In my previous post, I hinted that “social errors” would be the topic of this entry, and in a sense that title describes the stance New Yorker editors were taking toward the continued demolition and remodeling of old city landmarks.

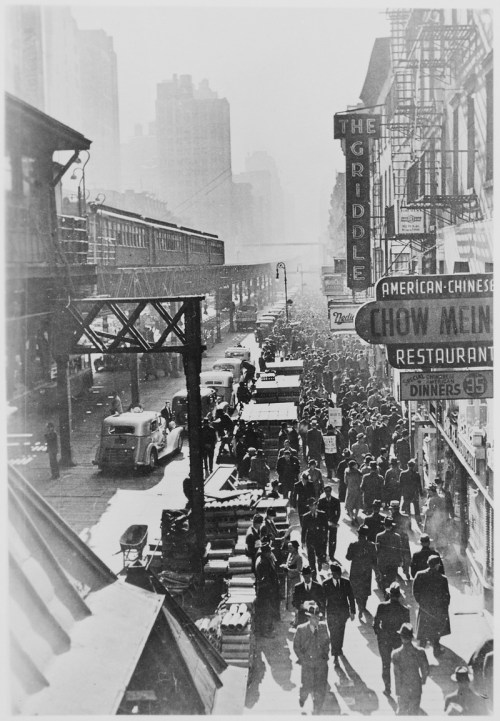

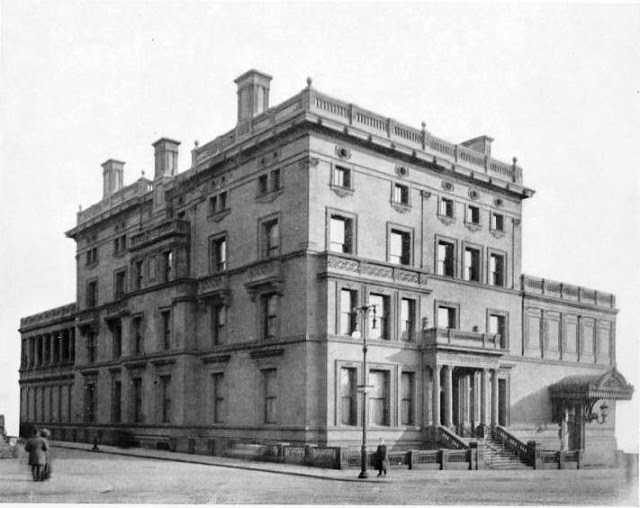

“The Talk of the Town” reported that two more Fifth Avenue mansions on “Millionaries Row” were soon to be demolished: the Brokaw and Yerkes mansions (the photo at the top of this entry depicts workmen taking a sledgehammer to a chimney atop the Brokaw house–not in 1925, but in 1965–more on that later).

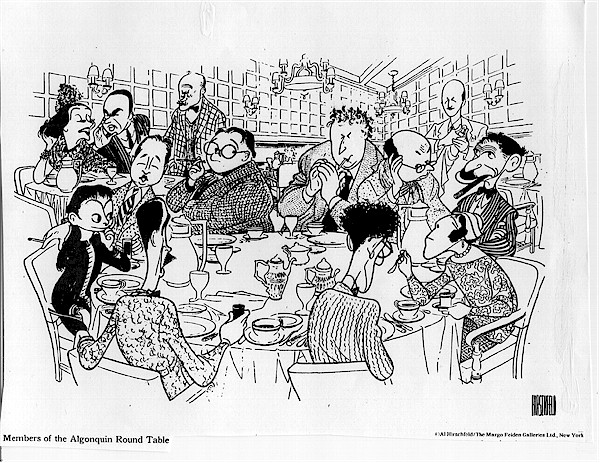

In his excellent blog site, Dayton in Manhattan, Tom Miller writes that the Isaac Brokaw mansion first faced the wrecking ball after Isaac’s eldest son, George, moved out in 1925. George “intensely disliked the house” because of its size and maintenance costs, and petitioned the courts to allow him to mortgage the property for $800,000 and use the money to demolish the mansion and erect a modern apartment house.

His brother, Howard, blocked the move. Three years later, the court ruled that the house could not be sold nor razed without the mutual agreement of all the Brokaw siblings, so George moved back in.

George died seven years later of a heart attack. His wife, Frances Ford Seymour would marry Henry Fonda a year later and have two children, Jane and Peter (George was married twice, the first time to Clare Boothe, who would later become Clare Boothe Luce).

The mansion was then occupied as offices for the Institute of Radio Engineers. When it was announced in 1965 that the mansion (and the adjacent mansions of the Brokaw children) were to be demolished to make way for a high-rise apartment building, there was an outcry from members of the city’s nascent Landmarks Preservation Commission, still stinging from the destruction of Penn Station. Miller writes that demolition workers were paid overtime to begin immediate destruction of the mansions in order to preclude the possibility of a court order to stop the work.

The Yerkes mansion, on the other hand, disappeared rather unceremoniously. According to Miller, a neighbor, Thomas Fortune Ryan, bought the house in 1925 and tore it down in order to enlarge his flower garden. In 1937 an apartment building was erected on the site. I recommend that you check out Miller’s entertaining and informative posts on both the Brokaw and Yerkes mansions.

