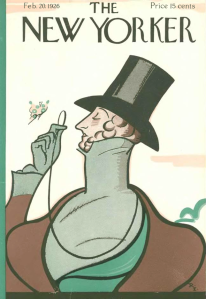

In reading all of these past issues of The New Yorker (a year’s worth, as of this post) one writer in particular jumps from the pages: Lois Long.

Perhaps it was her irreverent, high-spirited style and her fearless forays into any topic. She was the most modern of the New Yorker writers, developing a style that communicated directly to the reader as a confidant.

Her output was also impressive, writing about nightlife in “Tables for Two” under the pseudonym “Lipstick” and also about fashion in “One and Off the Avenue.” In his autobiography, Point of Departure, colleague Ralph Ingersoll wrote that Long “did a wheel-horse job of pulling The New Yorker through its first years,” with an “almost infinite capacity for being childishly delighted” while also possessing a “native shrewdness, an ability to keep her head.”

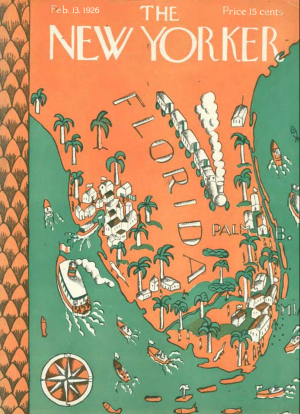

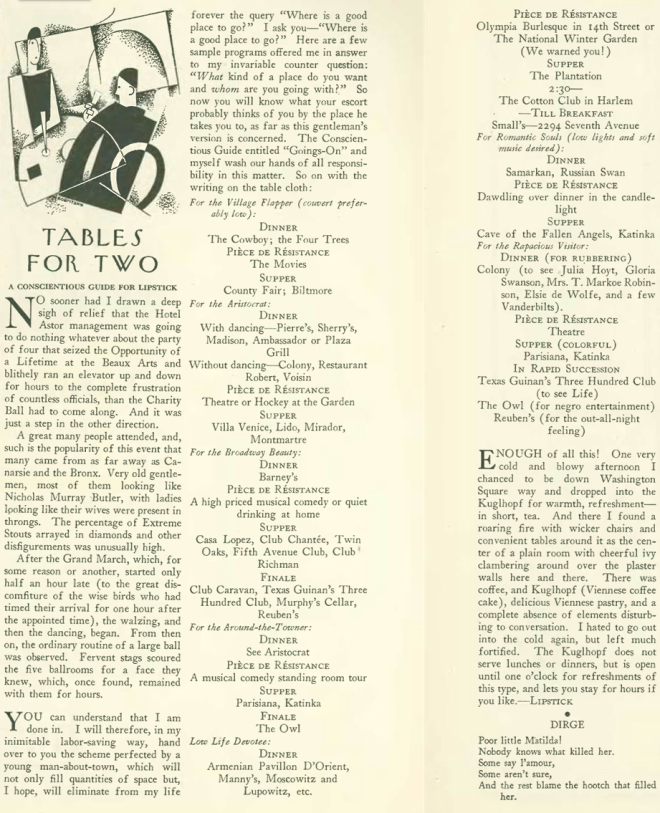

Long was in rare form in the Feb. 13, 1926 issue, offering a comprehensive list of evening entertainments for everyone from a flapper to an aristocrat. Here’s the entire column:

According to Long, if you were an aristocrat, or a “rapacious visitor” wishing to rubberneck at the rich and famous, The Colony restaurant was a good choice for the dinner hour.

The Colony, which began as a speakeasy in the early 1920s, was one of the places to be seen in New York for many decades. According to the blog Lost Past Remembered, “there was a Colony ‘crowd’ that included Hollywood royalty Errol Flynn, Gary Cooper, and Joan Crawford as well as the real deal ––The Duke and Duchess of Windsor were great fans (as were assorted bankers, brokers, wheeler dealers and gangsters and socialites).”

In those days you could display your status by where you were seated at The Colony. In later years the place was frequented by the likes of Jackie O and her sister Lee Radziwill. Writer Truman Capote, who enjoyed a special back table under a TV set, reportedly wept when the restaurant closed in 1971.

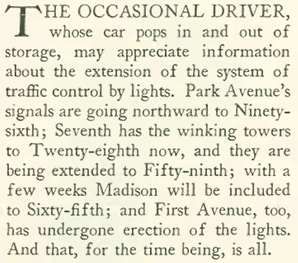

On to a less glamorous subject, “The Talk of the Town” made note of the extension of traffic lights in the city:

In 1926 traffic lights were still something of a novelty in New York, which didn’t install its first traffic light until 1920.

According to the New York Times (May 16, 2014), the first permanent traffic lights in New York went up in 1920, a gift from millionaire physician Dr. John A. Harriss who was fascinated by street conditions. His design “was a homely wooden shed on a latticework of steel, from which a police officer changed signals, allowing one to two minutes for each direction. Although the meanings we attach to red and green now seem like the natural order of things, in 1920 green meant Fifth Avenue traffic was to stop so crosstown traffic could proceed; white meant go. Most crosstown streets and Fifth Avenue were still two-way.”

The signals were so popular that in 1922 “the Fifth Avenue Association gave the city, at a cost of $126,000, a new set of signals, seven ornate bronze 23-foot-high towers (designed by Joseph H. Freedlander) placed at intersections along Fifth from 14th to 57th Streets.”

