Above, left, a 1935 portrait of Gertrude Stein by Carl Van Vechten; right, Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas arriving in New York aboard the French Line’s SS Champlain in 1934. (Library of Congress/AP)

Much of America’s literary world was abuzz about the arrival of Gertrude Stein in New York after her nearly three-decade absence from the States. Audiences were mostly receptive to Stein’s lectures, even if they were largely unintelligible, but The New Yorker would have none of it.

Stein (1874–1946) visited the U.S. at the urging of friends who suggested that a lecture tour might help her gain an American audience for her work. She crisscrossed the country for 191 days, delivering seventy-four lectures in thirty-seven cities.

Writing for the Smithsonian Magazine (October 2011), Senior Editor Megan Gambino notes that publishing houses regarded Stein’s writing style as incomprehensible (Gambino writes that shortly after her arrival in the U.S., “psychiatrists speculated that Stein suffered from palilalia, a speech disorder that causes patients to stutter over words or phrases”), but in 1933 “she at last achieved the mass appeal she desired when she used a clearer, more direct voice” in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. However, Stein was still best known in the U.S. for her “insane” writings, as one New York Times reporter described Stein’s work upon the writer’s arrival in New York. Excerpts from the Oct. 25, 1934 edition of the Times:

Stein had also achieved success in America via her libretto to Virgil Thomson’s opera Four Saints in Three Acts. Prior to her visit, Stein was featured in a newsreel reading the “pigeon” passage from the libretto, which James Thurber satirized in this piece titled “There’s An Owl In My Room.” Excerpts.

Here is a YouTube clip of the newsreel satirized by Thurber. Stein begins her “pigeon” reading at the 30-second mark:

If Thurber found the libretto ridiculous, it was an opinion not necessarily shared by audiences who attended Four Saints in Three Acts, which premiered in Hartford, Connecticut, before making a six-week run on Broadway.

Since Stein had never seen the opera performed, writer and photographer Carl Van Vechten convinced Stein and Toklas to fly on an airplane for the first time in order to be able to see the play in Chicago.

Thurber wasn’t the only New Yorker writer to throw shade on Stein’s visit. In his “Books” column, Clifton Fadiman described Stein as a “mamma of dada” and a “Keyserling in divided skirts” (Hermann Keyserling was a non-academic German philosopher known for his platitudinous, obscure writings). Excerpt:

Fadiman continued by excoriating Stein’s latest book, Portraits and Prayers, likening its “shrill, incantatory” quality to “the rituals of a small child at solitary play.”

* * *

Over the Rainbow

We leave Gertrude Stein for the time being and check in with Lois Long, who was sampling the fall attractions of the New York nightclub scene in “Tables for Two.” In these excerpts, the 32-year-old Long continued her pose as a much older woman (“about to settle down with a gray shawl”) as she bemoaned the bourgeoisie excess of places like the Colony, once known for its boho, speakeasy atmosphere. And then there was the Rainbow Room, with its organ blaring full blast to the delight of gawking tourists.

* * *

From Our Advertisers

Just one ad from the Nov. 17 issue (more to come below)…the latest athlete to attest to the energizing effects of Camel cigarettes…Cliff Montgomery (1910–2005) was famed for a hidden ball trick play that led one of the greatest athletic upsets—Columbia’s 7-0 win over Stanford in the 1934 Rose Bowl. Montgomery would play one year with the NFL Brooklyn Dodgers, and would later earn a Silver Star for his heroism during World War II…

…on to our cartoonists, we begin with Robert Day’s jolly illustration for the “Goings On About Town” section…

…Rea Irvin looked into fair play among the fox hunting set…

…Garrett Price gave us a tender moment among the bones at the American Museum of Natural History…

…and Peter Arno introduced two wrestlers to an unwelcoming hostess…

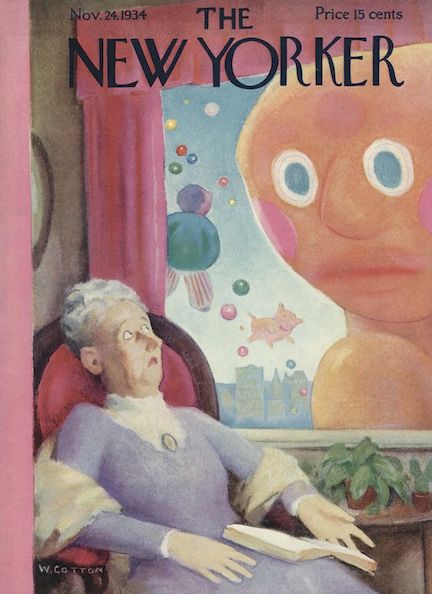

…on to Nov. 24, 1934 issue, and the perils of the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade as illustrated on the cover by William Cotton…

…where we find still more scorn being heaped upon Gertrude Stein. “The Talk of the Town” offered this observation (excerpt):

…and E.B. White had the last word on Stein in his Dec. 1, 1934 “Notes and Comment” column:

* * *

There Goes the Neighborhood

Returning to the Nov. 24 issue, Alberta Williams penned a lengthy “A Reporter at Large” column, titled “White-Collar Neighbors,” about the new Knickerbocker Village development in the Lower East Side. Real estate developer Fred French razed roughly one hundred buildings to build what has since been criticized as an example of early gentrification in Manhattan. Williams assessed the development after more than a year of construction, finding that despite federal funding, the leasing company had yet to rent any apartments “to Negroes or Orientals.” Although the development was meant to serve some of the families it displaced, the vast majority were forced to move back into slums due to escalating rents.