The Dec. 19 issue also featured a column by Gilbert Seldes titled “Complaint.” Seldes bemoaned the remodeling of “sober, decent” brownstones at Fiftieth Street and beyond (Beekman Place) into overly ornamented facades favored by the Babbitt set:

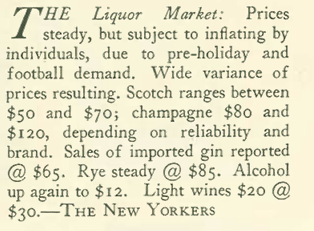

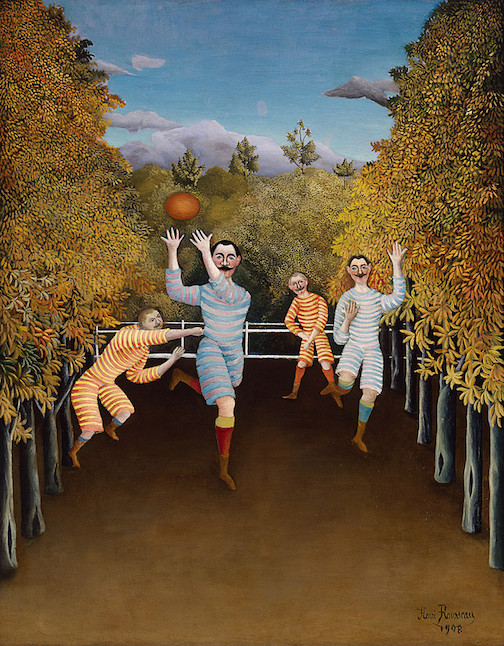

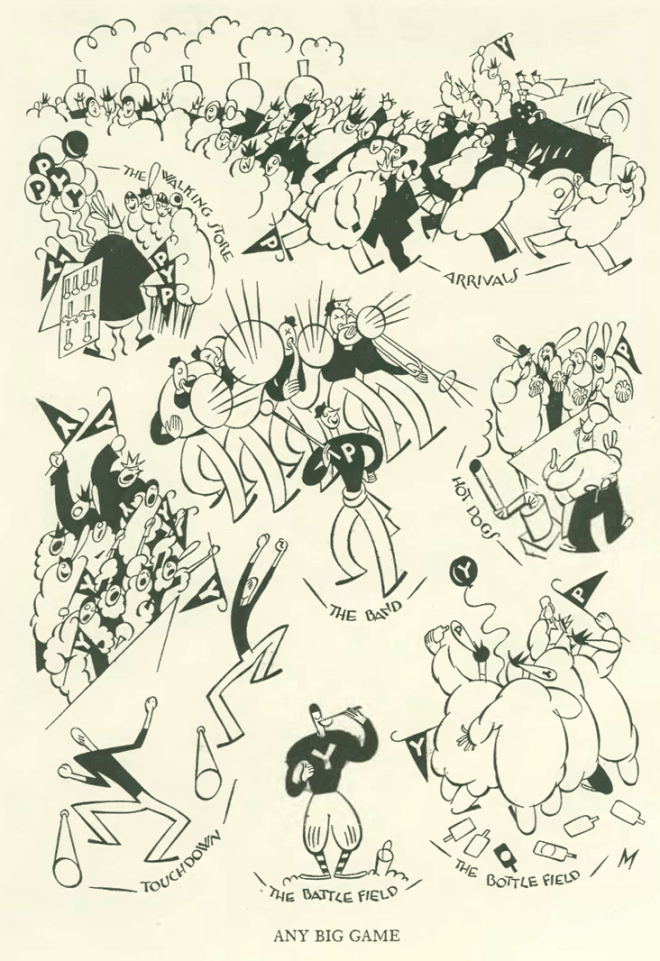

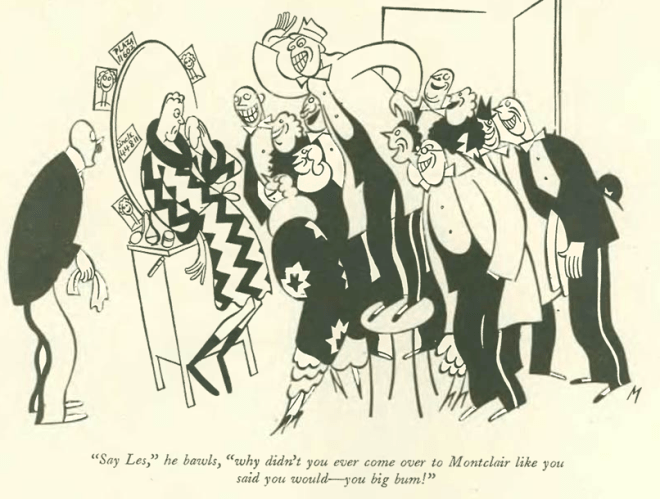

With the much-publicized signing of famed halfback Red Grange to the Chicago Bears (a $100,000 annual contract), the professionalization of football and the money attached to it were frequent topics in the magazine. Howard Brubaker, in “Of All Things,” noted:

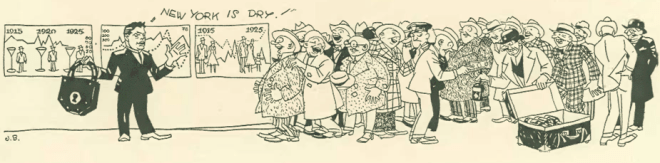

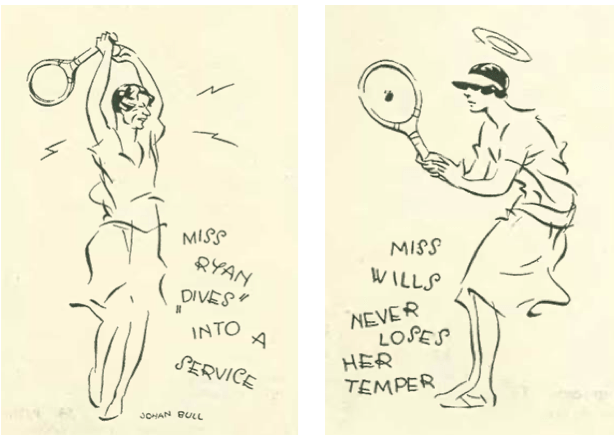

And in this illustration by Johan Bull, Grange is depicted carrying a large money bag at New York’s annual Christmas Bazaar:

“Profiles” looked at the life of pianist and composer Leo Ornstein, noted for performing and composing avant-garde works. Ornstein would have a long career, completing his eighth and final piano sonata at the age of 97. He died in 2002 at age 108.

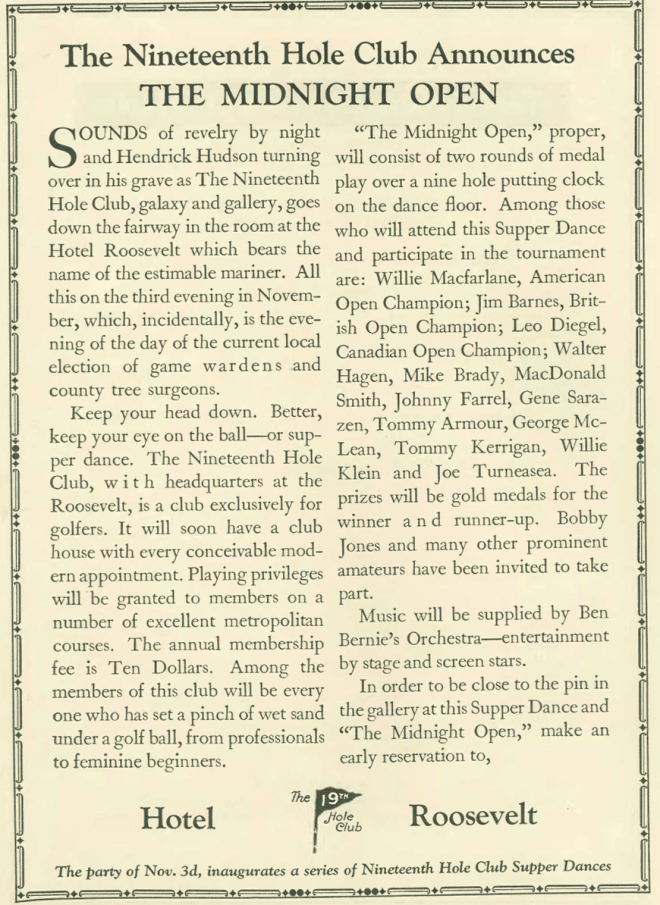

The Marx Brothers’s broadway musical The Cocoanuts wowed audiences (and New Yorker theatre critic Herman J. Mankiewicz) at the Lyric Theatre:

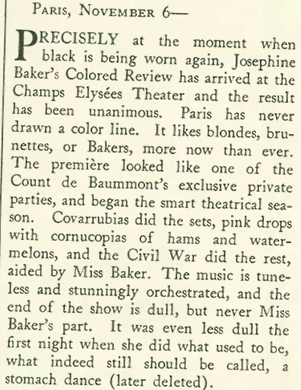

In her Paris Letter, Janet Flanner announced the deaths of “two great servers of the French palate”—Emile Pruinier (famed for his Portuguese oysters) and Mother Soret of Lyons, who “died with a knife in her hand” and whose death was “solemnly listed in Comoedia as that of an artist.”

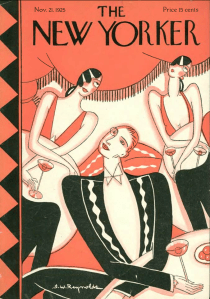

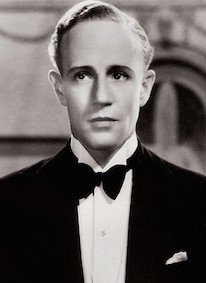

And to stay in the spirit of the holidays, this Christmas advertisement from the back cover:

Next Time: We Ring Out the Year…