“The Talk of the Town” welcomed midsummer by noting the changes in the “new Summer Social Register…A long, slow swing of the same pendulum-like power which shifts the vogue in night clubs and restaurants is the migration to inland resorts…The Hamptons have fallen off, Newport has weakened and of the coasts only New England, boasting ‘the prestige of the Summer White House,’ has held its own.”

It was thought that perhaps financial pressures on waterfront acreage “had added zeros to the 400” and “The fragments of our battered conservatives turn and twist uneasily, seeking readjustment, new barriers (translation: old money responds to the invasion of new money).

This siege on the sanctity of “the 400” – a reference to the number limited to Mrs. John Jacob Astor’s social circle – included the appearance of “scanty” bathing suits on Southampton beaches:

Corroborative evidence of the storming of the conservative fortresses by Undesirables comes with Southampton’s latest protest against scanty bathing costumes, “usually worn by strangers.”

Corroborative evidence of the storming of the conservative fortresses by Undesirables comes with Southampton’s latest protest against scanty bathing costumes, “usually worn by strangers.”

Just what these costumes were or were not, the Southampton Bathing Corporation did not say, but they ruled that stockings and cape must be worn “while walking down to the water.” This ordinance to apply “especially at week-ends and during tennis week.

Beginning with this issue, the “When Nights Are Bold” feature was passed from Charles Baskerville (pen name “Top Hat”) to the newly hired Lois Long (pen name “Lipstick”). In her first column for The New Yorker, Long suggested that for those “who can get out of town at will,” the Arrowhead Inn “up Riverdale way” and high on a bluff above the Hudson, was a popular destination for dining and dancing, even if the dancing crowd left something to be desired:

Another recommended Hudson River location was the Claremont (but alas, no dancing!), while for those staying in the city, Long recommended the Embassy Club at 695 Fifth Avenue.

According to Here At The New Yorker by Brendan Gill, Long chronicled nightly escapades of drinking, dining, and dancing for The New Yorker, and because her readers did not know who she was, she often jested in her columns about being a “short squat maiden of forty” or a “kindly, old, bearded gentleman.” However, in the announcement of her marriage to The New Yorker cartoonist Peter Arno, she revealed her true identity.

Harold Ross hired Long in the summer of 1925 as part of a group of “saviors” he hoped would help boost his struggling magazine. The group included Arno, Katharine Angell, managing editor Ralph Ingersoll, and cartoonist Helen Hokinson.

Although she was a favorite of Ross’s, the two couldn’t be more different, as historian Joshua Zeitz explains in Flapper: A Madcap Story of Sex, Style, Celebrity, and the Women Who Made America Modern (2006), Long knew just how to embarrass the girl-shy editor, and loved to do it:

(Ross) was a staid and proper Midwesterner, and she was absolutely a wild woman. She would come into the office at four in the morning, usually inebriated, still in an evening dress and she would, having forgotten the key to her cubicle, she would normally prop herself up on a chair and try to, you know, in stocking feet, jump over the cubicle usually in a dress that was too immodest for Harold Ross’ liking. She was in every sense of the word, both in public and private, the embodiment of the 1920s flapper. And her readers really loved her.

“Talk” also reported that Mrs. (Julia Lydig) Hoyt had “very nearly arrived,” and was capitalizing on her stage career through endorsements for cold creams and articles on social etiquette. “The motion picture industry and stage know her and now she is a designer at highest salary ever paid to an American.”

Prohibition continued to dampen the spirits (pun intended) of New Yorkers, particularly during the summer season. The editors noted that of 36 random summer reminiscences submitted to the magazine, eighteen were “direct references to alcoholic concoctions and all but a few theatrical recollections directly suggested indulgence. Then the editors offered their own wistful recollections:

Of course we remember “The Doctor’s cocktails” mixed by the “Commissioner” at the Astor…the highball sign at Forty-second and Broadway…the “Old Virginia Mountain” between the acts under the smile of Old King Cole…the Sunday afternoon absinthe drips at the Lafayette…Champagne at the Claremont on a June night…the Manhattan bar at cocktail time…the Ancient and Honorables in the Buckingham bar….the Navy in mufti at Shanley’s…the horseshoe bar at the Waldorf…the blue dawn of the West Forties…

Of course…but why bring that up again? It’s merely driving us down the street to that place that gave us the card last week and the rumor has just reached us that they are back serving Scotch in teacups, accompanied by a large earthenware teapot filled with soda.

