failure in 1949. Longtime friend Ed Sullivan paid for Robinson’s funeral, and more than 30,000 filed past his casket to pay their respects.

* * *

In a Romantic Mood

That is how St. Clair McKelway found Hollywood in two of its latest offerings, The Barretts of Wimple Street and Caravan. To his relief, he found the Hollywood version of Barretts quite “sensible”…

…as for Caravan, McKelway wrote that he’d “never seen a picture with so much grinning in it.” He found the “peculiar, unreal gleam” of the actors’ teeth a real distraction in closeup shots.

* * *

From Our Advertisers

The Oct. 6 issue opened with a study in contrasts: an image of two Civil War veterans swapping stories over whiskey on the inside front cover, paired with an illustration of a lithe model sheathed in the latest fashion from Bergdorf…

…the folks at Campbell’s continued to suggest that their canned soup was a delight of the elite…

…Heinz took a similar tack, showing the smart set having fun with their sandwich spreads…

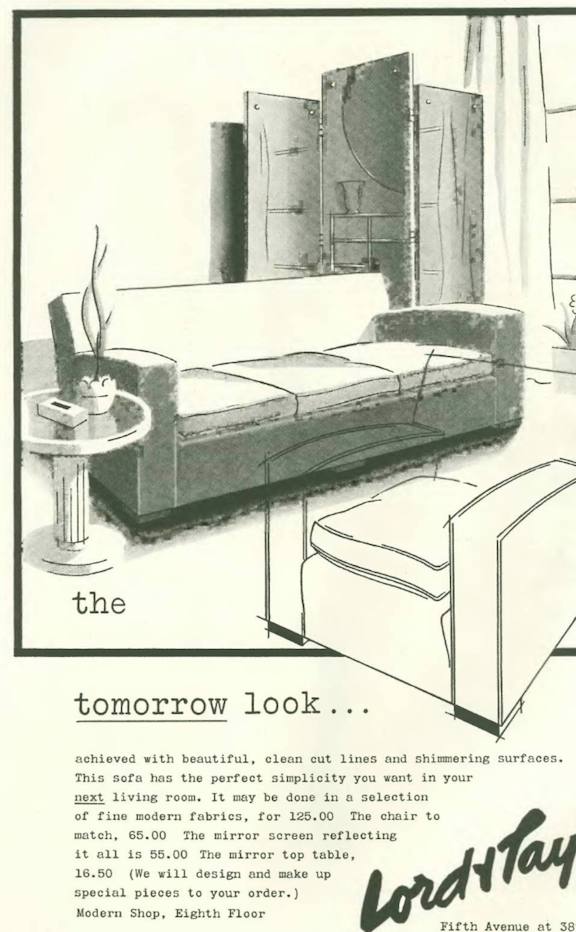

…Lord & Taylor touted its “tomorrow look” in furniture…

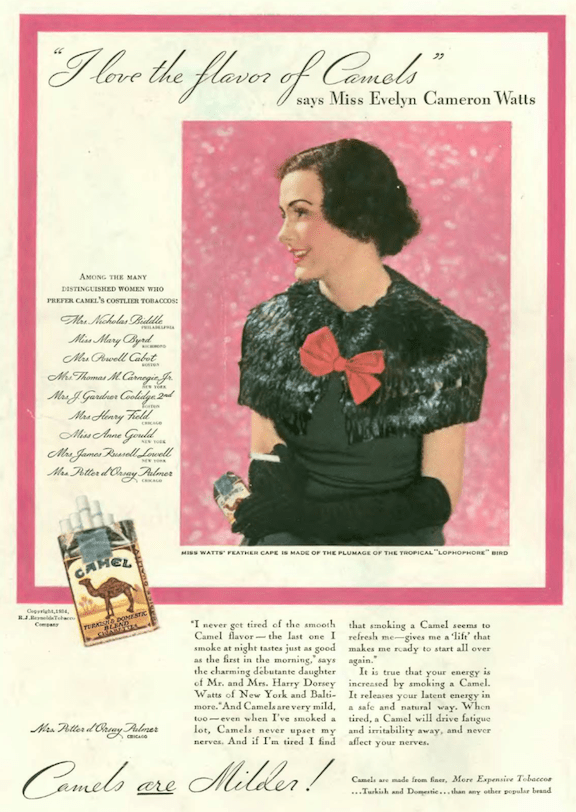