Within a few years it was determined that the towers were blocking the roadway, so in 1929 Freedlander was “called back to design a new two-light traffic signal, also bronze, to be placed on the corners. These were topped by statues of Mercury and lasted until 1964. A few of the Mercury statues have survived, but Freedlander’s 1922 towers have completely vanished.”

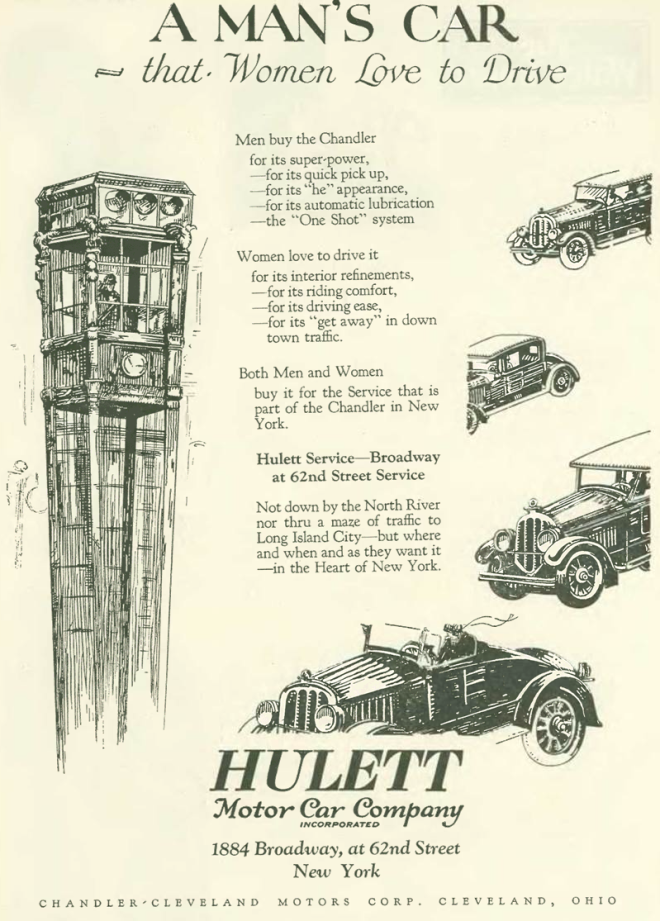

Skipping ahead a few issues, this Hulett advertisement from the March 20, 1926 issue features a drawing of the Freelander signal:

* * *

Although F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel The Great Gatsby received a brief, dismissive review from the magazine in 1925, a stage adaptation of the novel was received favorably by theatre critic Gilbert W. Gabriel:

In the movies, critic Theodore Shane gushed over a new film by Robert Flaherty, famed director of Nanook of the North. This time around Flaherty turned his lens on a Polynesian paradise in Moana:

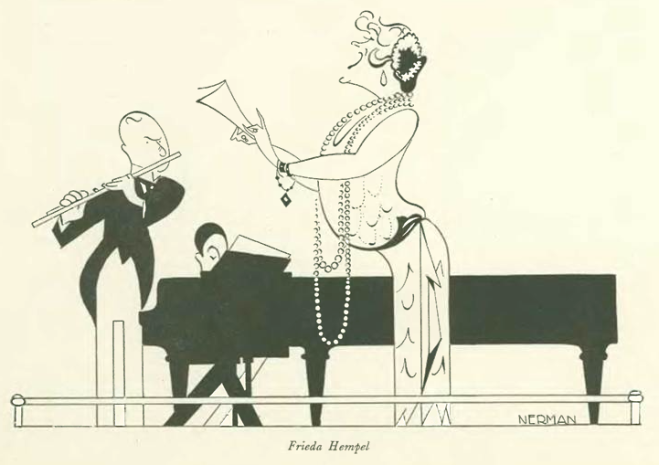

And to wrap things up, a drawing by Einer Nerman of German soprano Frieda Hempel…

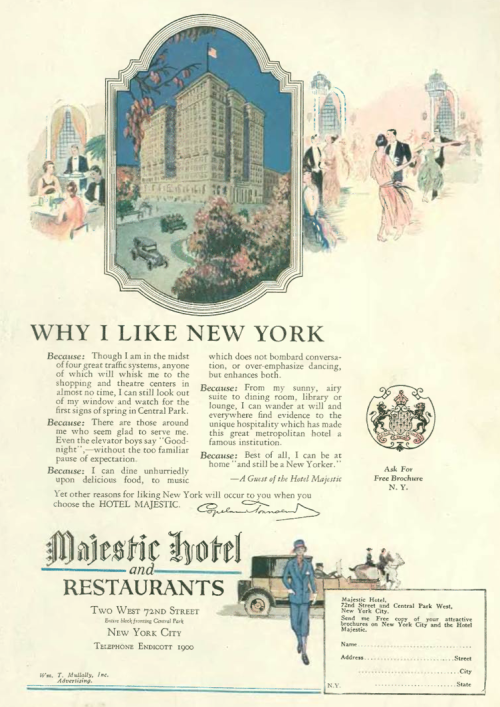

And this advertisement exhorting readers to stay at the Hotel Majestic. The hotel, built in 1894, would fall to a wrecking ball in 1929, just three years after this ad appeared:

Next Time: The Magazine Marks One Year…

This makes me want to go back in time and be a flapper for a night! But just one night because I really like jeans and t-shirts!

LikeLike