* * *

Dollmaker

Raised in rural Nebraska, at an early age Rose O’Neill (1874–1944) demonstrated an artistic bent, and was already a published illustrator and writer when she drew her first images of “Kewpie” around the year 1908. A German doll manufacturer began producing a doll version of Kewpie in 1913, and they became an immediate hit, making O’Neill a millionaire and for a time the highest-paid female illustrator in the world. When Alexander King penned a profile of O’Neill, Kewpies were no longer the rage, but O’Neill was nevertheless determined to find success in a new doll line. Excerpts:

* * *

Last Call

Lois Long was back with another installment of “Tables for Two” and in these excerpts she found the Central Park Casino a welcome place to hang out, apparently unaware that Parks Commissioner Robert Moses had already served an eviction notice to the Casino’s owners (Moses would tear down the Casino in 1936, mostly to settle a personal vendetta). Long also found respite at the Place Piquale, which featured the musical stylings of Eve Symington.

At the Place Piquale, Long was “grateful” to see that silent film star Louise Brooks was also a good dancer. An icon of Jazz Age flapper culture, Brooks loathed the Hollywood scene and the mediocre roles it offered, and after a stint making films in Europe she returned to the States, appearing in three more films before declaring bankruptcy in 1932. A former dancer for the Ziegfeld Follies, Brooks had turned back to dancing in nightclubs to make a living.

…and dance remains a theme with John Mosher’s film review of the Fred Astaire and Ginger Roger musical The Gay Divorcee, which was based on the 1932 Broadway musical Gay Divorce starring Astaire and Claire Luce.

* * *

Using Her Heads

Clifton Fadiman praised Peggy Bacon’s collection of caricatures, Off With Their Heads!, which included drawings of fellow New Yorker contributors as well as various Algonquin Hotel acolytes. Excerpt:

* * *

More From Our Advertisers

“Beautiful Vanderbilts” Mrs. Reginald Vanderbilt and Miss Frederica Vanderbilt Webb wowed one unnamed dermatologist who discovered that both had 20-year-old skin even though they were seven years apart! “Mrs. Reginald” was Gloria Morgan Vanderbilt, who was thirty when this ad was produced (Miss Frederica was apparently twenty-three). We’ve met Gloria Morgan Vanderbilt before, shilling for Pond’s—she was the maternal grandmother of television journalist Anderson Cooper, and earned her “bad mom” rep from Vanderbilt vs. Whitney, one of America’s most sensational custody trials…

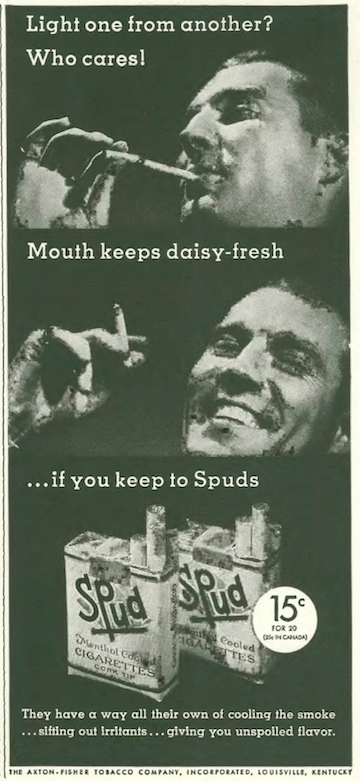

…we move from skin care to who cares…in this case how many Spud cigs you smoke…hell, smoke three packs a day if you like, the cooling menthol will always keep you feeling fresh even as your lungs gradually darken and shrivel up…

…and here’s a lesson from the makers of Inecto hair dye, no doubt a company solely run by men, who schooled wives with the advice that you’d better color that gray hair pronto or your hubby will kick you to the curb…

…the New York American was a Hearst broadsheet known for its sensationalism, however it did claim Damon Runyon, Alice Hughes, Robert Benchley and Frank Sullivan among its contributors…the morning American merged with the New York Evening Journal to form the American and Evening Journal in 1937. That paper folded in 1966…

…illustrator Stuart Hay drew up this full page ad for the makers of Beech-Nut candy and chewing gum…when I was a kid we used to call this “grandpa gum”…

…on to our cartoonists, we begin with a Thanksgiving spot by Alain (Daniel Brustlein)…

…Barbara Shermund delivered another life of the party…

…George Price was finally bringing his floating man back to earth…

…Otto Soglow gave us an unlikely detour…

…Gardner Rea signaled the end to the 1933-34 Chicago World’s Fair…with a boom…

…Leonard Dove dialed up a familiar trope…

…and we close on a more pious note, with Mary Petty…

Next Time: Al’s Menagerie…