…R.J. Reynolds continued its series of “distinguished women who preferred Camel’s “costlier tobaccos,” adding to their growing list a the “charming debutante” Evelyn Cameron Watts, who later became Evelyn Watts Fiske (1915–1976)…

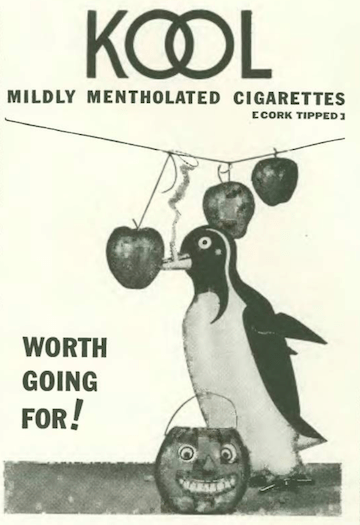

…in contrast to Camel’s fashionable ads, the upstart menthol brand Kool offered a series of cheap, back-page ads featuring a smoking penguin, here in the Halloween spirit (detail)…

…another recurring back page ad was this weird spot from Satinmesh, a product that apparently helped close a woman’s “gaping pores”…those pores apparently prompted one man to ponder the eternal why…

…on to our cartoonists, we begin with a two-page spot by Carl Rose…

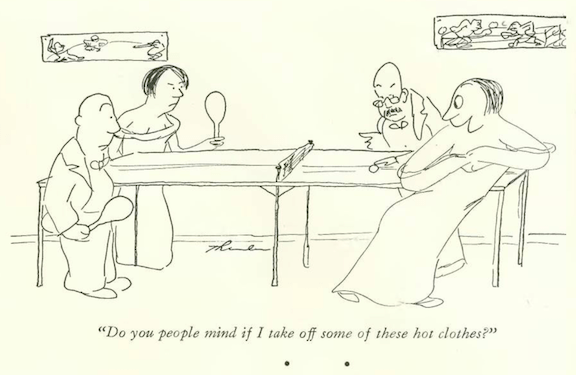

…James Thurber spiced up a game of ping-pong…

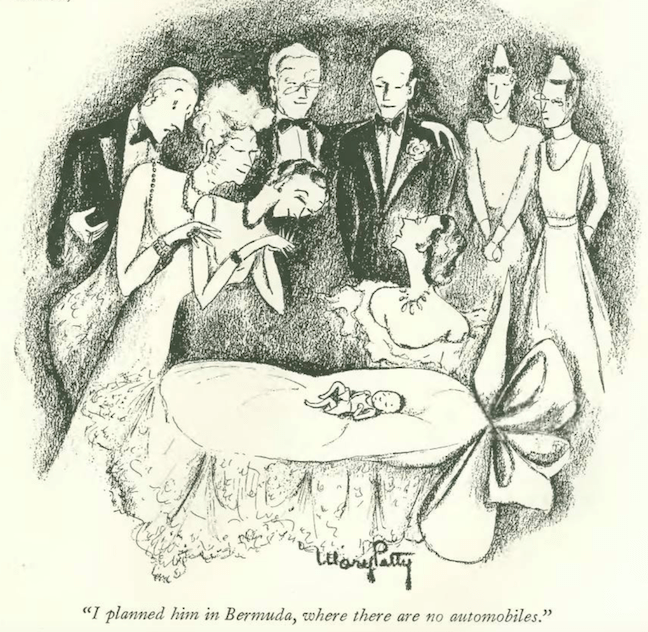

…Mary Petty explored the miracle of birth…

…Peter Arno discovered you’re never too old to play with toys…

…Garrett Price offered a young man’s perspective on a father’s avocation…

…Alain (Daniel Brustlein) gave us a disappointed plutocrat on vacation in Mexico…