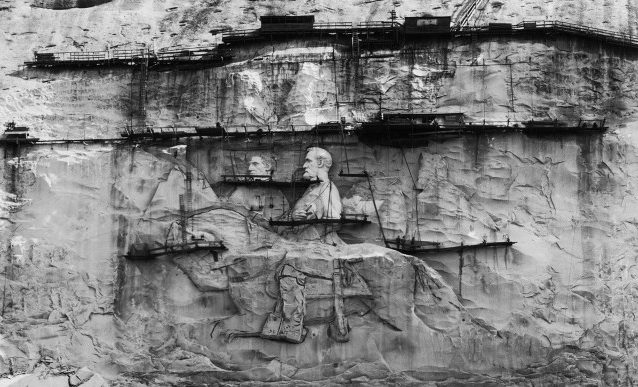

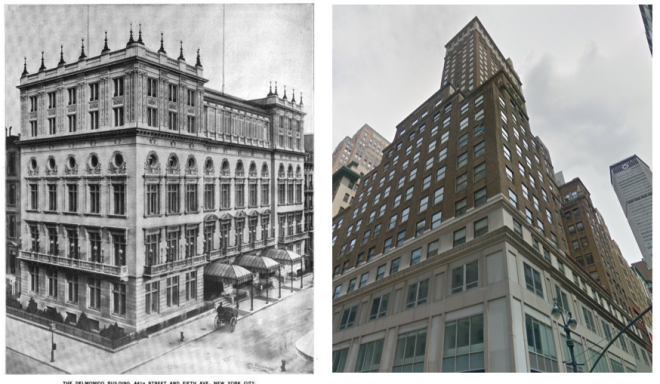

Also lamented was the loss of renown restaurant Delmonico’s, which had been closed for some time (due mostly to alcohol sales lost to Prohibition; its famous rival across the street, Sherry’s, closed in 1919 for the same reason) but was now yielding to the wrecking ball: “Possibly, Delmonico’s might have been saved as a tradition, but finances and the changes of Fifth Avenue’s complexion forbade…Now we are to see yet another skyscraper, this one on the site where once they dined; where once they danced; across the street from old Sherry’s, long since a bank; orchestraed only by adding machines.”

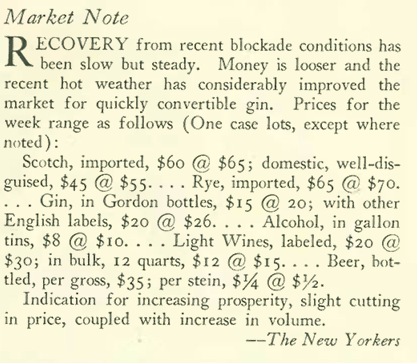

“The Talk of the Town” concluded with a price list for various bootleg spirits, a feature that would continue through the Prohibition:

Fresh off his dismantling of those clod-kickers in Chicago, Ben Hecht continued his dyspeptic tirade on the America that lay beyond Gotham, specifically attacking its love of the “Pollyanna twaddle flow” of entertainment from Hollywood:

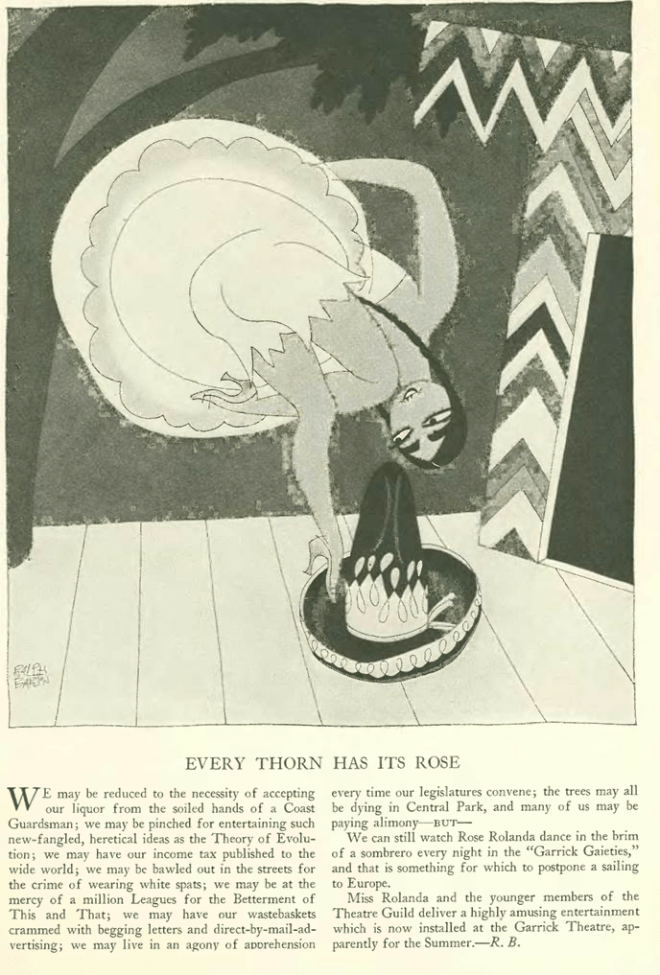

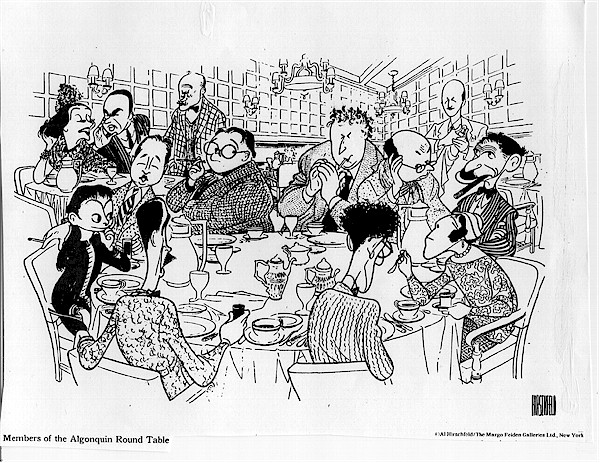

Ralph Barton, on the other hand, offered of a view of the entire earth, from the vantage point of a Martian observer:

In “Profiles,” Waldo Frank (writing under the pen-name “Searchlight”) looked askance at the life and work of writer Sinclair Lewis.

Frank offered these observations: “Once upon a time, America created a man-child in her own image…

Frank offered these observations: “Once upon a time, America created a man-child in her own image…

There’s a strange thing about America. She is passionately in love with herself, and is ashamed of herself…Here was a dilemma, Could not her self be served up to America in such a way that she could love herself—and save her shame? Sinclair Lewis, true American son, was elect to solve it.”

And for those rising young men who did not wish to mix with the unwashed during the summer social season, membership to the Allerton Club Residences was recommended in this back page advertisement:

And yes, the Scopes Monkey Trial is still on the minds of the editors:

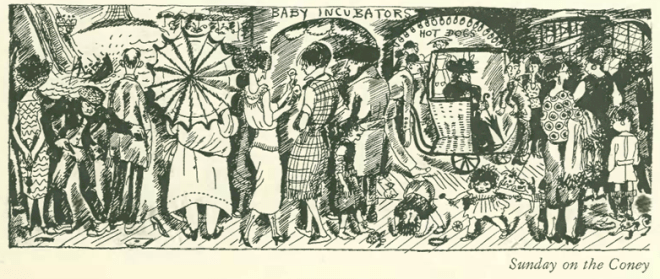

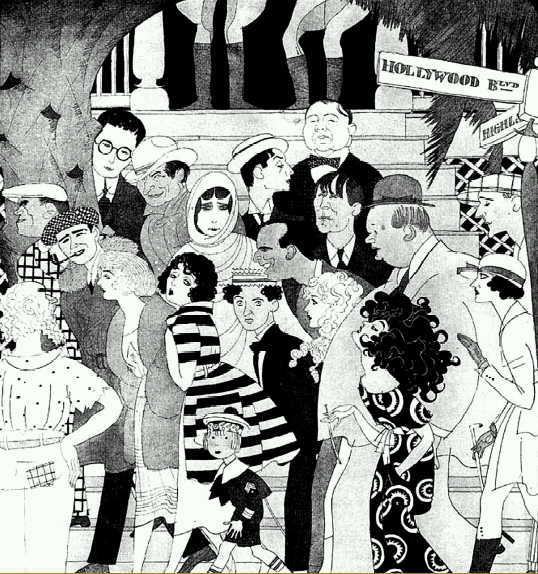

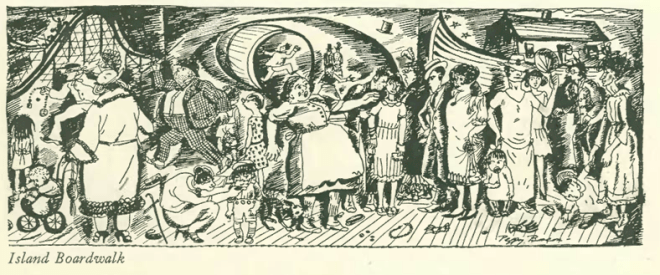

And finally, to close out with a beach theme, a two-page illustration from “The Talk of the Town” section, an early work by illustrator Peggy Bacon:

Next time, lots of horseplay: