“The maddest week any of us remembers in the theatre,” observed “The Talk of the Town” for Sept. 26, 1925, as The Green Hat (the play based on Michael Arlen’s popular novel) was creating a riotous rush for tickets on The Great White Way.

Talk described The Green Hat as “a play so eagerly sought after that even in a week providing 12 openings, speculators were offering five hundred dollars for twenty tickets” ($500 then is roughly equivalent to $6,800 today).

It was noted that despite the openings of such plays as The Vortex and No, No Nanette, The Green Hat was consuming most of the attention, with the opening attracting “every bigwig of Broadway” including Irving Berlin.

One notable guest, however, did not arrive until after the second act: Michael Arlen himself. It was said that Arlen had never seen a complete performance of his play, due to “nervousness.”

Perhaps there was a good reason for his butterflies.

Later in the “Critique” section, Herman J. Mankiewicz (H.J.M.) pronounced The Green Hat as “unreal and consequently uninteresting…a grand sentimental debauch for the romantically inclined. It has no place at all in the discussion of the Higher Theatre…”

Mankiewicz observed that the acting itself was passable, with Katherine Cornell delivering an “excellent, though scarcely ideal portrayal of Iris March,” but she was “showing the strains of playing a role that has no more grasp on life than a little boy’s daydream that the Giants will, after all, snatch the pennant from Pittsburgh.”

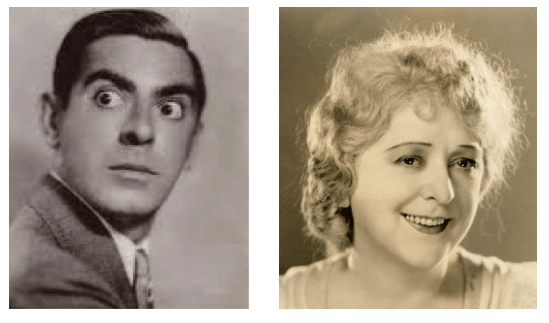

A publicity photo from the play:

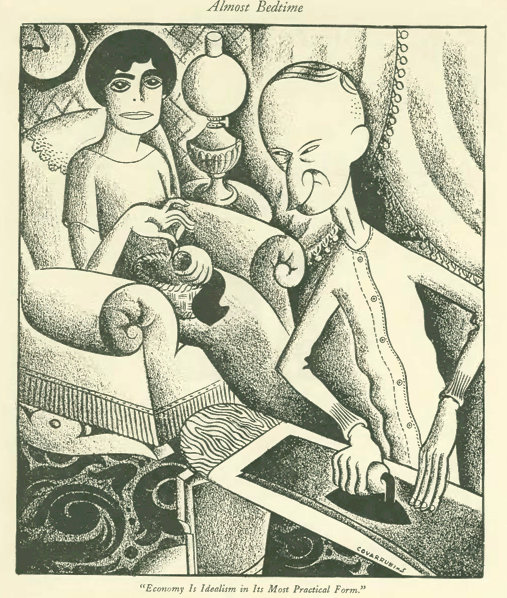

And Ralph Barton’s unique take on the whole thing:

Mankiewicz also reviewed the play, Arms and the Man, but his focus was not the play but rather an annoying patron in seat T-112:

Although the Scopes Trial was long over, The New Yorker still found opportunities to take potshots at the backwardness and Babbittry of folks in the hinterlands:

Talk also continued to help its readers with regular updates on the bootleg liquor trade:

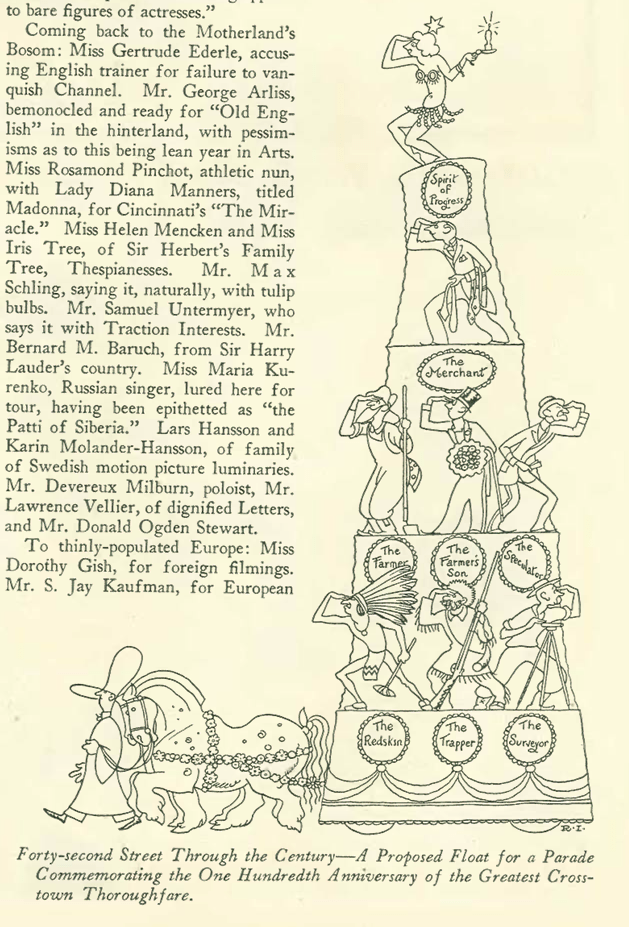

An article titled “Mid-Town” celebrated the 100th anniversary of 42nd Street. Henry Collins Brown wrote that 100 years had changed the street “from a dusty country lane to a self-contained metropolis. The brownstone of its middle age has given way to granite and marble. It has seen a railroad dynasty rise and has written its epitaph on a narrow, short avenue.”