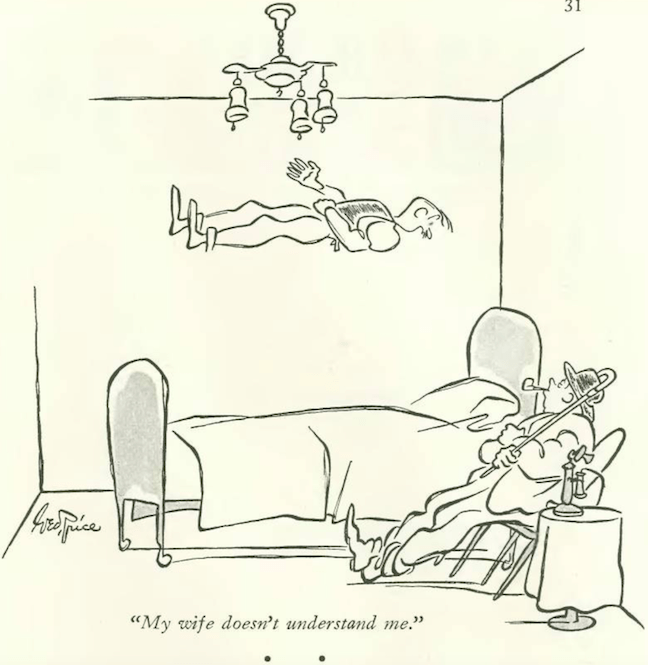

…George Price continued to mine the humor of his “floating man” series…

…and contributed a second cartoon that featured some office hijinks…

…and Otto Soglow returned without The Little King, offering in its stead the closest thing to royalty in America…

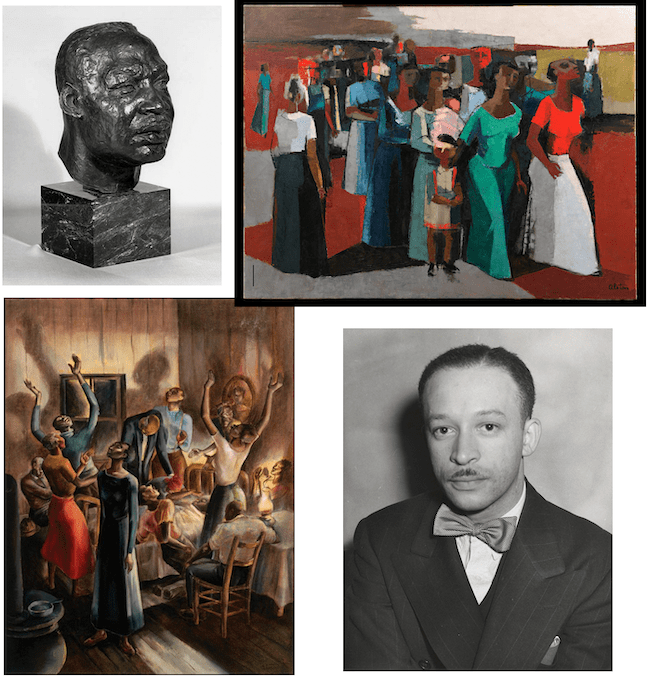

Before we sign off, a note on the Oct. 6 cover artist, Charles Henry Alston (1907–1977). A Harlem-based painter, sculptor, illustrator, muralist and teacher, Alston was active in the Harlem Renaissance and was the first Black supervisor for the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project. In 1990, Alston’s bust of Martin Luther King Jr. became the first image of an African American displayed at the White House.

For more on Charles Alston, read “The Painter Who Wouldn’t Be Pigeonholed” in Columbia College Today.

Next Time: The Age of Giants…