Then Brown concluded with these prescient thoughts:

An illustrated tribute (by Rea Irvin) to 42nd Street appeared in the “Talk” section:

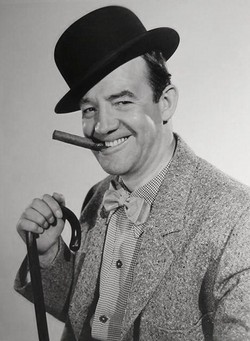

In “Profiles,” Jo Swerling looked at the life of comedian Louis Josephs, known to all as Joe Frisco, a mainstay on the vaudeville circuit in the 1920s and 1930s.

Swerling wrote admiringly that Frisco—who was from Dubuque, Iowa, of all places—was “the comedian’s comic.”

Considered one of the fastest wits in the history of comedy, Frisco was a famous stutterer but could recite his scripted dialogue unimpaired. According to Wikipedia, he was first known for his popular jazz dance act–called by some the “Jewish Charleston”– which was a choreographed series of shuffles, camel walks and turns. He usually danced in a derby hat with a king-sized cigar in his mouth, often performing in front of beautiful women “smoking” prop cigars.

His most famous line was uttered while in a New York hotel. A clerk learned that Frisco had a guest in a room that was only reserved for one occupant, so he called up to the room and said, “Mr. Frisco, we understand you have a young lady in your room.” Frisco replied, “T-t-t-then send up another G-g-gideon B-b-bible, please.”

With vaudeville in decline, in the 1940s Frisco moved to Hollywood and appeared in several low-budget movies. A compulsive gambler who was constantly in debt, he died penniless in Los Angeles in 1958.

In “Motion Pictures,” Harold Lloyd’s “college comedy,” The Freshman, which Theodore Shane wrote was filled with “glorious laughter.” Shane also noted that another Rin Tin Tin picture was appearing at Warner’s Theatre (Below the Line), and “as usual our hound hero is enlisted on the side of virtue.”

An interesting ad near the back of the magazine (and the book reviews) offered readers an opportunity to sample a new, unnamed work by James Joyce:

What this ad described was an avant-garde work by Joyce that would appear in serialized form until it was finally published in its entirety in 1939 as Finnegans Wake.

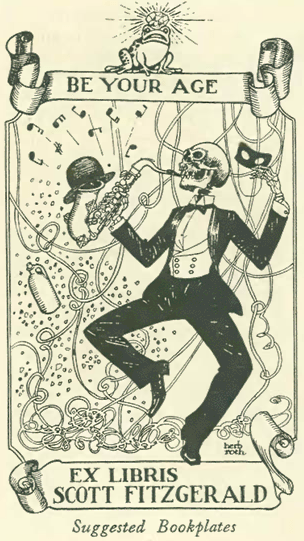

In other book-related matters, this illustration by Herb Roth appeared in the pages of the “Critique” section:

Anne Margaret Daniel wrote about this “Suggested Bookplate” in her May 1, 2013 blog for the Huffington Post, and made this observation:

“Be Your Age” shows how fully the magazine at the pulse of the Jazz Age registered both Fitzgerald’s personification of the decade, in many readers’ eyes, as well as the dangers he had foretold in The Beautiful and Damned, and again in Gatsby of decadence and of the coming Crash. It’s a very double-edged image of festivity and fatality, just like so many of the images of people at parties that end in disasters in Fitzgerald’s best-known, and best-loved, novel.

Charles Baskerville (Top Hat) continued to report from the City of Lights in his “Paris Letter,” mainly focusing on the doings of American tourists. No offense to the urbane and talented Baskerville (also a great illustrator), but I am looking forward to Janet Flanner’s (a.k.a. Genêt) take on Paris in future issues (Does anyone out there know if she wrote the unsigned “Paris Letter” in the Sept. 5 issue?).

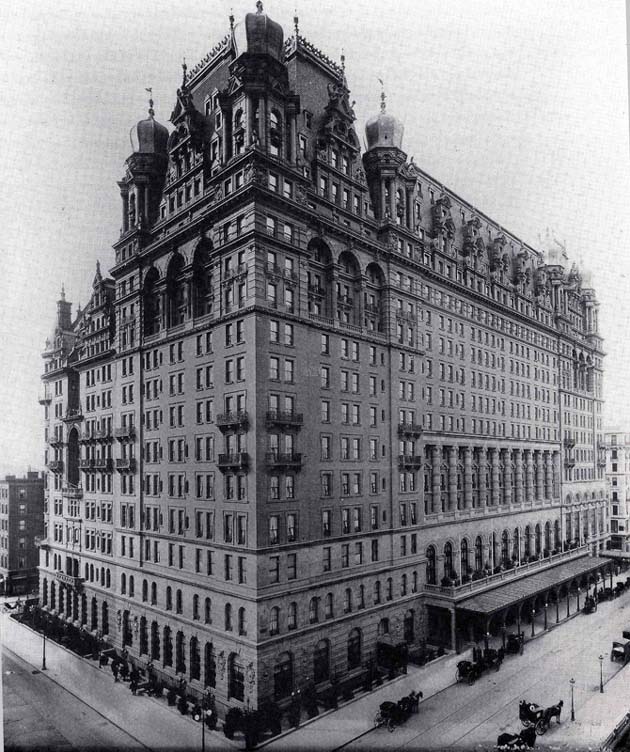

The issue featured a rather faded-looking movie ad for the back cover:

And a still from the film on which the drawing is no doubt based:

Next Time: Lois Long’s Fifth Avenue…